277: Apology

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

My mom was a therapist and she saw hundreds of couples where somebody in the couple had cheated. And then the couple tried to stay together and work it out, and that's how they ended up in couples counseling. And my mom said this thing nearly always happens in this situation. This thing happens where the person who cheated confesses. Tells the spouse as many details as the spouse wants to hear, which usually is a lot. And in fact, you kind of have to tell them everything they want if there's going to be any kind of forgiveness. And so it's just all this painful detail. What happened this particular day when you said you were here and did you say I love you to the other person? Just like the incredibly painful, incredibly hard stuff. And the person who cheated says that they know they were in the wrong, and they want to work it out, and they're sorry. They're so, so sorry.

And then weeks pass, and everybody tries to get along. And at some point, the person who cheated starts to feel a little better. You know, they confessed. They cleared the air. It's a new beginning. But their spouse is living still, in a world of pain. The spouse doesn't trust them. The betrayal was so huge, the lies were so big, the spouse is still wary. And still, little bursts of anger. They're not over it.

And here's where it gets complicated. The person who cheated starts to get impatient. They feel like, come on, I confessed. I said I'm sorry. I've done everything I can do to make this right. But you just won't let it go. And the other person can't let it go. A very hard thing for both of them. A very hard thing for any couple to get through. And it almost always happens. The apology wasn't enough. And really, there are so many situations where apologizing doesn't do the trick, where it doesn't satisfy both parties. And not just big situations, these can be the tiniest situations in the world.

Sarah Vowell, one of our contributing editors on the radio show says that she was running late on her way to meet a friend for breakfast.

Sarah Vowell

I was on the subway and I realized I didn't know where breakfast was. I was, I don't know, 15 or 20 minutes late, which was just the most agonizing 15 minutes of my life of me running up and down 9th Avenue trying to remember where I was supposed to meet him. You know, I got there and he had wondered where was I was, but he brought the paper and he was fine, so I spent the entire breakfast apologizing. Then when I got home I sent him an email apologizing. Then before I went to bed I sent another apology email.

Then the next time we had breakfast I was 15 minutes early and then had to talk about how I was early this time. And it's just so stupid. And I realized at that point, the apology sickness becomes a kind of narcissism. Like, all you think about is yourself and you feel like, oh, my actions affected this other person so much I need to just constantly apologize. When really, it wasn't that big of a deal.

Ira Glass

This happens all the time. The apology can go wrong for either person in the transaction. Even the apologizer.

Sarah Vowell

I feel like he totally accepted my apology. It's more like I didn't accept my apology. [LAUGHTER]

Ira Glass

There's moments where you apologize to somebody and you're not doing it for selfish reasons, but because you really want them to know you're sorry. And where they really hear what you're saying and your eyes lock and everybody knows that it happened, the apology happened. Those are almost pretty rare, I think.

Today on our radio show, we have three stories of people groping their way toward I'm sorry, toward this moment of apology. From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life distributed by Public Radio International, I'm Ira Glass.

Our program today in three acts. And let me just say right here, it's a politics free program. Let's have a little break. Act one, "Repeat After Me." In that story, David Sedaris, his sister, and a talking bird. Act two, "Dial S for Sorry." In which we have a little visit with Mr. Apology and his wife. Act three, "Two Words You Never Want to Hear From Your Doctor." In that act, a movement to try to get people who do not like to say they're wrong to say they're wrong. Stay with us.

Act One: Repeat After Me

Ira Glass

Act one, "Repeat After Me."

This story was recorded in front of a live audience. Here's David Sedaris.

David Sedaris

Although we discussed my upcoming visit to Winston-Salem, my sister and I didn't make exact arrangements until the eve of my arrival when I phoned from a hotel in Salt Lake City.

"I'll be at work when you arrive," she said. "So I'm thinking I'll just leave the key under the ower-ot near the ack door."

The what?

"Ower-ot."

I thought she maybe had something in her mouth until I realized she was speaking in code.

What are you on a speaker phone at a methadone clinic? Why can't you just tell me where you put the god damn house key?

Her voice dropped to a whisper. "I just don't know that I trust these things."

Are you on a cellphone?

"Of course not," she said. "This is just a regular cordless. But still, you have to be careful."

My sister's the type who religiously watches the fear segments of her local eyewitness news broadcasts. Retaining nothing but the headline. She remembers that applesauce can kill you, but forgets that in order to die you have to inject it directly into your bloodstream.

Announcements that cellphone conversations may be picked up by strangers mixed with the reported rise of both home burglaries and brain tumors, meaning that as far as she's concerned all telecommunication is potentially life threatening.

OK, I said. But can you tell me which ower-ot?

"It's ed." She told me. "Well, edish."

I arrived at Lisa's house late the following afternoon, found the key beneath the flower pot, and let myself in through the back door. A lengthy note on the coffee table explained how I might go about operating everything from the television to the waffle iron. Each carefully detailed procedure ending with the line, remember to unplug after use. The note reflected a growing hysteria. Its subtext shrieking, oh my God, he's going to be alone in my house for close to an hour.

She left her work number, her husband's work number, and the number of the next door neighbor, explaining that she didn't know the woman very well, so I probably shouldn't bother her unless it was an emergency. PPS, she's a Baptist, so don't tell her you're gay.

The last time I was alone at my sister's place, she was living in a white brick apartment complex occupied by widows and single middle-aged working women. College hadn't quite worked out the way she'd expected. And after two years in Virginia, she'd returned to Raleigh and taken a job at a wine shop. It was a normal enough life for a 21 year old, but being a dropout was now what she had planned for herself. Worse than that, it had not been planned for her.

As children, we'd been assigned certain roles-- leader, bum, troublemaker, slut. Titles that effectively told us who we were. As the oldest, smartest, and bossiest, it was naturally assumed that Lisa would shoot to the top of her field, earning a master's degree in manipulation, and eventually taking over a medium-sized country. We'd always known her as an authority figure, and while we took a certain joy in watching her fall, it was disorienting to see her with so little confidence.

Suddenly she was relying on other people's opinions, following their advice, and withering at the slightest criticism. Do you really think so? Really? She was putty.

My sister needed patience and understanding, but more often than not, I found myself wanting to shake her. If the oldest wasn't who she was supposed to be, then what did it mean for the rest of us?

Lisa has been marked most likely to succeed and so it confused her to be ringing up gallon jugs of hardy burgundy. I had been branded as lazy and irresponsible, and so it felt right when I, too, dropped out of college.

I went to live with Lisa in her white brick complex. And when I eventually left her with a broken stereo and an unpaid $80 phone bill, the general consensus was, well, what did you expect? I might reinvent myself to strangers, but to this day, as far as my family is concerned, I'm still the one most likely to set your house on fire.

While I accepted my lowered expectations, Lisa fought hard to regain her former title. The wine shop was just a temporary setback and she left shortly after becoming the manager. Photography interested her and so she taught herself to use a camera. Ultimately, landing a job in the photo department of a large international drug company where she took pictures of germs, viruses, and people reacting to germs and viruses.

On weekends, for extra money, she photographed weddings, which really weren't that much of a stretch.

She got married herself and then quit the drug company in order to earn an English degree. When told there was very little call for 30 page essays on Jane Austen, she got a real estate license.

When told the housing market was down, she returned to school to study plants. Her husband, Bob, got a new job in Winston-Salem and so they moved, buying a new three-story home in a quiet, suburban neighborhood.

It was strange to think of my sister living in such a grownup place, and I was relieved to find that neither she nor Bob particularly cared for it. My sister's home didn't really lend itself to snooping and so I spent my hour in the kitchen making small talk with Henry. It was the same conversation we'd had the last time I saw him, yet still I found it fascinating. He asked how I was doing. I said I was all right.

And then as if something might have drastically changed over the last few seconds, he asked again. Of all the elements of my sister's adult life, the house, the husband, the sudden interest in plants, the most unsettling is Henry. Technically, he's a Blue-fronted Amazon. But to the average layman, he's just a big parrot. The type you might see on the shoulder of a pirate.

How you doing? The third time he asked, it sounded as if he really cared. I approached his cage with a detailed answer and when he lunged for the bars I screamed like a girl and ran out of the room.

"Henry likes you," sister said a short while later. She just returned from her job at the plant nursery and was sitting at the table unlacing her sneakers. "See the way he's fanning his tail, he'd never do that for Bob. Would you, Henry?"

Bob had returned from work a few minutes earlier and immediately headed upstairs to spend time with his own bird, a balding, Green-cheeked Conure named Jose.

I thought the two of them might enjoy an occasional conversation, but it turns out they can't stand one another.

"Don't even mention Jose in front of Henry," Lisa said. Bob's birds squawked from the upstairs study and the parrot responded with a series of high piercing barks. It was a trick he'd picked up from Lisa's border collie, Jessie. And what was disturbing was that he sounded exactly like a dog. Just as when speaking English, he sounded exactly like Lisa. It was creepy to hear my sister's voice coming from a beak. But I couldn't say it didn't please me.

"Who's hungry?" she asked. "Who's hungry?" the voice repeated.

I raised my hand and she offered Henry a peanut. Taking it in his claw, his belly sagging almost to the perch, I could understand what someone might see in a parrot. Here was this strange little fat man living in my sister's kitchen. A sympathetic listener turning again and again to ask, so really, how are you?

I'd asked her the same question and she'd said, oh, fine. You know. She's afraid to tell me anything important knowing I'll only turn around and write about it.

In my mind, I'm like a friendly junk man building things from the little pieces of scrap I find here and there. But my family started to see things differently. Their personal lives are the so-called pieces of scrap I so casually pick up. And they're sick of it.

Conversations now start with the words, you have to swear you will never repeat this. I always promise, but it's generally understood that my word is no better than Henry's.

I'd gone to Winston-Salem to address the students at a local college, and then again to break some news. Sometimes when you're stoned it's fun to sit around and think of who might play you in the movie version of your life. What makes it fun is that no one is actually going to make a movie of your life. Lisa and I no longer get stoned and so it was all the harder to announce that my book had been optioned. Meaning that, in fact, someone was going to make a movie of our lives. Not a student, but a real live director people had heard of.

"A what?"

I explained that he was Chinese and she asked if the movie would be in Chinese.

"No," I said, "he lives in America. In California. He's been here since he was a baby."

"So now we have to be in a movie?" She picked her sneakers off the floor and tossed them into the laundry room. "Well," she said, "I can tell you right now that you are not dragging my bird into this."

Once, at a dinner party, I met a woman whose parrot had learned to imitate the automatic ice maker on her new refrigerator. "That's what happens when they're left alone," she'd said.

It was the most depressing bit of information I'd heard in quite a while. And it stuck with me for weeks. Here was this creature born to mock its jungle neighbors and it wound up doing impressions of man-made kitchen appliances.

I repeated this story to Lisa who told me that neglect had nothing to do with it. She then prepared a cappuccino, setting the stage for Henry's pitch perfect imitation of the milk steamer.

He can do the blender too, she said. She opened the cage door and as we sat down to our coffees, Henry glided down under onto the table. "Who wants a kiss?"

She stuck out her tongue and he accepted the tip gingerly between his upper and lower beak. I'd never dream of doing such a thing. Not because it's across the board disgusting, but because he would have bitten the [BLEEP] out of me.

While Henry might occasionally have fanned his tail in my direction, it was understood that he was loyal to only one person. Which, I think, is another reason my sister was so fond of him.

"Was that a good kiss?" she asked. "Did you like that?"

I expected a yes or no answer and was disappointed when he responded with the exact same question, "did you like that?"

Yes, parrots can talk, but unfortunately they have no idea what they're actually saying. When she first got him, Henry spoke the Spanish he'd learned from his captors. When our mother died, Henry learned how to cry. He and Lisa would set each other off and the two of them would go on for hours.

A few years later, in the midst of a brief academic setback, she trained him to act as her emotional cheerleader. I'd call and hear him in the background screaming, "we love you, Lisa!" "And you can do it!"

This was replaced, in time, with the far more practical, where are my keys?

After finishing our coffees, Lisa drove me to Greensboro where I delivered my scheduled lecture. This is to say that I read stories about my family. After the reading I answered questions about them, thinking all the while how odd it was that these strangers seemed to know so much about my brother and sisters.

In order to sleep at night, I have to remove myself from the equation, pretending that the people I love voluntarily chose to expose themselves. Amy breaks up with a boyfriend and sends out a press release. Hall regularly discusses his bowel movements on daytime talk shows. I'm not the conduit, but just a poor typist stuck in the middle. It's an illusion much harder to maintain when a family member is actually in the audience.

The day after the reading Lisa called in sick and we spent the afternoon running errands. Winston-Salem is a city of plazas, mid-sized shopping centers each built around an enormous grocery store. I was looking for cheap cartons of cigarettes and so we drove from plaza to plaza. Lisa had officially quit smoking 10 years earlier and might have taken it up again were it not for Jessie, who according to the vet, was predisposed towards lung ailments.

"I don't want to give her secondhand emphysema, but I sure wouldn't mind taking some of this weight off. Tell me the truth, do I look fat to you?"

Not at all.

She turned sideways and examined herself in the front window of Tobacco USA. "You're lying."

"Well, isn't that what you want me to say?"

"Yeah," she said. "But I want you to really mean it."

But I had meant it. It wasn't the weight I noticed so much as the clothing she wore to cover it up. The loose, baggy pants and oversized shirts falling halfway to her knees. This was a look she'd adopted a few months earlier, after she and her husband had gone to the mountains to visit Bob's parents. Lisa had been sitting beside the fire and when she scooted her chair towards the center of the room, her father-in-law said, "what's the matter, Lisa, getting too fat? I mean, hot." "Getting too hot?" He tried to cover his mistake, but it was too late. The word had already been seared into my sister's brain.

"Will I have to be fat in the movie?" she asked.

"Of course not," I said. "You'll be just like you are."

"Like I am according to who," she asked, "the Chinese?"

"Well, not all of them," I said. "Just one."

She tugged at the hem of her shirt and asked how much I thought he weighed. In truth, he was half her size, but I lied, giving him an extra hundred pounds.

Normally if at home during a weekday, Lisa likes to read 18th century novels, breaking at 1:00 to eat lunch and watch a television program called Matlock. By the time we finished with my errands, the day's broadcast had already ended and so we decided to go to the movies, whatever she wanted.

She chose the story of a young English woman struggling to remain happy while trying to lose a few extra pounds. But in the end, she got her plazas confused and we arrived at the wrong theater just in time to watch, You Can Count on Me, the Kenny Lonergan movie in which an errant brother visits his older sister.

Normally Lisa's the type who talks from one end of the picture to the other. A character will spread mayonnaise onto a chicken sandwich and she'll lean over whispering, "one time. One time I was doing that and the knife fell into the toilet."

Then she'll settle back in her seat and I'll spend the next 10 minutes wondering why on earth someone would make a chicken sandwich in the bathroom.

This movie reflected our lives so eerily that for the first time in recent memory she was stunned into silence. There was no physical resemblance between us and the main characters. The brother and sister were younger and orphaned. But like us, they'd stumbled to adulthood playing the worn, confining roles assigned to them as children.

Every now and then one of them would break free, but for the most part they behaved not like they wanted to, but as they were expected to. In brief, a guy shows up at his sister's house and stays for a few weeks until she kicks him out. She's not evil about it, but having him around forces her to think about things she'd rather not. Which is essentially, what family members do. At least, the family members my sister and I know.

On leaving the theater we shared a long, uncomfortable silence. Between the movie we'd just seen and the movie about to be made, we both felt awkward and self-conscious, as if we were auditioning for the roles of ourselves. I started in with some benign bit of gossip I'd heard concerning the man who'd played the part of the brother, but stopped after the first few minutes saying that, on second thought, it really wasn't very interesting. She couldn't think of anything either and so we said nothing. Each of us imagining a bored audience shifting in their seats.

We stopped for gas on the way home and we're parking in front of her house when she turned to relate what I've come to think of as the quintessential Lisa story. "One time," she said. "One time I was out driving." The incident began with a quick trip to the grocery store and ended unexpectedly, with a wounded animal stuffed into a pillowcase and held to the tailpipe of her car.

Like most of my sister's stories, it provoked a startling mental picture. Capturing a moment in time when one's actions seemed both unimaginably cruel and completely natural. Details were carefully chosen and the pace built gradually. Punctuated by a series of well timed pauses. And then. And then. She reached the inevitable conclusion and just as I started to laugh, she put her head against the steering wheel and fell apart.

It wasn't the gentle flow of tears you might release when recalling an isolated action or event, but the violent explosion that comes when you realize that all such events are connected, forming an endless chain of guilt and suffering. I instinctively reach for the notebook I keep in my pocket.

And she grabbed my hand to stop me. If you ever, she said, ever, repeat that story, I will never talk to you again. In the movie version of our lives I would have turned to offer her comfort, reminding her, convincing her, that the actions she described had been kind and just. Because it was. She's incapable of acting otherwise.

In the real version of our lives, my immediate goal was simply to change her mind. "Oh, come on," I said. "That story's really funny and I mean, it's not like you're going to do anything with it." Your life, your privacy, your bottomless sorrow, it's not like you're going to do anything with it. Is this the brother I always was or the brother I have become?

I'd worried that in making the movie the director might get me and my family wrong. But now a worse thought occurred to me, what if he got us right?

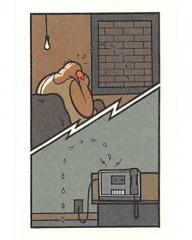

Dusk. The camera pans an unremarkable suburban street, moving in on a parked four-door automobile where a small, evil man turns to his sobbing sister saying, "what if I use this story but say that it happened to a friend?"

But maybe that's not the end. Maybe before the credits roll we see this same man getting out of bed in the middle of the night, walking past his sister's bedroom, and downstairs into the kitchen. A switch is thrown and we notice in the far corner of the room, a large, standing bird cage covered with a tablecloth. He approaches it carefully and removes the cover, waking a Blue-fronted Amazon parrot. Its eyes glowing red in the sudden light.

Through everything that's come before this moment, we understand that the man has something important to say. From his own mouth the words are meaningless and so he pulls up a chair. The clock reads 3:00 AM, then 4:00, then 5:00 as he sits before the brilliant bird, repeating slowly and clearly the words forgive me. Forgive me. Forgive me.

Ira Glass

David Sedaris. That story appears on his Live at Carnegie Hall CD and also in his new book, Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim. Coming up, what your six year old could probably teacher your doctor. No kidding. That's in a minute from Chicago Public Radio and Public Radio International when our program continues.

Act Two: Dial "S" For Sorry

Ira Glass

It's This American Life, I'm Ira Glass. Each week on our program, of course, we choose some theme, bring you a variety of different kinds of stories on that theme. Today's program, apologies. Stories of people struggling to apologize against some difficult odds. We've arrived act two of our show. Act two, "Dial S for Sorry."

In 1980, a New Yorker named Allan Bridge set up a telephone line that he called The Apology Line. And the way it worked was that you could call and confess to anything you wanted and you'd be recorded. Or you could call and you could listen to other people's confessions. And over time-- this is all pre-internet days. Over time, the whole thing turned into this little community of confession. People recorded messages responding to each other's apologies. Mr. Apology, Allan Bridge, would leave messages responding to messages himself. Or sometimes he would call callers off the line and talk to them.

Back in 1997 we played some recordings from the line on our program. We've never rerun it and we thought it might be appropriate to hear some of them today.

Man 1

Yes, I'd like to apologize because I have broke the town hall windows, I flooded the basement, I broke windows on the back of a store uptown. I feel pretty bad about it because I did so much violence. I'm only 16 years old. I did so much violence and if I was caught, I'd be in juvie hall for a pretty long time I'd say. I'm sorry for harassing the Republican officials, making the bomb threats and the death notices. I'm sorry for the terrorism, the fire bombing that the guy paid me to do to some guy's house. I'm sorry for the burnings in the streets of Smithtown, Long Island.

I'm sorry for the way I'm calling right now. I'm calling by way of a phony credit card. I'm sorry for harassing the teacher in school. I feel bad about it. I'd like to have a new lease on life.

What else? I'm sorry for just harassing a lot of people. For causing pain to my family. I felt so sad I was sick. I was sick by it. That's all I have to say. So long.

Man 2

Yeah, I want to apologize for something and maybe-- well, I guess it's too late to apologize for it, but I want to apologize for it now.

My mother was bedridden for a while and she had to get social security and welfare. And I had no job and I had no way of making money. And when she was hungry or thirsty I used to make her give me money to give her a drink. Like she'd have to give me $5 for a glass of water, $10 for a sandwich. Now she's passed away and I can't say I'm sorry to her. Because I know what I did was probably the most horrible thing in the world and I'll never be able to say I'm sorry to her. I hope I go to hell and burn there for this because it wasn't right. And if there's some way that she can hear me I just want to tell her I'm sorry. Thank you.

Man 3

I've never told anyone this except my shrink. I accidentally killed my younger sister when I was a very small child and it's haunted me all my life because I didn't really mean it. It was just a game to me and I was really too young to realize what I was doing. And I was putting her head inside a plastic garbage bag and putting a rubber band around her neck just to see her face turn blue. I guess it was a lot of fun and I didn't mean anything bad to happen. But I guess I didn't realize what would happen if I did this too long and she suffocated. I hid the plastic bag and I went out of the house. My parents weren't home. And they never found out. They thought it was crib death. They never found out I did it.

I've never been able to tell them. I think it would hurt them worse than losing her to find out that I did it. I kind of wish my parents could hear this tape, but I guess they never will.

Child

Hi, I'm a runaway and all I want to say is that I'm kind of sorry that I left. See, I'm 15 and I saw your number in the newspaper. When I saw it, I had to call because I mean, you walk around on the streets all day long just looking for someone that just might say, hey, want a place to go? Come with me. They'll give you food and everything. And they won't ask or anything back. That's all I want. I guess I take up too much time on the tape. But I just got to talk.

Ira Glass

The Apology Line doesn't exist anymore. Mr. Apology, Allan Bridge, died in August of 1995. When he did, the line was deluged with hundreds of messages from its regular callers, grieving. His wife, Marissa, says it was never clearer what The Apology Line had meant to people.

For years, people had used it to talk about all sorts of experiences.

Marissa Bridge

I think that maybe the word "apology" means something bigger than just saying you're sorry. Or at least maybe not the word, but the line came to mean to people a place where one could go and bring their feelings. To confess not necessarily about doing something wrong, but to confess about having a feeling.

Ira Glass

When he was alive, would you ever call the line or be tempted to call the line?

Marissa Bridge

I called the line in the beginning when I first knew him, before I moved in with him. I called the line from time to time.

Ira Glass

And you'd apologize for stuff?

Marissa Bridge

Well, yeah, sometimes. But more to get his attention than anything else I think. So he wouldn't forget about me up in Washington Heights where I was living.

Ira Glass

What would you apologize for back then? Do you remember what you would say?

Marissa Bridge

Oh, they were all like, you know, just to get his attention. Things like, I'm really sorry I was flirting with another guy or something like that. Much part of the mating game.

Ira Glass

But once you actually had a real relationship with him, you wouldn't call the line and you didn't feel a need to ever?

Marissa Bridge

No, but one thing that really struck me was after he died, I really turned into an Apology Line caller. Someone I would define as Apology Line caller. And the line was over, so when I really needed the line it wasn't there. I was just completely lost and I would have loved to have been able to call The Apology Line and have someone like Allan on the other side, very sympathetic and understanding, to help me get through it. But unfortunately, that didn't happen. I'm a much darker person than I was before he died and I think that I understand the caller's and the line much better than I even did before.

Ira Glass

He died in this scuba accident where he was hit by a jet skier who then fled the scene and wasn't caught. Have you thought about the kinds of people who would call the line, who used to call the line all the time, who had done bad things to other people and hurt other people, and then would flee the scene and nobody would ever know. Have you thought about those jet skiers in terms of that, in terms of the people who used to call the line?

Marissa Bridge

Yes, in fact, the person that hit him would also be a prime candidate for The Apology Line. Because we think that he knew that he did something because there were witnesses that saw the accident and they saw someone on a jet ski hit him. They circled around once and then took off. Yeah.

Ira Glass

But you can imagine those people actually calling the line? If they would have called the line, if the line had existed for them, what would have happen? What would Mr. Apology have said if he were around to say it?

Marissa Bridge

I think he would be pretty pissed off, but he would forgive them. I think that's how he would have gone for it. I think he would have been angry that he was hit. That was a total accident. But I think that if they would have apologized for hitting him he would have forgiven them. Because I think that forgiveness was a big part of his personality. I think he really believed in the power of forgiveness. And everyone can be forgiven if they're sorry. I think that's something that he really believed in.

Ira Glass

Marissa Bridge. The Apology Line is still down, but there's a website with clips and transcripts and a CD for sale, www.apologyproject.com.

[MUSIC- "I'M CONFESSIN' (THAT I LOVE YOU)" BY BRENDA LEE]

Act Three: Two Words You Never Want To Hear From Your Doctor

Ira Glass

Act three, "Two Words You Never Want to Hear from Your Doctor."

There are somewhere between 44,000 and 195,000 fatal medical errors in hospitals every year, depending on what study you look at. But those errors don't translate into 44,000 to 195,000 apologies from doctors. Starlee Kine says this may be changing, but very, very slowly.

Starlee Kine

Five years ago, 39 year old Michael Lang had a stomach ache that was causing him a lot of pain. That night he checked into the local emergency room. The staff looked at him briefly and decided his condition wasn't too serious. The family says his mother talked to a nurse and requested an ultrasound, but that was rebuffed. Michael was given morphine for the pain and told he'd be able to go home the next morning.

Overnight, he died of an internal hemorrhage and blood around his heart. The hospital called Mike's parents and told them that his condition had worsened, but not that he had died. They got in their car and rushed over. This is Mike's sister, Roxanne.

Roxanne

On the way there my parents start talking about taking him somewhere else, not realizing that he was already dead. And when they arrived at the hospital, no one was there to meet them and they took the elevator up to the second floor. And when the door opened, a lot of the nurses were standing there whispering. And when my mom looked at one of the nurses, she knew and she turned to my dad and said, he's dead, Ray.

And they ran down the hall to his room where Mike was lying in the bed with the IV still in his arm. It was hanging over the side and my dad tried to put it under the sheet, but was unable to bend it. The thing that they remember the most is going over to him and trying to hug him. And he was, you know, stiff and cold. That's their memory of their son.

Starlee Kine

It's not just the fact that the doctors didn't catch what was wrong with their son, but the way they were treated by the hospital that haunts Roxanne's family. How they were disregard when they asked for an ultrasound. How they were allowed to drive over thinking Mike was still live. And then how no one was waiting for them with the tragic news once they got there.

In the weeks that followed, the things the hospital did just made it worse, as far as the family was concerned. When asked why they hadn't been more attentive to Mike, the hospital said they'd been busy that night with an emergency accident. They denied all responsibility for Mike's death.

The town in Wisconsin where this happened is small. Roxanne's parents go to the same church as the hospital's CEO. Roxanne says they never talk. It's awkward. Almost the only communication they've had from him was in a letter he sent after Mike's death.

Roxanne

He basically said Mike didn't die of a medical error and we have no responsibility for his death at this hospital. We had several committees that investigated it and reviewed everything and we made no mistakes here. Basically, he said we didn't have any part in it. But still, no answers. Still no apologies.

Starlee Kine

No?

Roxanne

No. And the thing about the letter was is he addressed them by their first names, Ray and Betty. Dear Ray and Betty. To me, that was an insult when I read that. I was just like, how can you be so familiar with my parents when you can't even apologize for their son dying in your facility?

John Landdeck

Well, see, an apology, why do you apologize to somebody-- because you did something wrong?

Starlee Kine

This is the CEO of the hospital, John Landdeck. He and Roxanne don't see the situation the same at all. For him it's like this-- the hospital wasn't at fault from Mike's death. An independent medical commission that looked into the case cleared them of wrongdoing. And besides, he's not even sure the hospital didn't apologize.

John Landdeck

To the extent that we failed to communicate our sympathy with them, that's bad. But you know, a family facing the sudden loss of an otherwise normal, healthy, young man doesn't always hear and see everything that's going on either. And those nurses might have said things and we might have and the doctor might have that they completely missed in their grief.

Starlee Kine

Do you think when the family started saying stuff like, you know, there was a medical error, he died of a medical error. It was the hospital's fault, stuff like that that the hospital went on the defensive though?

John Landdeck

Well, we tried not to. I'm sure that everybody felt that way. If somebody says you're bad and you know you're not and the first thing is to set out to prove that you're right.

Starlee Kine

This is really like any fight when someone asks for an apology. One side wants to prove it's not their fault, the other wants acknowledgment that their feelings are valid. There's a lot of talking past one another.

Starlee Kine

Is part of the reason that you think you and your family and other families need to hear an apology so badly is because you're afraid that maybe when they don't say they're sorry that they don't actually feel sorry?

Roxanne

Most definitely. I remember from Mike-- in Mike's situation-- is we just wanted somebody to publicly acknowledge the fact that he died and that that was an awful thing. You know, whether he died of an error or not, it was an awful thing that he died. And nobody was saying that.

Starlee Kine

The reason doctors and hospitals don't apologize is actually pretty simple. It all comes down to malpractice insurance.

David Sousa

I think historically the party line has been gag orders.

Starlee Kine

This is David Sousa, president of Medical Mutual Insurance Company.

David Sousa

As people like us, as an insurance carrier, have seen our society become more and more litigious, it has caused us to go to our physician insureds and to caution them, unfortunately, that anything and everything that they may say in the context of a medical error, can be used against them to prove their negligence if they are sued by that patient.

When those kinds of things started happening, we started counseling doctors, much to our chagrin, you need to not have these conversations with your patients. Or if you do have to have them, they've got to be almost sterile in nature so that the patient can't come back and use that against you if they try to sue.

Over time, that has had an incredible chilling effect on the ability of doctors to just openly communicate with their patients when something goes wrong.

Starlee Kine

And you actually had these conversations with doctors where you would advise them to not say anything?

David Sousa

Repeatedly. Repeatedly. Absolutely.

Starlee Kine

This is all changing though. The shift began back in the '80s when Lexington, Kentucky Veteran's Hospital lost a series of malpractice suits and decided to try an experiment.

The doctors were told that they had to disclose fully and immediately any medical error to patients. And also, apologize if it was appropriate.

In 10 years, the hospital went from having some of the highest legal costs in the state to some of the lowest. Meanwhile, the laws in certain states started changing so that when a doctor apologizes it can't be used against them in a lawsuit. There are now laws like that in nine states. Some apply to any kind of apology made in any civil suit. The new ones specifically apply to medical errors. Again, David Sousa from the insurance industry.

David Sousa

Now in our state here North Carolina, a statement made that is tantamount to an apology can not be used against that health care provider to prove negligence in a court room. That's huge. It really opens the door now for us to say, now not only do we believe it's the right thing to do, but now you're protected when you do it. And that's huge. That's just giant.

Dr. Albert Wu

The apology. The apology. [LAUGHTER]

Starlee Kine

Tucked away in the basement of Johns Hopkins Medical School through a door that I thought was a fire exit, in a little room that reminded me of the smoking stairwell from college is a movie studio, an instructional movie studio. Dr. Albert Wu, an associate professor at John Hopkins, is shooting a training video here. It's called, "Disclosing Errors and Adverse Outcomes. The Who, What, Where, When, How, and Why of Disclosure." Or as I like to call it, being a doctor means never having to say you're sorry. Unless something goes wrong, then you really should.

For the past 15 years, Dr. Wu has been researching how doctors handle medical mistakes. He's talked to patient about what they actually want to hear and then traveled around presenting his findings to doctors via the magic of PowerPoint presentation.

His video walks doctors through the process of telling their patient something went wrong, baby step by baby step.

Dr. Albert Wu

Tips for disclosing. Before beginning, make sure the patient or family member is comfortable. Try not to put a desk or other barrier between you and the patient. Give the patient the opportunity to talk and ask questions about the situation. Do not ignore or dismiss strong emotions, even if you would prefer to do so.

If the patient is enraged acknowledge this by saying, I can understand why you are angry with me.

In the case of personal responsibility, express personal regret and make a sincere apology. You should say, I am sorry that I did this.

Starlee Kine

And that's that. There's no complicated formula or magic combination of phrases. It literally comes down to teaching doctors how to say the actual words, "I'm sorry."

Dr. Wu tells me that when he first started out, doctors didn't even have to tell their patients when they did something wrong, let alone apologize for it. He remembers on his first day as an intern he went to a woman's hospital room to give her a routine checkup and she had a heart attack before he could even start. A nurse was there with him.

Dr. Albert Wu

And the person at the head of the bed said, give this. And so I took this syringe and squirted 10 milligrams of morphine into the patient's IV. And it turns out 10 milligrams of morphine is a lot morphine. What she intended me to do, I think, was for her to get maybe a milligram. Or maybe two. But not 10.

She had been breathing very rapidly [HEAVY BREATHING] and it was about as clean a cause and effect relationship as one could ever see. I gave her an overdose of morphine and she stopped breathing.

Starlee Kine

The woman was rushed off to an emergency room and was ultimately OK. Dr. Wu, on the other hand, wasn't doing so good.

Dr. Albert Wu

I was left there standing in the room. Hospital rooms look funny when there is no hospital bed in them. The bed had been wheeled right out of the room, syringes had been ripped out of packaging, and bottles had been hung, and there was all of this stuff all over the place. And I just sort of stood there with sort of that tingly feeling that starts in your spine and goes up to your neck. It really is a little bit like the walls are closing in on you. Unfortunately, this head nurse was standing in the corner with her arms folded and she looked at me and said, "that was a lot of morphine." And we talked a little bit about what seemed to have happened and what might have been done differently. And then, in the end, she said, well, "I don't think that anyone really needs to hear about this." And that was it.

So as far as I'm aware, the patient's attending physician never heard about what had happened, the patient certainly never heard what happened. And I was relieved that I'd been let off the hook, but still felt a little uncomfortable.

When you make an error that hurts someone, you feel like you're the only person who has ever done such a thing. You feel completely isolated. There's a funny dynamic that's in effect. Doctors would like to believe that they help people. Patients desperately would like to be helped. And through a process of mutual denial, it's easy for everyone to pretend that this sort of thing happens rarely in any event, or should not happen at all. When in fact, it's quite common.

In a funny way, I think it's a relief to know that there is a policy that one should disclose errors that harm the patient.

Starlee Kine

So doctors feel relieved when they apologize to their patients. And often, they want to apologize to their patients. But Dr. Wu says that doesn't mean they're any good at it.

Dr. Gerald Hickson

So often there's an apology followed immediately by an excuse.

Starlee Kine

A small medical apology industry has recently sprung up with books, videos, and seminars, like this one with 40 doctors in North Carolina, set up by a local insurance company, and taught by Dr. Gerald Hickson from Vanderbilt University.

He warmed up the crowd by telling the story of a pregnant woman who was treated so poorly by her doctor that she vowed never to get pregnant again, just so she wouldn't have to see him anymore. At this seminar, it becomes pretty clear that most medical errors aren't dramatic. They're not matters of life and death. Most of them are things like forgetting to follow-up and giving your patient a referral, or being half an hour late while your patient sits in the waiting room.

Also, it's not always exactly clear if the doctors are to blame or not, even in the most seemingly cut and dry cases.

Dr. Gerald Hickson

Something else we often see that I worry about is an apology with what I call assignment of responsibility. A finger pointed in a direction to say, well, Ms. Jones, I'm just so terribly sorry that the nurses at this institution clearly can't count right. Right? You know exactly what I'm talking about.

Starlee Kine

In the years since Roxanne's brother died, she has sat on panels with doctors and policymakers talking about the need to be honest with patients and admit their errors. And she's met with doctors who have been trained in this whole new way of apologizing. And she's glad for the effort, but says that a real apology isn't only about the words.

Roxanne

The response that I get now when people find out, especially from health care that I lost a brother through medical error, they are in a hurry to say, I'm very sorry for your loss. Because that's what they're being taught. That they should say I'm very sorry for your loss. And for the most part, everybody's very sincere about it and I appreciate it. But you can see it's that they've been taught that phrase. That that's the phrase they should use.

Starlee Kine

How can you tell?

Roxanne

It's like the rush they need to get it out to me and this is the phrase that is used. You know, I'm sorry for your loss. So everybody in health care now learns how to apologize the right way according to all the training that's going on out there. So everybody that ends up having an error is going to hear the same thing. And they're going to hear it over and over again by people in health care the same way. And eventually, it's going to mean nothing to them because it won't be real anymore. It will be a programed response.

Starlee Kine

And then there are some doctors who are simply never going to change. At one of the apology seminars I went to I met this doctor who told me that he's so afraid of being sued that he tries to avoid talking to his patients all together. He actually said the words, "I live in fear." Not surprisingly, he was leery of letting me record him.

He told me that is was one thing to role play apologizing in a seminar of your peers. It was quite another thing to say it to an actual patient. He said every doctor he knows has been sued for malpractice. He just wants to reach retirement, which is eight years away. "I hope I make it," he said. He's terrified of saying something that will land him in court, no matter what his insurance company tells him, no matter what laws protect him. So he just tries to say nothing at all.

Ira Glass

Starlee Kine in New York.

Credits

Ira Glass

Well, our program was produced today by Diane Cook and myself, with Alex Blumberg, Wendy Dorr, Jane Feltes, Sarah Koenig and Lisa Pollak. Our senior producer is Julie Snyder. Elizabeth Meister runs our website. Production help from Todd Bachmann and Amy O'Leary.

[ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS]

The Apology Line story that was act two of our show today is on our first greatest hits CD from Rhino Records. Our website, www.thisamericanlife.org, where you can listen to our programs for absolutely free, or buy CDs of them.

Well, you know you can download audio of our program at audible.com/thisamericanlife. They have public radio programs, bestselling books, even the New York Times all at audible.com.

This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International.

[FUNDING CREDITS]

WBEZ management oversight for our program by Torey Malatia, who has something that he wants to share with everybody. Something he wants to say. Torey?

Man 1

I'm sorry for harassing the Republican officials.

Ira Glass

Good you got that off your chest. I'm Ira Glass, back next week with more stories of this American life.

Announcer

PRI, Public Radio International.