369: Poultry Slam 2008

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

From WBEZ in Chicago, it's This American Life distributed by Public Radio International.

[MUSIC - TURKEY BASEBALL SONG]

I suppose it's not enough this time of year that we eat millions of turkeys. Someone also went to the trouble to make up a song about turkeys getting the supernatural power to play baseball. We know they love Thanksgiving. Why wouldn't they enjoy our national pastime? Of course, there is no gobbling in baseball.

Well, during this time of year-- the beginning of the biggest poultry consumption months in these United States-- it is a tradition here on our radio show to bring you a program full of stories about turkeys, chickens, geese, ducks, fowl of all kinds. And for this year's program we have found stories about poultry and the supernatural, like turkeys playing baseball, except these stories will be true-- the ones you're about to hear.

We have people trying to invest chickens with magical powers. We have birds who may be emissaries from beyond the earth. We have priests using their priestly powers on the poultry industry. And we have chickens lifted heavenward and plucked of their feathers by mysterious forces no one can fathom. It is gods and chickens today on our show. Stay with us.

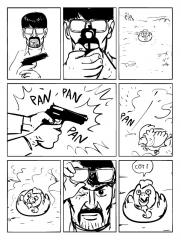

Act One: You Gotta Ask Yourself One Question: Do You Feel Clucky? Well...do Ya, Punk?

Ira Glass

And we begin in a faraway place, an ancient place, the mountains of Pakistan near the border of Afghanistan. Gregory Warner was living there.

Greg Warner

The story really begins with JD, an Afghan guy I met in Kabul. The first time I met him, he tried to pretend he was from the States. He sounds really American. Let me play you this voice mail message he left me.

Jd

Hey Greg. This is JD. I'm calling from Afghanistan, man. Where are you? I sent you an email. Hopefully you'll read it.

Greg Warner

Thing is, JD kind of learned his style from the US Marines. For five years, he was an interpreter for them. They also taught him how to shoot and how to dress. They even named him JD, short for Japanese Dude. Japanese, because they said he looked Asian, and dude because he's a dude.

Jd

Ciao, bitch.

Automated Voice

End of message.

Greg Warner

So when I was asked to go down to the Afghan border and do a story about smugglers, the first thing I did was call up JD and hire him as my translator. He'd stopped working for the Marines by then because he'd gotten married, and his wife said it was too dangerous. He was restless and up for an adventure. A week later we were in Pakistan, driving a Toyota through the streets of his old hometown, Quetta. It's a town popular with smugglers, because it's right on the border of Afghanistan and not too far from Iran. And it's in the middle of the mountains, almost impossible to control.

JD wanted me to meet his uncle, an ex-smuggler named Ali. Actually, Ali wasn't really JD's uncle, more like a distant cousin, 20 years older. Back when JD was a little kid, Ali would run operations to Turkey or Malaysia, smuggling heroin, or guns, or illegal aliens. And then a few years ago, Ali announced his retirement. The Americans are here now, he said. The game has changed.

When I meet Ali, he's grocery shopping in an outdoor market, but in this really commanding way. He stands some four or five feet from each stall, points a long arm at what he wants. He says, "Five kilo rice. Three Pepsi. Two kilo raisin. Send it home to my wife." And then he turns and strides to the next push cart, his loose clothes swishing around him like Laurence Fishburne in The Matrix.

Ali wears dark glasses. And he lost one eye in a gun battle, an injury that looks like it pretty much definitely should have been fatal. I'm thinking that Ali's going to introduce me to some smugglers for my story. But Ali isn't so interested in that. Instead he says he's going to go shoot guns in the mountains with some friends. And we're welcome to tag along.

Then Ali walks into a store. And he comes out with a cardboard box. On the outside of the box, it's stamped, Pampers. Inside the box is a live chicken. Then Ali closes the box, wraps it up in a scarf, and slings it over shoulder. We follow him and his three scruffy looking friends out of the market, past the last mud houses and into the mountains. That's how my day tracking human smugglers on the edge of a war-torn border turned into a day about a chicken.

"What's with the chicken," I ask JD. And the answer is not what I expect. He tells me that Ali's old friend has been arrested and is in prison. And Ali wants to spring him out. But just in case things go wrong with the jail break, Ali has bought his friend a magic amulet called a taweez. The taweez is supposed to protect whoever wears it from bullets. Before he gives it to his friend, he wants to test the taweez to see if it works, test it on the chicken.

"Wait," I say, "we're going to put the magic amulet on the chicken, and then shoot the chicken to see if it's invincible?" "Yeah," JD says, "these guys take religion really seriously."

We walk up into the mountains. And it's a beautiful morning, sun drenched rocks, dark caves, dry spindly plants over everything. The path is steep. And Ali tells me that back when he was a smuggler, before he'd agree to bring someone through mountains like this, he wouldn't take just anybody. Actually, he'd screen them first for health problems.

Ali

Heart problem.

Greg Warner

If they had a heart problem, say.

Ali

Stomach problem.

Greg Warner

Stomach problem.

Ali

We have blood problem.

Greg Warner

Blood problem.

Ali

We know about all the dark things. We check the person at first.

Greg Warner

So you give him a physical?

Ali

Yeah.

Greg Warner

It seems oddly responsible behavior for a smuggler, though of course he didn't want to get stuck on the side of the mountain with a half-dead guy. I ask Ali if he'd smuggle me. And he says, no. And then he starts to sing.

Ali

[ALI SINGING].

Greg Warner

And then he leaps on ahead over the rocks with his sack slung on his back like a one-eyed mountains sprite.

Ali

[ALI SINGING]

Greg Warner

After an hour or two, we stop in a little valley with a clump of bushes nearby. Ali puts down the sack. And from his shirt pocket he pulls out the amulet, the taweez. The belief in a taweez is older than Islam. Only in remote, superstitious corners of the world like this do the mullahs deal in this kind of magic. Ali got this one from a mullah. It's nothing fancy, a white scroll the size of a piece of chalk. Ali wraps it in blue plastic and ties it to the chicken's neck.

The effect does not seem particularly magical. Basically, it looks like a chicken with some garbage tied to its head. But for the experiment it'll do. Ali picks up the bird with both hands, sets it down in some dirt in front of a bush, not too far away either. Imagine a tennis court. If you're standing at the baseline, the chicken is about where the net would be. And then Ali pulls out a handgun from the waistband of his pants. The gun is old looking and blackened with use. And then his three friends pull out their guns. And there is a lot of loading, and cocking, and gun prep.

Ali stands up tall. And Ali is tall for an Afghan, about six feet. He holds the gun out with both hands, aims with his one eye, [GUNSHOT] and nothing happens. The next shot [GUNSHOT] hits the dirt right by the chicken's foot, pings up like in the movies. It's really close. And then Ali lifts his gun a third time. And there's just a click. And another click, click. "It's jammed," Ali says. "This never happened before." For a moment, we all take this in.

Then JD says, "Are you sure?" And he says, "Yeah, I use this gun to kill rabbits." And JD says, "Rabbits?" And Ali says, "Yeah, rabbits." And JD says, "You know the Marines shoot that gun with one hand." And Ali says, "Yeah no, this gun, you have to shoot with two hands." And JD says again, "Well the Marines told me--" And Ali cuts him off saying, "Hey, how much are the Americans spending on the Marines?" And JD takes the hint, and he drops the subject.

And then Ali takes his whole gun apart, laying out the pieces on a flat rock. And all this takes a couple of minutes. Meanwhile, the chicken just sits and waits. And I'm going to go out on a limb here on the radio and say that most of sentient creatures caught in gunfire would run.

And I'm sending little thought waves to the chicken, like, run, run. And this chicken is so just completely overconfident in this taweez.

Greg Warner

I think that taweez is working.

I say, maybe it's magic. And Ali just shakes his head like I'm crazy, like I'm the gullible one to believe too quickly in this taweez. We haven't finished our test. Maybe it made the gun jam, but Ali's got to be sure. If he's going to give this to his best friend, he's got to know it works.

Ali

[INAUDIBLE]

Greg Warner

Finally, Ali fixes whatever was wrong with the gun. The spring got caught on something. He doesn't know why. He reassembles the gun, and then he fires again. [GUNSHOT] And then he fires a fourth time. [GUNSHOT]

Ali

[SPEAKING FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

Greg Warner

And the chicken is still not dead. And Ali looks surprised. "How is this possible," he says. "I still haven't hit it. Really, how is this possible?"

Ali

[SPEAKING FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

Greg Warner

Next, Ali's friends each take their turn. [GUNSHOTS] That's three more misses. Ali shoots one last time, [GUNSHOT] and again it pings in the dirt. Ali puts the gun down, and he asks how many bullets we've shot.

Ali

[SPEAKING FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

Greg Warner

"OK," he tells everybody, "the thing works." He doesn't say it in a praise God in his infinite wisdom kind of way. He says it like a mechanic closing the hood of a car. OK, it works. And then JD says, "Can I shoot one?" And Ali shrugs, like, sure, let the kid have a go. And he hands him his gun. And JD lifts the gun with one hand like the Marines taught him, straight out in front. And he aims. And he squeezes off a shot. [GUNSHOT]

And all of a sudden, it looks like some invisible hand came and painted one of the chicken's feathers bright red. And then that red spot gets bigger. We all look at Ali. No one moves, not even the chicken, and it's bleeding. We watch Ali pull out his pocket knife. He strides with long steps over to the chicken, not happy at all. He grabs the chicken by the head and cuts through the blue plastic around its neck with one slice. Then he fishes out the taweez , and he chucks it into a bush. With the next stroke, he slices off the chicken's head.

Later, JD tells me that Ali spent $1,700 on that little scroll. But right now, JD is excited. He's saying, "Where did it hit? Where did I hit him?" And Ali says, "The chest. You hit it in the chest." He digs out the bullet with his knife. And he says, "This bullet is come from the US government." And I'm not sure exactly what he meant by that. But it didn't sound good.

JD, on the other hand, is doing a happy dance, still holding the gun. And then JD starts laughing. Then he says, "Look, he has eaten the heart."

Greg Warner

He just ate the heart?

Jd

Yeah, ow.

Greg Warner

Anyway, after that, there isn't much to do but eat the chicken the regular way. We gather brush wood, make a fire in the mouth of the cave, stick the chicken on a stick, and roast it, extra crunchy.

Ali

[SPEAKING FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

Greg Warner

Then Ali chats with guys, like he's trying to forget the whole thing. They don't talk about amulets, or guns, or Marines. Most of the lunch he just makes fun of me. "Look, he's skinnier than I am," he says. "He's so skinny, he'll be dead in 15 days." "Look at him," he says. "He eats too fast."

Ali

[SPEAKING FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

Greg Warner

Sitting here in this cave, we can see out for miles. And all up and down the hills there are other clumps of men in robes like us, also sitting around fires cooking lunch, like it has probably been for centuries. It's hard to explain, but out here it's easy to feel like this is all there is and all there ever will be. And Ali's risen up about as high as you can in this world. He went from poor mountain boy, an orphan in a tiny village, to mafia don. And then, all of a sudden someone like JD shows up. And that world doesn't seem like all there is anymore.

It's like you start your morning on a mystical pilgrimage with a magic amulet to rescue your best friend. And then, by the end of the afternoon, you learn it wasn't about magic at all. It was just a game of shoot the chicken-- a really expensive game of shoot the chicken-- that you lost to a cocky 23 year old who works with the Americans.

Ali

[SPEAKING FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

Ira Glass

Gregory Warner is a reporter based in Philadelphia.

Act Two: Winged Migration

Ira Glass

Act Two, Winged Migration.

Kathie Russo

So it was Saturday, January 10, 2004. And Spalding was in our apartment in New York with our daughter, Marissa, who was 16 at the time, and Theo, who was six.

Ira Glass

This is Kathie Russo. Her husband was Spalding Gray, who is best known for delivering monologues on stage like "Monster in a Box" and "Swimming to Cambodia." Both those monologues were also filmed as movies. Spalding Gray went missing on January 10, 2004. Witnesses say they saw him on the Staten Island Ferry that night. His body was finally found, pulled out of the East River two months later. Our show today is about birds and the supernatural. And Kathie Russo tells this story about that last night and the days immediately after it. As she said, her husband was with two of their kids that night. She was out that night. They have a third child, Forrest, who was 11 at the time. He was in Sag Harbor, Long Island with friends and a babysitter. They had a house out there too.

Kathie Russo

Spalding had dinner with the kids. And then it got to be about 7:00 PM. He said he was going to meet an old friend. And Marissa goes, "Oh that's fine. You know I'm here. I can watch Theo." And he went out. And about an hour and a half after that, he called to check in on the kids. Theo answered. And he said, how's everything going? He goes, good. He goes, well, I love you very much. And I'll be home soon. And we never saw Spalding again.

The next series of events still seem like a blur to me, even five years later. But the first thing I had to do was go report Spalding missing. I did that. And then I decided to send the kids home, back to Sag Harbor to join their brother. So I stayed for two days, did whatever I could, which was pretty much nothing. And after two days, I just decided I'm going back to Sag harbor to join all the kids.

So I'm driving on the Long Island Expressway back to Sag Harbor, and I get a phone call on my cell phone. And it was Theo. And he was all excited. And he said, "Mom, Mom, we came home today from school. And there was a bird, a little bird flying around the island in the kitchen." I said, "And then what did you do next?" He said, "Well we followed the bird. And Marissa followed him into the bathroom. And she tried to calm the bird. And she took a hat, and cupped it over the bird, and captured the bird, and went outside and let him out free."

And I was just so dumbfounded and awestruck. The first image that came to my head when he said that there was something-- a bird in particular-- circling over this island, was I thought of Spalding, and how for the last two years he had obsessively circled around that island talking to himself, just circling in total anguish.

You see, two years before that, we had been in Ireland celebrating his 60th birthday. And the second day there, Spalding and I were in a horrible car accident. Spalding suffered enormous head trauma. He was never the same. They actually had to put a titanium plate in his head. He was in and out of hospitals for two years after the accident. Doctors prescribed various cocktails of pills for him. Nothing worked, not even the 20 electric shock treatments that he had.

And the second thought I had when I heard about the bird was, was this a message from Spalding? Was he trying to tell us something? We've never had a bird in our house before. And I remember the Irish have this saying that if you find a bird in your house after someone dies, and it's alive, the person's soul is free. And if you find a dead bird, the person's soul is restless.

And I remember Spalding-- I'll never forget this story after his mother killed herself 35 years before. His father woke up the very next day. And next to his bed, where his slippers were on the floor, was a dead bird. And that story just stayed with me.

So that night after the kids went to bed, I went around the house. And I was making sure that another bird could not get into this house, because I wasn't going to take the chance of another bird coming into the house and dying. So I checked all the windows, and I closed all the fireplaces to make sure, to guarantee that there was no way a bird could come into our house.

And the next day I was at the dining room table reading the paper. And I looked up, and there was a bird across the table peering at me. And I just couldn't believe what I was seeing. So I yell out to the kids, who are in the other room. And they run in. And the bird takes off, and flies up the stairs. And we all follow it. And it goes into what's our office. And it's perched on top of this window. And I shut the door behind me. And for some reason, I held out my hands, thinking the bird might magically come to my hands. And I go, "Spalding, it's OK. You're safe now. It's OK. Come to me."

And Forrest and Theo are on the other side of the door going, Mom, why are you calling the bird after dad? And the bird just sat there staring at me. And then it took off. And it flew over my hands. And in between the space in between the door and the floor, it scooted out, went past the boys, flew down the stairs-- and we had already opened up the kitchen doors-- and it flew out the kitchen doors. And it was safe. And it was gone.

The next day, I'm in the kitchen. And Forrest calls out from the TV room. He was watching cartoons. He goes, "Mom, the bird's back. It's at the end of the couch." So before I even go into the room, I open up the kitchen doors, just to make sure we have an exit for the bird. And I run into the family room. And sure enough, there is the bird.

And it has become a drill now. This is the third consecutive day with the bird in our house. And we follow the bird around. And this time it goes through the living room, then it comes back into the kitchen. And I actually got the camera out. And I took a picture of it. And the bird flew out, just like that. It was gone. And two months later, they found Spalding's body in the East River.

I think with suicide, in particular, it's a really hard death to digest. There's a lot of guilt. You go back and back. And you get into that mode of, I should have done this. I could have done that. It's a seesaw of guilt and forgiveness.

So last year was my 47th birthday. And I was feeling kind of blue. And I was really missing Spalding. And I went on this bike route that the two of us used to take together. And it ends up by the water. And just before I got to the water, I saw this little, brownish gray bird sitting on the side of the road, just like the one that we had in our house.

And I passed by it on my bike. I ride pretty fast. But something told me, go back. And I did. And the bird was just sitting there. And I'd get up close to it, and it didn't fly away. So I figured the bird was hurt. And I'm looking at the bird, crouching over it, and this jogger goes by me. And he said, "Oh, that bird was there two hours ago when I started my run."

So I raced back home on my bike. And I went into the house. And I collected a shoe box. And I filled it with grass and bird seed. I got some rubber gloves, and I drove back to where the bird was. And the bird was still there. It was about a mile from my house. And it's just looking up at me. So I thought it was really hurt. And I tried to scoop it into the shoe box. And it just gets up, looks at me, and flies away. There's nothing wrong with it. Wings were fine. I saw it flying off into the distance.

And I thought-- it just hit me like a ton of bricks right at that moment-- there was nothing I could do to save this innocent little bird, which, in the end, he was fine. He flew away. And there was nothing I could do to save Spalding.

Ira Glass

Kathie Russo. Coming up, when men of God meet men of chickens. That's in a minute, from Chicago Public Radio and Public Radio International, when our program continues.

Act Three: A Pastor And His Flock

Ira Glass

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Each week in our program, of course, we choose a theme, and bring you a variety of different kinds of stories on that theme. Today, as we enter the period between Thanksgiving and Christmas, the greatest poultry consumption time of the year in our country, we bring you our annual Poultry Slam. Most years on our show that means stories about fowls of all kinds. This year, we're devoting the hour to stories about birds and the supernatural. And specifically, most of these stories seem to be about chickens and God. We have arrived at act three of our program. Act Three, A Pastor and his Flock.

Working in a poultry processing plant is probably one of the most unpleasant jobs you can have in this country. It's smelly, it's wet, it's dangerous. Workers get nicked and cut by small knives and scissors. They get carpal tunnel from making the same hand and arm motions over and over. A recent Wake Forest University School of Medicine study of poultry workers found an astonishing 70% of the workers at one North Carolina plant said that they had gotten sick or injured in the previous year at their jobs.

The job pays badly too. And as a result, many of the people who do it are immigrants, Latinos mostly. It's also the biggest and fastest growing sector of the meat industry. Nearly a quarter million people work in poultry plants. So you would think this would be a perfect industry for unionization. But barely any poultry plants are represented by a union, especially in the South.

And that's where the church comes in. The church, especially the Catholic Church, is one of the few institutions doing outreach to poultry workers, giving them space to meet, distributing information about workers' rights, speaking out about bad conditions. And sometimes organizers use the church to intervene with company management in a very, very personal way. Sarah Koenig tells the story of one company called Case Farms and a plant they have in Morganton, North Carolina, in one of the least unionized states in the country.

Sarah Koenig

Case Farms in Morganton has been something of a poster plant for labor problems. Worker complaints there were so notorious, so widely publicized, they're partly what prompted the secretary of labor to announce in 1996 that he would investigate the poultry industry. "Sweatshop conditions," he said, "will not be tolerated."

In 1995, three young workers got mad about conditions at Case Farms. They were being denied bathroom breaks, they said. And the speed of the production line was dangerously fast. They went to talk to a manager named Ken Wilson. He told them they either had to go back to work or leave the plant. When they didn't move, he had them arrested. "We had no choice but to do what we did," he told The Charlotte Observer.

The workers responded by doing what poultry workers never do, voting in a union. The company fought that union for five years-- never giving it a contract-- until finally, in 2001, the union just pulled out. Four years later in 2005, the workers tried again. And again, one of the central figures in the plant's anti-union campaign was Ken Wilson, the manager who called in the police in 1995. He was director of human resources, but even more than that, he was the public face of the plant.

Francisco Risso

I've had an opportunity to meet with him at the plant itself when we were negotiating about the conditions.

Sarah Koenig

Francisco Risso is director of the Western North Carolina Workers' Center, which advocates for poultry workers.

Francisco Risso

And I think the last meeting was talking about why they shouldn't wage this anti-union campaign if the workers wanted to have a union. But his position was very clear that the company would be willing to spend any amount of money to keep the union out.

Sarah Koenig

Was is it overt, like he literally would say, "We are willing to spend any amount of money to keep this union out?" Or was it more oblique than that?

Francisco Risso

It was pretty overt like that. I would characterize it like what you just said. Believe or it not.

Sarah Koenig

Wow, so there was no reading between the lines. It was just--

Francisco Risso

No, that's pretty much what he said. We're ready to fight this until the end.

Sarah Koenig

When I reach Ken Wilson on the phone, he's just as direct with me as he was with Francisco. Here's what he thinks of labor unions. "They're just a competing business. To make money, they need members. And the way they get members is by convincing workers that they're being mistreated."

Ken Wilson

So their job is to convince the employees that the company is doing something wrong. I personally feel that the company was looking out for the best interest of the employees. We run a safe plant. So we run a business. They run a business. And at the end of the day, we're going to do what's best for our business.

Sarah Koenig

Knowing Ken Wilson's attitude, Francisco turned to God. He pulled out a tactic that's being used with more and more frequency at workers' centers all over the country. Instead of just using the church to help organize the workers, he would use the church to try to get to management, to get to Ken Wilson.

A coalition of tomato pickers did it in south Florida in their fight against Taco Bell. They enlisted the United Methodist Church. The head of Taco Bell's parent company was a member. Cintas commercial laundry workers have done it. It was used at a candle making company in Arkansas. In Texas, the Workers Defense Project has held prayer vigils outside employers' houses in their suburban neighborhoods. They even distributed flyers at an employer's church, telling his fellow congregants he was withholding pay from construction day laborers. They got a restaurant owner's rabbi to intervene on behalf of workers who were being paid below minimum wage.

It might not sound like the toughest angle to take. But it's one of the last, best tools worker rights advocates have at this point, especially in states down south, where unions have so little influence. Instead of the usual demonstrations and legal challenges, they're playing the faith card, reminding bosses of their moral obligations to their employees. One organizer told me it's more effective than calling in the lawyers. But it doesn't always work, as Francisco discovered at Case Farms when he tried it himself just as the union vote was approaching.

Francisco Risso

Somewhere around that time, I guess, we found out that he was a member of the local Episcopal church. My wife attended church there. And so through her I knew the pastor there, the priest, Revered Walker. And so I found out if he knew Ken, what the relationship was like. And then I asked him if he would be willing to speak with Ken and talk about what the church says about workers and about how we're supposed to treat the poor.

Sarah Koenig

Why did you think an appeal to his faith, or his belief in the Bible, or something would be more effective than a pocketbook argument?

Francisco Risso

I think what I was hoping for was that he would be open to having a good discussion with the priest, and maybe to really faithfully reflect on what the situation was, and reflect on what the faith had to say about it. Not so much that he would be shamed into doing something, but that his heart would really be touched. And he would see how he's supposed to act.

Sarah Koenig

Was it also partly that just, frankly, the pocketbook argument wasn't working?

Francisco Risso

Yeah.

Sarah Koenig

So from your point of view, it's like, well what else can you appeal to, really?

Francisco Risso

Uh-huh. I think that that's the basic-- that's the kind of thing that if we had anything in common with our enemy, with our adversary in this, that it was that, that you have a shared, proclaimed faith.

Bruce Walker

My name is Bruce Walker, and I am rector of Grace Episcopal Church in Morganton, North Carolina.

Sarah Koenig

Bruce Walker had come to town three years earlier knowing nothing of Case Farms or the problems there. No more than one or two Case Farms workers attended his church, which was mostly white and middle class. But Father Walker did know Ken Wilson. And he thought he was a nice man. When one of Ken's co-workers was killed in a car accident, Ken had asked Father Walker to come to the plant and do some grief counseling. And it had gone well. Through Francisco though, Father Walker was learning about the safety complaints at Case Farms. And he was sympathetic. Then Francisco asked him to come to the plant on the day of the union vote to talk to Ken. Father Walker was a little hesitant at first.

Bruce Walker

I wasn't naive. I knew that doing that, the possibility of it not going well, turning out well, was there. And there would be the possibility of alienation down the road. And I didn't want that. And when I went that morning, it was pretty early. I saw Francisco. He introduced me to some of his co-workers and friends.

And I did see Ken there. And I went over and spoke to Ken, and told him I was there to be supportive of this process. And I did suggest to him that if I could be helpful in mediation, I would be glad to do that.

And he had told me before that he was interested too in the rights of the workers and their safety. And I told Ken, I said, I don't see there's any difference in that idea. I think everybody here wants the workers to have a safe place. I don't know that we have the same road or the same method of doing that. But he listened. And he was nice enough with me. But I could tell he was flush. All the signs were there that I 'd stepped into it big time. I got the distinct feeling that he wished I had not been there that day.

Ken Wilson

I was walking out the front door of our plant, going across the street. We have another small office across the street.

Sarah Koenig

Ken Wilson remembers the whole thing a little differently. It was a more casual meeting.

Ken Wilson

And he was walking down the street. And we just happened to run into one another.

Sarah Koenig

Were you surprised to see him there?

Ken Wilson

Oh yeah.

Sarah Koenig

Ken also remembers their conversation a little differently. He says Father Walker told him he had mixed feelings about being there that day, since he had parishioners on both sides of the union issue, Ken and another guy. And that he was there to support both of them.

Ken Wilson

He said that he would be willing to mediate or to do what he could to bring the groups together. And of course I explained to him that it was an election. And in an election, you would have a winner and a loser. And at the end of the day, it would be left up to our employees to make that decision.

Sarah Koenig

It's not so much what Father Walker said that day that bothered Ken. It's how the whole thing looked.

Ken Wilson

Under the circumstances, I would rather that he not had been there. But I guess the only word that would describe it would be disappointed.

Sarah Koenig

What was disappointing about it?

Ken Wilson

His presence.

Sarah Koenig

Did you read it as in support of the of the union?

Ken Wilson

I would think from anyone else's perspective, they probably would have felt so, yes.

Sarah Koenig

Oh, you're saying that the way it looked was as if your priest had come in favor of the union.

Ken Wilson

Exactly.

Sarah Koenig

I see. It doesn't look great for for a manager's priest to be showing up.

Ken Wilson

[LAUGHING] Kind of a poor reflection on the manager, isn't it? Maybe I should up my tithe, don't you think?

Sarah Koenig

Did you say up your tithe?

Ken Wilson

Yeah.

Sarah Koenig

Yeah, right. Well precisely, precisely. Do you think the church-- is there a Christian argument to be made that, look we need to fight for the poor and for human rights. And we need to be involved with this stuff. And it is our place to show up and do this work?

Ken Wilson

The church has a right to do as it sees fit. My only request from any church group is to make sure they get all their facts before they take a position.

Sarah Koenig

From Ken's perspective, the facts were these. The workers voted to keep the union out that day, 296 to 225. From the perspective of those who wanted the union though, the no vote was the result of a long and intimidating anti-union campaign.

Father Walker says his relationship with Ken Wilson pretty much ended that same day. He got the feeling that Ken just didn't think it was any of his business. Here's Father Walker.

Bruce Walker

Perhaps he felt that my role was about more traditional things, like conducting worship on Sunday morning and visiting the sick. And as far as engaging in anything that was involved in injustice, that I was out of my realm. That's the feeling I got. And that's more of a feeling. And I think he alluded to kind of, what are you doing here? This isn't where you should be.

But I see just the opposite. I think that's the way a lot of people feel these days about clergy. But at the same time, as a Christian I look at Jesus as an example of what we're to be about. If you note through scripture, most of the time, Jesus is out on the road, so to speak, preaching from a mountaintop or by the seashore, out in the community going from one place to the next. Rarely is he contained within a building. And maybe that's-- as people's guide, we need to be outside our confines, more out into the world.

Sarah Koenig

Ken Wilson says he doesn't remember quitting Grace Church exactly, at least not consciously. But that's how it seemed to Father Walker. He called Ken a couple of times after that, wrote him a reconciling note. But he says he never really saw him back in church. In any case, about a year after the union vote, the Wilsons moved to the other side of the state, near Raleigh.

Sarah Koenig

Did you-- afterwards, considering it didn't seem to actually go so well-- did you regret talking to him? Did you regret taking that step?

Bruce Walker

Maybe a little at first, but not now. And if I have a regret, probably it's that I didn't do more to be helpful in that situation. I didn't go back to him the next day or the following day, and say, we really need to talk. Or maybe get with Francisco again, and say, how are you feeling, and how can I help you more? If I have any regrets, it's probably that I didn't do enough.

Sarah Koenig

Francisco doesn't think Father Walker failed. Maybe he didn't change Ken's mind that day. But who knows? In a year or two it could sink in. The Case Farms fight is still going on. The workers haven't given up. They're still talking about unionizing. Right now they say the company is trying to fire about 100 employees unfairly, including many experienced workers, in order to deny them benefits, or just get rid of people who tend to complain and organize.

Francisco and a church deacon met with two newer managers at the plant recently to talk about the firings, but they didn't get anywhere. So now Francisco is trying to find out where these managers go to church to see if their priests will talk to them. Workers at Case Farms are pretty pessimistic at the moment, Francisco says. And it's easy to see why. But he himself isn't. He believes people are basically good, which means the union-busting manager is always just a conversation away from conversion.

Christianity is full of examples like that, he says. Think of Saul, who persecuted Christians until a vision of Jesus blinded him on the road to Damascus. After that, he was Paul the Apostle.

Ira Glass

Sarah Koenig. She's one of the producers of our program.

Act Four: Twistery Mystery

Ira Glass

Act Four, Twistery Mystery. We now turn to Wayne Curtis, who has been puzzling over an unexplained phenomenon involving chickens, a riddle that is nearly two centuries old.

Wayne Curtis

I was researching tornadoes, leafing through 19th century newspaper accounts of the havoc they caused. And I found it was hard not to notice the sheer amount of poultry involved. It's mostly chickens, sometimes turkeys, rarely geese. The birds typically show up about 2/3 of the way into an article, after the description of entire barns being hoovered up into the sky, or bits of straw piercing a fence post. Sometimes whole flocks are ingested by the twister, and scattered lifelessly across the landscape like large snowflakes. But more often it's just a few birds. And these often attract the attention of newspapers for one reason. They're alive and clucking, but plucked cleaned as Butterballs.

When I came upon the first reference to a tornado-plucked chicken, I jotted it down as a freak occurrence. But then I came across another, and another. It turns out newspapers are filled with dozens-- if not hundreds-- of similar reports of naked poultry. A few examples. Rhode Island 1838, chickens, quote, "were seen walking about in all their naked simplicity after the spout had passed on." Missouri 1877, quote, "feathers were blown from chickens." Iowa 1893, quote "chickens were found alive and completely stripped of their feathers." And the year 1878 was a notably harsh one for poultry. In North Carolina, nearly 1,200 chickens were sucked into the sky and quote, "left free of feathers and ready for the stew pot."

If you were living in the 19th century and you wondered what a vengeful God looked like, a tornado would have been a pretty good representation. It had that whole finger of death thing going on, descending from the sky and randomly smiting and destroying. But this was a God given to occasional whimsy. The tornado would take a house and reduce it to splinters, but deposit a woman, still in a bathtub, atop a tree. Or it would take a chicken, strip it of its feathers, and set it free.

In 1842, a pioneering meteorologist in Ohio named Elias Loomis decided that naked chickens were not just a curiosity but a key that would unlock the secrets of tornadoes. At the time, virtually nothing was known about tornadoes, what caused them, how fast their winds could go, what was going on inside of them. Loomis figured that if he could calculate the speed at which wind blew off a chicken's feathers, he would have the first scientific estimate of the wind speed inside a tornado.

So he loaded a freshly killed chicken into a six pound cannon, pointed the gun skyward, lit the fuse and stood back. The cannon roared. The feathers soared to a height of 20 or 30 feet at a velocity Loomis estimated to be 341 miles per hour. He carefully examined the evidence and found the feathers had indeed been plucked clean. The only problem was with the chicken. It had been blown into small fragments quote, "only a part of which could be found," Loomis wrote. And so, no scientific conclusions could be drawn.

Loomis didn't give up on chickens. He still believed they held some of the secrets to tornadoes. Another theory floating around was that the funnel of a tornado contained a pocket of astonishingly low barometric pressure. Maybe, Loomis thought, when a chicken was sucked into a tornado, the air in its hollow quills expanded so rapidly that the feathers basically exploded out of the chicken's skin. To test this, Loomis put dead chickens in vacuum jars, then sucked out the air. The experiment was no more conclusive than the cannon. The feathers remained unmoved, still attached to limp chickens.

What Loomis did next was excellent news for the chickens of Ohio. He abandoned the study of tornadoes, and went on to explore theories of the aurora borealis.

After that, weather researchers pretty much ignored poultry for more than a century. Then, in the 1970s, there was a minor eruption of renewed interest in tornado-plucked chickens. In part, we can thank the Atomic Energy Commission for this. They wanted to make sure that nuclear reactors were being designed to withstand the worst possible tornado. To do this, they assembled a team of civil engineers and meteorologists from Texas Tech to figure out what exactly that maximum possible tornado might be. The team decided that it would be prudent to chase down stray tornado myths-- no matter how bizarre-- to ensure that nothing inexplicable would slip by.

Where did the chickens fit in? One of the myths they set out to disprove was that tornadoes could produce bizarrely high wind speeds-- as much as 800 miles per hour-- and that it was these high wind speeds that removed feathers from chickens. But the team quickly discarded this idea when they learned that chickens could start to lose their feathers in winds as little as 30 miles per hour.

Then in 1975, an atmospheric scientist named Bernard Vonnegut-- the brother of writer Kurt Vonnegut-- introduced a new theory about why chickens lose their feathers during tornadoes, fear. In other words, when chickens got scared, their feathers loosened. In a paper he published entitled "Chicken Plucking as Measure of Tornado Wind Speed," he said quote, "possibly this may be a mechanism for survival, leaving a predator with only a mouthful of feathers and permitting the bird to escape."

It was an elegant theory. And it became a widely accepted answer to the historic question about de-feathered chickens.

As a theory, it has just one downside. There doesn't seem to be a single person in the business of studying poultry who finds it even vaguely plausible. Or I couldn't find them anyway. Wayne Kuenzel is with the Center of Excellence for Poultry Science at the University of Arkansas. And he told me that the chicken industry has spent huge sums trying to figure out how to pluck chickens quickly and efficiently. If all it took was a good fright, poultry processing plants would be filled with animatronic coyotes. Plus, he pointed out, from the perspective of evolution, it doesn't make much sense for a chicken to lose its flight feathers when trying to escape predators.

So basically, we're back to where we were about 1840. We still don't know why some chickens ended up running around without their feathers after tornadoes. The naked chickens have had their encounter with science. And the naked chickens have pretty much won.

Ira Glass

Wayne Curtis is a writer in New Orleans. He is the author most recently of And a Bottle of Rum: A History of the New World in Ten Cocktails."

Act Five: Chicken Coop For The Soul

Ira Glass

Act Five, Chicken Coop for the Soul. Shalom Auslander grew up as an Orthodox Jew, attending religious school in a community of Orthodox Jews. And he has this story to end this show about supernatural forces and chickens.

Shalom Auslander

When Yankel Morgenstern died and went to heaven, he was surprised to find that God was a large chicken. The chicken was about 30 feet tall and spoke perfect English. He stood before a glimmering, eternal coop made of chicken wire of shimmering gold. And behold, inside, a nest of diamonds. "No freaking way," said Morgenstern. "You know," said Chicken, "that's the first thing everyone says when they meet me. 'No freaking way.' How does that make me feel?"

Morgenstern threw himself at Chicken's feet, kissing his enormous, holy claws. "Hear O Israel, the Lord is your God, the Lord is one," Morgenstern cried out. Chicken stepped back and shrugged. "Eh," he said, bobbing his enormous head. "What?" Asked Morgenstern. "I don't know. What's that supposed to do for me? Hear O Israel?" he asked. "How's it go again?" "It's Shema," Morgenstern said with hesitation, "The prayer. We say it twice a day."

Chicken stomped around in a circle before settling down in his holy nest of nests. "Yeah," he said, "I know. I've been hearing it for years. Still not sure what it means though. Hero Israel. Hero, like the sandwich?" "Not hero like the sandwich," snapped Morgenstern. He stood up, clutching his black felt hat in his hand. "Hear O Israel. It means that you are one, that you are the only, you know, God."

That last word didn't come easily. "Of course I am," said Chicken. "Do you see any other chickens around here? Hey Gabe. Gabe," called Chicken. "Is it Hero Israel, like the sandwich, or Hear O Israel?"

A stocky old man appeared from the clouds. He wore a pair of dirty Carhartt overalls and smoked a cigarette. "It's hero like the sandwich sir. You are quite correct." He turned his head sharply to Morgenstern. "Morgenstern?" he asked. "Yes." "Follow me." "Gabe," he said extending his hand to Morgenstern as they walked through the nothingness to the nowhere.

"As in Gabriel, right?" asked Morgenstern. "Right," said Gabe. "I'm sort of the head ranch hand around here. I make sure Chicken has enough feed and water. I clean his coop. You know, general maintenance." "Couldn't the Chicken just create his own food?" asked Morgenstern. "Not the Chicken," said Gabe, "just Chicken. And no he can't create his own food. He's a chicken."

Morgenstern asked Gabe where he was taking him. "Nowhere," he said, "this is what we do here. Wherever you go, there you are." "Christ," cried Morgenstern, "you're Buddhist. Damn, I knew the Buddhists were right. Always so happy and peaceful." "He's not a Buddhist," interrupted Gabe. He paused to light a cigarette, Marlboro Reds. "He's a chicken."

"I need to go back to Earth," Morgenstern blurted out. "Earth, why?" Morgenstern turned to face Gabe. "Let me tell them, Gabe. Please, let me tell my family, just my family, Gabe. He's a chicken, not Hashem, the one true judge, not Adonai, the Lord Almighty. Oh, the years I wasted. Let me tell them so they don't have to jump through the hoops I did, trying to please some maniacal father who art in heaven. Nine children, Gabe. Nine full, happy, worry-free lives they should have. Let them drive on Saturday. Let them eat bacon. Let them get the lunch special at Red Lobster. McDonald's, Gabe. Do you have any of those fries up here? Do you? What does a hamburger with cheese taste like? Please, let me tell them Gabe."

Gabe took a long drag from his cigarette and shook his head. "They won't listen," he said. "I've tried telling a few myself. But you want to go back to Earth? Go. Go back to Earth." Morgenstern hugged Gabe tightly. "Don't you have to clear it with the Chicken?" "Not the Chicken," said Gabe. "Just Chicken. And no, I don't. Chicken doesn't care either way." He flicked his cigarette butt off to the side. He gets his feed in the morning, and his droppings cleaned in the afternoon, and that's all he really wants to know. I'll see you in a couple of years."

Morgenstern awoke. He rolled his head slowly to the side and saw his wife and daughter Hannah sitting at the table in the hospital room eating their dinner, chicken. "Don't eat," was all he could manage. His wife jumped, startled at his sudden awakening. "Bar Hashem," she clapped. "Blessed is the Lord who makes miracles happen every day. Don't shake your head, Yankel. You have tubes in your nose. Hannah come quick. Your father is alive."

His daughter approached cautiously, holding a barbecued chicken drumstick in her hand. "May Hashem grant you a full and speedy recovery," she mumbled in Yiddish while staring at her shoes. She spotted a piece of barbecued God on her blouse, picked it off with her fingers, and popped into her mouth. Morgenstern groaned and passed out.

Friday afternoon, he was back home in his very own bed. He had decided to put off telling his family about Chicken until he was out of the hospital. He would tell him tonight as they gathered around the Sabbath table. He would speak to them the word of Chicken, and they would be freed, maybe jump in the car afterwards, catch a movie.

When the sun had finally set, and the Sabbath had finally arrived, Morgenstern pulled himself into his wheelchair, took a deep breath, and rolled himself into the dining room. His wife had set the table with the good tablecloth, the good silverware, and the good glasses. He watched her light the good Sabbath candles, covering her face with her hands and silently praying to a god who wasn't there.

"Please hear my blessings," she prayed to nobody. She'd have had better luck with a handful of scratch, thought Morgenstern. Maybe some cut up apple. She turned to him with love in her eyes. "Got tsu danken," she said in Yiddish. "Thank God." She came to him, knelt beside his wheelchair, and hugged him. "I have to tell you something," he said. "I know," she sobbed into the good napkin. "I know." "I don't think you do."

He rolled away from her. "When I was dead," said Morgenstern, "I met God." "We all meet God every day," said his wife, "if only we know where to look." "No, exclaimed Morgenstern, "you're not listening. How do you think I got back here?" he asked her. "Who else but the All-Merciful would send you back to me?" She replied. He could take no more. "Who?" shouted Morgenstern as he wheeled himself around to the head of the table. "I'll tell you who."

The loud voices attracted the children. And they gathered slowly around the Sabbath table. "Let me tell you a little something about your All Knowing. Let me tell you a little something about your All Merciful." Morgenstern looked from Shmuel to Yonah to Meyer to Rivka to Dovid to Hannah to Deena to Leah to little Yichezkel. The children were all showered, their hair neatly combed, and dressed in their finest Sabbath clothes. She looked at his wife. She was wearing his favorite wig. "Children," he began. "God," he said, "is," he continued, "a," he added.

The light from the Sabbath candles flickered in the eyes of his children. Little Meyer was wearing a brand new yarmulke and couldn't stop fidgeting with it. Shmuel held a handful of Torah notes from his rabbi he would read after the meal. And the girls would be looking forward to singing their favorite Sabbath songs. "God is a what?" Asked little Hannah.

He couldn't do it. "God," Morgenstern said to his children, "is a merciful God." His wife came to his side. "He is the God of our forefathers," he continued. "Blessed is God, who in his mercy restores life to the dead." The children cheered. Morgenstern closed his eyes and hugged his children tightly. His wife bent over and kissed him gently on his forehead. "May his kindness shine down on us forever," she whispered. She smiled then, went into the kitchen, and brought out the soup. Chicken.

Ira Glass

Shalom Auslander. This story first appeared in his book, "Beware of God."

Credits

Ira Glass

Well our program was produced today by Sarah Koenig and myself with Alex Blumberg, Jane Feltes, Lisa Pollak, Robyn Semien, Alissa Shipp and Nancy Updike. Our senior producer is Julie Snyder. Production help from [? PJ Vote ?] and Aaron Scott. Seth Lind is our production manager. Music help from Jessica Hopper.

[ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS]

This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International. WBEZ management oversight for our program by our boss, Mr. Torey Malatia. And call him sentimental, call him crazy, every Thanksgiving he does the same thing.

Wayne Curtis

Take a chicken, strip it of its feathers, and set it free.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American life.

Announcer

PRI, Public Radio International.