370: Ruining It for the Rest of Us

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

There are people who drive us crazy at our jobs, but science hasn't given that particular problem a lot of thought. Recently, a guy named Will Felps may have made some small progress in this area. He wanted to figure out if one person in the workplace can ruin a workplace. Not just disrupt the way that people get along and fill coworkers with weird feelings and uncomfortable moments that they think about for hours afterwards, but could one person actually lower productivity? Does one bad apple spoil the whole bunch?

Will Felps

First off can I maybe just describe a little bit what kind of behaviors count as bad apple behaviors?

Ira Glass

This is Will Felps. I reached him on the phone in the Netherlands, where these days he is an assistant professor of management at the Rotterdam School of Management. But back when he was in grad school doing this research, he read all the relevant studies on teamwork and group dynamics looking for clues about bad apple behavior. And he didn't find much. But he did find-- buried in correlation tables and footnotes-- three personality types, three kinds of behavior that seem to hurt group dynamics and group performance in a bad apple sort of way.

Will Felps

And these three sets of behaviors are-- well in layman's terms, you say someone who is a real jerk, who attacks or insults others, someone who is a slacker, who does less than they can, and then finally someone who is a depressive pessimist. So if you have a team member or an office-mate who's a real jerk, slacker or depressive pessimist, there's a chance-- and actually maybe a fairly good chance-- that they might spoil the barrel. And so what we do in the laboratory is that we create bad apples in the laboratory and see what effects they have. We create these by hiring confederates.

Ira Glass

Now you're saying confederate. You mean you hire an actor?

Will Felps

Exactly. Yeah, so we hire an actor. And in particular, what I did is I just advertised for someone who was willing to participate in experiments and maybe display negative behavior. And I got a number of people who auditioned. There were maybe 12 people who showed up. And there was one guy who was head and shoulders better than everybody else.

Ira Glass

The actor was a college student named Nick [? Fascitelli ?]. And once Will had him, he started his experiment. It went like this. He got college students and put them into teams of four. That would be three undergraduates, plus the actor who was undercover. The other undergrads didn't know that he was an actor in cahoots with the researchers. Will gave all the groups the same task to do. It was an exercise where they made some basic management decisions. And Will told them that they would be scored, and there would be a prize of $100 per person for the group that did the best. So they were motivated to do well.

Will Felps

They would work together for maybe about 45 minutes on this task. We would videotape this. And this actor, Nick, he would display one of three types of bad apple behavior. He'd either be a jerk, a slacker or a depressive pessimist. And first the jerk behavior, right? What we did was someone would make a comment, and he would say, "Are you kidding me?" He would also make comments like, "Have you actually taken a business course before?" to embarrass them or insult them.

Ira Glass

How would he do slacker?

Will Felps

Well one, he would lean back in his chair, maybe put his feet up on the desk, and then he would start text messaging a friend on his cellphone. And sometime during the experiment he would pull out a meal. So he would pull out a sandwich and a Coke.

Ira Glass

And then how did he do depressive?

Will Felps

Yeah, in that case, what he would is-- in some ways--

Ira Glass

Because I have got to say, he has only got 45 minutes. You know what I mean? It's a small palette with which to communicate depressive.

Will Felps

It was challenging for him. And he would put his head down on the table, and just look like-- I don't know-- his cat had died. That was what he said was his mental inspiration.

Ira Glass

The scripts that the actor used are included in Appendix A of Will's study. And they specify that the depressive pessimist will complain that the task that they're doing is unenjoyable and make statements doubting the group's ability to succeed. That the jerk will state that other people's ideas are not adequate, but will offer no alternatives, himself. And he'll say, you guys need to listen to the expert, me. That the slacker character will say, whatever and I really don't care.

Now the conventional wisdom in the research on this kind of thing is that none of this should have had much effect on the group at all. Groups are powerful. Group dynamics are powerful. And so groups dominate individuals, not the other way around. There is tons of research going back decades demonstrating that people conform to group values and norms. But Will found the opposite.

Will Felps

Invariably, the groups that had this actor Nick behaving in these ways would perform worse. And this despite the fact that there were in some groups people who were very talented, very smart, very likable.

Ira Glass

In fact, the actor's behavior had a profound effect. In dozens of trials, over and over, when he acted like a bad apple with a group, that group would perform 30% to 40% worse than groups without a bad apple. And even more surprising to Will was how dramatic the effect was on the way people in the groups treated each other.

Will Felps

People would argue and fight. And they would not share their relevant information. They would communicate less when he was really any of these types of bad apples. But what was eerily surprising was how these team members would start to take on his characteristics. So for example, remember we videotaped all of these. And you would see that people would start-- well, so when he was a jerk, they would be a jerk too. So they would start being a little bit insulting, or abrasive, or obnoxious. And what was really interesting is they wouldn't just do it in response to him, but also to each other. So there's a spillover effect.

Ira Glass

When Nick acted like a slacker, the spillover effect would kick in. And eventually someone else in the group would declare that the task they'd been given just wasn't important.

Will Felps

Someone would eventually say, let's just get this over with. Let's just fill in some responses and get out of here. And they would just mark down anything and then give up. What was maybe the most interesting and surprising was with the depressive pessimist. I remember watching this video where you start out, all the members are sitting up straight, energized, very excited to take on this potentially interesting and challenging task. And then by the end, they are, like him, all with their heads on the desk. So they have-- which is very strange. You're not used to seeing a group of people who are sprawled out on the desk as they do any kind of a job or a task.

Ira Glass

Well it's This American Life from WBEZ Chicago, distributed by Public Radio International. I'm Ira Glass. Today on our show we have stories of bad apples and people who are accused of being bad apples. Like for example, one family who refused to vaccinate their kids from measles, and then that led to a measles outbreak with quarantines and lots of other kids getting sick. Comedian Mike Birbiglia explains in our show today how he personally, single-handedly ruined a charity fundraiser. And Nancy Updike tells the story of a special place, a magical place, a place where no one is allowed to ruin things for anyone else.

Because in this last week as we've been putting together this show, I've really been struck at how common bad apples are. Truthfully, I've been haunted by my conversation with Will Felps. Hearing about his research, you realize just how easy it is to poison any group. Will Felps told me about this study that somebody did looking at all kinds of industries and businesses. And what they found is that the best predictor of how any team performs is not how great the best member is or what the average member of the group is like. It all comes down to what your worst team member is like. The teams with the worst person at the bottom, those teams perform the poorest. That's harsh.

And I, and I have got to say everybody in our office who's heard Will's interview-- we were talking about this earlier today. Each of us has had moments this past week where we, individually, by ourselves have wondered, am I doing bad apple stuff? Am I the bad apple unwittingly? And when I talked to Will about this, I asked him if he found himself doing this as well in his own workplace. Here's his response.

Will Felps

Yes. Yes, I have become very sensitive to this type of behavior. I catch myself sometimes. I'm just very worried now about my effect on other people. I have to say I used to tease a lot more. I used to poke fun at people and their tendencies a lot more than I do now. I thought this was fun, this was building camaraderie, that this was something that they appreciated. But what was interesting is, for example, watching these experiments with this actor, people would, for example, even laugh at his jokes when he was making fun of someone else. They would all laugh. But then afterwards, for example, when they would rate whether or not they would be willing to work on his team again, they would say, definitely not, I hated this. It was having a really negative impact. And I guess that rubbed off on me. So I just stopped being, I don't know, I stopped teasing so much.

Ira Glass

Now of course this is just one study in the laboratory. As Will points out, group dynamics in the real world-- where people work together for more than 45 minutes-- may be different in some ways yet to be studied. Though Will did see one glimmer of hope in his research. It was in one group in the study. It was the most surprising thing that happened during this research, something that completely caught Will off guard.

Will Felps

There was one group where the bad apple didn't spoil the barrel. There was one group that performed really well.

Ira Glass

And what was that group doing?

Will Felps

There was just one guy who was a particularly good leader. And what he would do is he would ask questions. And he would engage all the team members and defuse conflicts. And I found out later that he is actually the son of a diplomat. So his father, I guess, is a diplomat from some South American country. And he had this amazing diplomatic ability to defuse the conflict that normally would emerge when this actor, Nick, would display all this real jerk behavior.

Ira Glass

Seeing this diplomat's son do his thing has led Will to his next research project, which is about whether a group leader can change the dynamics and performance of a group simply by going around and asking questions, soliciting everyone's opinions, making sure everybody is heard. If that is true, if listening is all that it takes to overcome bad behavior, if listening is more powerful than meanness, sloth, or depression, it's like a trick from a children's story, a golden rule lesson that seems way too after-school special to possibly be true. That by listening to each other, trying to understand each other, we can get to the point where nobody can ruin things for everyone else.

[MUSIC - "ONE BAD APPLE" BY THE JACKSON 5]

Act One: Shots In The Dark

Ira Glass

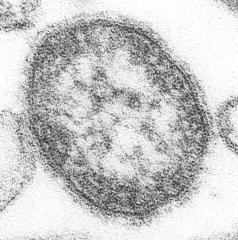

Act One, Shots in the Dark. OK, here's a situation where one family has the chance to ruin things for a lot of people. It's when they decide whether or not to vaccinate their kids. As you've probably heard, there's a whole movement of parents who do not vaccinate because they're scared of the vaccines. This is not just in the United States but all over the world. There are books. People tell their stories on daytime TV. The issue from people who believe in vaccines is that unvaccinated kids put everybody in danger. Diseases like measles-- which for all practical purposes were eradicated in the United States-- now can get a foothold because so many children in some communities are unvaccinated.

This is a touchy, divisive and bitter debate. But at least it's usually pretty abstract. It's people arguing over what might happen some day, because outbreaks of these diseases are so rare. But last winter, 12 kids came down with measles in San Diego. And it all started with a child whose parents had decided not to vaccinate him. Susan Burton tell what happened.

Susan Burton

The measles came from Switzerland. A seven year old San Diego boy caught the measles there during a family trip. He flew home to the States without any symptoms. And by the time he got sick, and doctors figured out what it was, the boy had already exposed other children. And the outbreak had begun.

News Announcer

A health warning for parents. A new cluster of measles cases at a San Diego school.

News Reporter

Already the potentially deadly disease has spread to 11 unimmunized children. Three cases are still pending. And another 60 people are in quarantine. Health officials also caution anyone who was at this Trader Joe's in Hillcrest on February 3 or at Whole Foods Market in Hillcrest on January 29 during the two hour window that the disease was in the air.

Susan Burton

Every day there were new locations-- Chuck E. Cheese's, a pediatrician's office, a swim school for babies. One child exposed a plane-load of football fans on their way to the NFL Pro Bowl in Hawaii. Meanwhile, the local news was giving everyone a panicky crash course in the disease.

News Reporter

If you are not immunized, and you're this close to an infected child, there's a good chance you can catch the measles. But even 50 feet away, you can still contract the disease. In fact, up to 100 feet away and you're still at risk of catching the measles.

Susan Burton

Measles is like a disease in a horror movie. It's one of the most contagious diseases known to mankind. It lingers in the air for two hours after a person with it has left the room. The rash makes a person look like they've grown a whole new red skin. Measles can be fatal.

And so the San Diego County Health Department immediately launched into detective work on a massive scale. They had to reconstruct the tiniest details of toddlers' lives. Who had been at what birthday party or at whose house for a play date. There were 980 exposures they had to investigate, including 160 from the plane to Hawaii, where the infected child from the flight was now being kept in isolation on a military base. The people at risk were mainly unvaccinated children, either those whose parents had opted out of the shot or babies who were too young to get the shot. It's usually given when kids turn one.

To stop the measles from spreading, the health officials decided to do something old fashioned, something that's rarely used anymore in this country. They instituted a quarantine. And this is the story of what that meant for that community of parents, about what happened when the actions of one family suddenly had a huge effect on dozens of other families and children. Hilary Chambers' daughter, Finlee, had just turned one when she was quarantined.

Hilary Chambers

I was really angry. And I felt like it impacted families financially, emotionally, on so many different levels. So I was mad, and wanted to know how did this happen. And so I did talk to friends. And I have a friend named Paige, who's one of those people that's just totally connected and knows everyone. And so she would-- and her kids weren't even involved in the quarantine. But she would call me and say, OK, so this is what I heard. It was this family was at this place, and then--

Susan Burton

Here's how one year old Finlee ended up in the quarantine. Hilary took her to daycare on a Monday morning. And one of the teachers asked, very sweetly, if Finlee had been vaccinated for measles yet. When Hilary said no, she was sent to the daycare office with Finlee in her arms. The room was packed with people. There was all kinds of commotion. And a woman from the Health Department standing there with a clipboard.

Hilary Chambers

I walked up to her and was like, what's going on? And she said, you guys can't be here right now. And I said, OK, if I take her to the doctor and get her shot today, can I bring her back tomorrow? And she said, "She is not to leave your property for the next three weeks." And my first reaction-- I laughed out loud. And I asked her if she could babysit, because it was either that or freak out, which is what I did next. I mean it was so sudden. And I was scared. And also, what was I going to do for the next three weeks? My husband and I both work. And there were people everywhere, and my daughter, and I have to be at work in an hour.

Susan Burton

At first Hilary was scared Finlee was going to come down with measles. But she didn't. And after a few days, quarantine wasn't frightening, just tedious. Hilary and Finlee would play downstairs, and then to shake things up they would go upstairs. She got regular calls from the Health Department. Someone checked every other day to make sure Hilary was keeping Finlee quarantined. It was like being under surveillance. She even felt weird taking Finlee outside to blow bubbles in the driveway, like someone would know.

Being cooped up during an epidemic used to be a typical part of motherhood. There's an argument that vaccines have actually made it possible for women to work. Hilary is a radio DJ. And during the outbreak she and her husband tag-teamed.

Hilary Chambers

My husband would wake up and go to work at 6:00 AM, and just see all his customers early. He would try and be home by noon. And we would literally high five. I would hand him Finlee. And I would take off running, be live 1:00 to 3:00, pre-tape the following morning, and on and on. It was crazy.

Susan Burton

So when you're pre-recording the following morning, you're saying, it's Tuesday morning, it's sunny and 80 degrees outside in San Diego today.

Hilary Chambers

Yeah, and this song is for so and so who just called from Rancho Bernardo. I mean you have to make it sound like it's real.

Hilary Chambers

There's The Cardigans on San Diego Star 94.1. It's Hilary. I've been getting so many calls about Jeff and Jared's thank you party. If you need the info, it's on--

Susan Burton

Even though Hilary was planning on getting Finlee vaccinated for measles, she was hesitant about it. Vaccine anxiety is pretty standard for a certain kind of over-protective mother-- and I count myself among them-- one who shops at Whole Foods and worries about chemicals in plastic and toys made in China. The shots are scary, because first of all, they're not all natural. There's no organic version of the diphtheria shot. And second of all, you have no control over them, unlike you do over the rest of what goes into your child's body.

Hilary Chambers

Free range, non-hormone meat, organic milk and yogurt, I mean we're pretty careful. Organic fruits and vegetables, the lotion that I put on her, the toys, all of that. And I can regulate that. And I have control over that. But a vaccine, it's like you're handing your child over to the doctor and saying, OK, now inject her with something that I have no idea what it is. And it's supposed to be good for them eventually and protect them. And I hope it does. But--

Susan Burton

So is there a way in which you feel like you understand the Switzerland family? You understand their mindset about the vaccines?

Hilary Chambers

No.

Susan Burton

No.

Hilary Chambers

Well, I'm sorry. I take that back. I do. As far as choosing not to vaccinate, yes. I definitely get that. I definitely understand that it's scary. And getting vaccinated, I feel like, is a leap of faith. I think the battle starts when one person's choices affect other people. So one person's-- how their child exposed all these other kids, I mean that's a really big deal. And that's just really not being a responsible member of this community, I feel like.

Susan Burton

If you've heard anything about vaccines at all, it's probably this. That there's a controversy about whether the shots lead to autism. This idea goes back about 10 years to a paper about the MMR vaccine-- that's measles, mumps and rubella-- that was published in the British medical journal, The Lancet.

That paper has since been discredited. The journal actually retracted it. Study after study confirms that the shot does not cause autism. But it's hard to shake the fear that it might be true, partly because every mom has heard stories of kids who became autistic after getting the MMR shot. There are YouTube videos.

Woman 1

Hi Eric. [BABY LAUGHING]

Susan Burton

The stories usually go like this. A mom takes her totally normal baby to the doctor. That baby gets the MMR shot. In the days that follow, he stops babbling, stops making eye contact, just slips inside himself and is never the same again.

Woman 1

Eric, hey.

Susan Burton

But saying it plainly-- there is no causal relationship between the vaccine and autism-- is asking for a fight. One of the autism researchers I interviewed was reluctant to speak on the radio. He sent me an email about a colleague who has received death threats for saying there's no connection between autism and the MMR. Real death threats, as in when the guy goes to lunch at the CDC in Atlanta he has bodyguards. All the articles I looked at online for this story are the kind that have 1,000 vitriolic comments underneath. And it's not just anti-vaccinators who are saying crazy, mean stuff. There are haters on both sides.

Sybil Carlson

I've been called a murderer, potential murder, more than once.

Susan Burton

This is Sybil Carlson. During the outbreak, she talked to a lot of reporters about how she doesn't vaccinate her children.

Sybil Carlson

Ugh, it's just over and over. I don't know how many blogs I was on where, don't I care about anybody else's children? And don't I know that the FDA and the CDC say this is all perfectly safe? And I shouldn't question them. And what am I talking about? I'm just a mom, I don't have any medical degrees.

Susan Burton

Sybil is friends with the mom who went to Switzerland. When the outbreak happened, the Switzerland mom didn't want to talk to the media. In fact, almost none of the non-vaccinators would except Sybil, who became the Switzerland mom's de facto stand in. She and her friends all got together one day. The kids played on the back deck while the mothers hammered out Sybil's talking points. And then Sybil went home and started taking calls from reporters.

Sybil Carlson

Our phone was just ringing off the hook. And my husband would be like, it's Time Magazine, it's The Today Show, it's Nightline. I mean, it was just every single day. He started laughing because these people were just calling from left and right, because, OK, she'll talk. And in the beginning, I would. I'm like, yeah yeah, I'm going to get this information out there. And I'm going to really tell them about this. And I'm just going to change people's thinking.

No. The media has an agenda. And the agenda is to take someone like me, and nitpick apart, and edit to the point where basically, you were scared. You read some bad things. So you didn't vaccinate because you didn't want your children to be autistic. But it's so much more than that.

Susan Burton

For parents like Sybil who don't vaccinate, autism is just one concern. They're also worried about autoimmune diseases and unknown long term health effects that they believe are caused by lots of different vaccines. They cite medical studies and data they suspect aren't telling us the whole truth about vaccine safety.

I'm pretty sympathetic to this stuff. When Sybil says that aluminum, a vaccine additive, is a known neurotoxin, I'm right there with her. But other things sound shakier. Still, what anyone can understand is the essence of Sybil's position, which is this. She doesn't trust the system. And you're not going to vaccinate if you don't have that faith.

That's the difference between Sybil and parents who do vaccinate. It's not that they're more altruistic. It's just that they trust the system and she doesn't. Sybil deeply believes that getting a shot could permanently harm her child. And that's scary, especially when a doctor is trying to bully you into vaccinating. She tells the story of a time she took her son to the emergency room for a dog bite, and she got into an argument with the doctor about whether her son needed a tetanus shot.

Sybil Carlson

We went back and forth. And he became very angry at me, and started chastising me for not giving my children-- "I can't believe he didn't have a pertussis vaccination. Why wouldn't you give him the whole DTaP series?" And he said, "What's your problem with the vaccinations?" I think it's probably 1 o'clock in the morning at this point. I've been up half the night. My child has been fussy and crying. And I'm sort of at this point really having a hard time defending myself.

And he really, really pushed and harped on me. And he scared me. He started using scare tactics. He's going to get sepsis. He's going to die. And they're not related to tetanus. And his agenda-- really, I could tell that point-- was he was going to get a DTaP tap into my child, because he felt like he could force me to. I did give in, which during further research I realized later even talking to my doctor, was just completely unnecessary. So that just ruined my faith even more. It sort of hit me. Wow, is it really this bad? So that was a big moment for me.

Susan Burton

Sybil gets that by not vaccinating her children, she's putting other children at risk. She doesn't dispute that. But she thinks it's unacceptable that her kids, or anyone's kids, should have to risk serious side effects from a vaccine. So until she's satisfied that the vaccine system is safer, she's willing to risk her kids getting the measles. But I spoke to another mother in San Diego who thought that choice seemed absurd.

Megan Campbell

And then the rash started getting worse. It just started spreading further down into his body.

Susan Burton

This is Megan Campbell. Her son was 10 months old when he was exposed to measles in the pediatrician's office, which he visited on the same day as the Switzerland family. Megan's baby was one of the first kids affected in the outbreak, before everyone put together what was going on. The doctor kept telling her it was just a run of the mill virus. But as the days went by, Megan's son kept getting sicker.

Megan Campbell

Come Saturday, my parents came down from Los Angeles, and took one look at him and said, your kid has the measles. Because they come from a generation that knows what it looks like. Well at that point, my son had the full rash all the way to his toes. And we would never put him down even for a nap. So like I said, my parents were down to help so that someone was always holding him, because I was honestly very afraid to put him down and lose him. I thought as long as we were holding him, then we knew his heart was beating.

Susan Burton

Megan took her son to the emergency room. When she told them he might have measles, it took two hours for them to figure out how to get him inside the hospital without exposing everyone else. Finally, they came out with a blanket, wrapped him up, and rushed him into a secure room. He dropped from 18 pounds to 12 pounds in five days.

The first thing they had to do was put in an IV. He was so dehydrated that his veins had collapsed. It took an hour and four nurses to get a needle into his wrist. Her son was screaming. Megan couldn't take it. She had to leave the room.

Megan Campbell

There were moments when I was worried that he wouldn't make it because this fever just wasn't letting up. This 106 fever and this rash that made my son look like an alien almost. And I almost wondered if he was going to look-- if he was going to be the same boy that he was a week before.

And I was a mom who has taken probably 50 pictures of my son every day since he was born. And there are no pictures of him from the moment that he got this until he was finally better, because it wasn't my son. And I never want to remember him looking that way.

Susan Burton

While Megan's son was in the hospital, news of the outbreak hit.

Megan Campbell

And I just wondered how this family who had brought this into San Diego, were they watching this television and what were they thinking? Were they thinking that they were part of something that put that child there? Or did they feel for us at all? Did they feel bad about it?

Susan Burton

Megan's son was sick for weeks. Megan and her husband both had to take a month off work. They were dumping him into ice baths when his fever spiked, constantly watching for side effects of the measles, blindness, brain swelling. When it was all over, Megan and her husband found they couldn't engage in the vaccine debate.

Megan Campbell

And I have very close friends who don't vaccinate their children. And it's just something that we can't talk about. We get too angry. We can barely speak. I feel like if I were to engage in the conversation, we might not be friends anymore.

Susan Burton

Do you think it should be a choice? Do you think people should be able to opt out of the measles vaccine?

Megan Campbell

Yes, but they have to live on an island. Their own little, infectious disease island. Don't go to the same doctors as the rest of us. Don't go to the same schools. Don't go to the same stores. Live on an island somewhere if that's the choice you want to make.

Susan Burton

But families that opt out of vaccines don't live on an island. They live all over the country, and there are more of them all the time, which is why they are of such concern to the CDC. They threaten the herd. There's this vaccine concept called herd immunity, which means that if a certain percentage of the population is immunized, it's really hard for diseases to spread. And so the most vulnerable people-- babies, people with weak immune systems, old people-- are protected. But when you fall below that percentage, suddenly infections jump exponentially.

And that's what happened here during the last measles epidemic almost 20 years ago, when 123 people died. Back then it was poor kids who weren't getting immunized, kids who didn't have access to the shots. Now it's the well-off kids of highly educated parents. So the CDC is spending a lot of time right now trying to figure out why these parents aren't vaccinating, just trying to understand their concerns. And they're working on a booklet to help doctors deliver the message better, how to reassure nervous parents. And parents nervous about vaccines are legion. A lot of them go to this guy.

Bob Sears

My experience, though, with parents, when they're making vaccine decisions, they're not thinking public health policy or public health safety. They're thinking about just their own child's health. But what can I say? I say, I understand. You have the right to make that choice.

Susan Burton

That's Dr. Bob Sears. He's one of the sons of the famous Dr. Sears, William Sears, and author of a big parenting manual, kind of a bible for crunchy moms. Dr. Bob, as people call him, is also the doctor for the non-vaccinating family that went to Switzerland. He's had thousands of conversations with parents about whether they should vaccinate. He's written a book on the subject.

Bob Sears

In my book, I actually speak to this issue using an analogy from one of the all time greatest TV shows ever, Star Trek. There's a great quote in Star Trek where Spock says, "The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few or the one." And there is no better way you can look at that than with vaccines. And Spock was saying this in the movie while he was dying to save the Starship Enterprise. And would Spock's mom have said her son made a good decision, because she had to lose her son over it? It's a big dilemma. And I honestly must say I think parents ultimately are going to choose what they view is best for the one instead of looking at what's best for the many.

Susan Burton

Have you ever used that Star Trek line in your office with a sci-fi type dad who was won over?

Bob Sears

Yeah, if there is a geeky dad. Oh yeah, of course, I like to pull that out.

Susan Burton

And does that convert a hesitant vaccinator?

Bob Sears

No. No, of course not. No. The CDC has found the same thing as Dr. Bob, that this argument just doesn't work. After the outbreak in San Diego, the CDC conducted focus groups with some of the parents involved. And one of the things they discovered was that the outbreak didn't change anybody's mind. The intentionally unvaccinated kids who got the measles came through it just fine, which proved to their parents that measles is kind of like chicken pox, not that big a deal.

On the other side, the pro-vaccinators felt ratified, like, see, it's good to get the shot because these diseases do come around. Because even though the measles connected everyone in San Diego, everybody experienced the outbreak in their own little quarantine.

Ira Glass

Susan Burton in New York.

[MUSIC - "GIRL, YOU HAVE NO FAITH IN MEDICINE" BY THE WHITE STRIPES]

Coming up, what it's like to be invited to a big charity event that you then ruin. That's in a minute from Chicago Public Radio and Public Radio International when our program continues.

Act Two: Tragedy Minus Comedy Equals Time

Ira Glass

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Each week on our program, of course, we choose a theme and bring you a variety of different kinds of stories on that theme. Today's show, Ruining It for the Rest of Us, stories of people who are accused of ruining everything for everybody else or who simply know that they are doing that. We've arrived at act two of our show. Act Two, Tragedy Minus Comedy Equals Time, specifically a long, long time between laughs.

Mike Birbiglia is the kind of working comedian who tours, and he does specials on Comedy Central, but he is not exactly a household name. Recently, he told an audience about a bad experience he had as a performer, one where he personally did not rise to the occasion. In fact, he says it was the worst show he's ever done in his life.

Mike Birbiglia

It happened this year. I was asked to perform at a charity golf tournament in New Jersey. So I woke up for this charity golf event, and I have a-- I realized recently that I'm not a good adult yet. Like I think if you're if a good adult, you plan your outfit according to what will occur when you leave the house. But I don't have that part of my brain. I'm just like, one outfit forever.

So I went and I played golf. And I brought my brother Joe. And Joe is kind of like a bad entourage member. He's never like, you the man, Mike. He 's always like, I don't know what dad would think about this. And, do you think they have any more shrimp? That kind of thing.

But we showed up to play golf and they paired us up with these two other people. It was a celebrity tournament. And the people were like, who do you think our celebrity is going to be? [LAUGHTER]

And Joe and I were like, yeah, who do you think our celebrity is going to be? And then I'm like, oh no, I think it might be me. And then I'm apologizing to these people. I'm like I'm really sorry I'm your celebrity. If you think this is disappointing for you, you can't imagine how I feel.

So I'm apologizing the whole day. And then at the end of the day, sure enough my pants are all wrinkled. And I have to be at this performance, this semi-formal banquet. And I'm like, what about one outfit forever? I thought that was a good plan. And so here's what I do. As damage control, I go to the locker room to iron my own pants. And yeah, it's a pretty good plan. And I find an iron, but I couldn't find a board. So I take off my pants. I'm just ironing them on a bench in the locker room in my underwear, which is a dead giveaway that these are my only pants.

So I'm ironing my pants. And I put them on, and I go up to the event. And this is where the trouble really begins. It's important for me, before I tell you this part of the story, to remind you that you're on my side. [LAUGHTER]

I say to the woman in charge, I go what's the format of the show? And she goes, well there are two speakers, and then you, and then a raffle. And I was like, well that's exciting, because I've never opened for a raffle. And I'm trying to stay optimistic.

And I'm sitting in the back of the room with my brother Joe, and the first speaker comes on the stage. And he's an 11 year old boy who survived leukemia. I know. He's not funny at all. [LAUGHTER] He focuses primarily on the leukemia, and everyone is crying, literally everyone is crying. I'm even crying in the back of the room for two reasons. One, the kid, and two, for me, because I have to perform comedy.

And it gets worse, because Joe leans over and he goes, this ain't looking so good Mike. [LAUGHTER] I said, I concur.

The second speaker was Hall of Fame quarterback Phil Simms. And yeah, he's got one fan here. But he's a broadcaster. And he gives an amazing, inspiring speech. And he even sprinkles in a few jokes about golf that were similar to jokes I had thought of about golf that day. It was like watching the last drops of my joke canteen drip out onto a desert of cancer. [LAUGHTER]

He gets a standing ovation, which he should have. Clearly the show is over. Surely there can't be anyone more famous than Hall of Fame quarterback Phil Simms. But wait, there was. It was Mike Birbiglia, who had no business being at this event. I know there are some entertainers who might have risen to the challenge. And I would love to be one of those entertainers, but I am not.

As a matter of fact, I have a habit in my life of making awkward situations even more awkward. I've said this before, but a few years ago I was moving a new bed into my apartment. And this woman who lived in the building opened the front door for me with her key. And she goes, "I'm not worried, because a rapist wouldn't have a bed like that." That's how she started the conversation. Now what I should have said was nothing. What I did say was, "You'd be surprised." [LAUGHTER] And there's nothing you can say after that. You're just like, see you around the building, that kind of thing.

I've thought about this a lot. And I think there's something wrong with my brain where I don't have an on deck circle for ideas. It's just, batter up. And a lot of the ideas are bad. And they're at the plate going, I don't know about this one Mike. And I just turn into this drunk little league dad. I'm like, you gonna take some cuts, son. [LAUGHTER]

As a comedian, when people laugh it's very exciting. It's a very neat thing. And when they don't, it feels like you're performing jazz. Because they're kind of bobbing their head and looking to the side. And sometimes that's OK. I'm like, I like jazz. But then I get worried, because I'm like sometimes jazz sucks. What if I'm the Kenny G of comedy? What if I think I sound like this, [MIMICS JAZZ] and in fact I sound like this, [MIMICS SMOOTH JAZZ].

So I'm on stage at the charity golf tournament. And I'm just Kenny G'ing it up. I'm just-- for 10 minutes-- [MIMICS JAZZ] just blowing that horn. And I don't want to fail. I mean that's a really important point in this story. These are good people. And I want to succeed for them, but I just can't.

And so I think to myself, why don't I cater my material to this specific event? And everyone has been talking about cancer. [LAUGHTER] I know. I'm in the future also. [LAUGHTER] [APPLAUSE] I had that thought on stage for about one second, and then batter up.

I said to the audience-- a true story-- I said I went to the doctor and they told me there was something in my bladder. And whenever they tell you that, it's never anything good, like we found something in your bladder and it's season tickets to the Yankees. [LAUGHTER] That was the response I was hoping for.

At that point, I just threw in the towel. I mean I was just devastated. I thanked the audience and apologized simultaneously, which I've never done. I was like, thank you, sorry for ruining your event. And I just walked off.

And I was so upset. And I walked over to Joe. And I go, Joe, we are leaving now. And that's when Joe said, and I quote, "Mike, I can't. They're just about to start the raffle." [LAUGHTER] "And because everybody left, my odds are amazing." And that is the worst show I have ever done in my entire life.

Ira Glass

Mike Birbiglia. That story's been recorded on one of his CDs, My Secret Public Journal, which was put out by Comedy Central and can be downloaded online at the iTunes store.

[MUSIC - "I STARTED A JOKE," THE BEE GEES]

Act Three: Disturbing The Peace Train

Ira Glass

Act Three, Disturbing the Peace Train. Nothing is too big to be ruined. Entire civilizations have been ruined. Species have vanished from the earth. And yet, something as small, as mundane, as one person's day can also be ruined. Nancy Updike has the story about the lessons to be learned from small scale ruin, and how, by trying to eradicate a problem, one can become the problem.

Nancy Updike

This story is going to end up exactly where you'd expect it to, at the entrance to a giant, inflatable large intestine. But first, a few words about bad behavior. [SOUND OF CLIPPING NAILS] This is the sound of a person clipping their nails. And this sound in public, I find, is so unexpected and distinctive that it cuts through any other sound that might be going on, dinner being served, a person giving a speech, the hum of an airplane's cabin. It's possible you're having trouble following the words I'm saying right now because this sound is so disturbing.

Public nail clipping, of course, is rare. Maybe that's why it's so memorable when it does happen. But it's part of a category of activities that isn't rare at all, that is in fact happening every day, cutting in line, parking in two spaces at once, kicking the back of someone's seat during a movie, driving on the shoulder in a traffic jam. When these things are not happening to you, it's easy to say, this is small potatoes. Who cares? But we do care. These are the stories we tell our spouses and friends when they ask how our day was. And the questions we have about these encounters are always the same, is it me? Am I alone in finding this irritating? This is bad public behavior, right? Or am I just a crank?

The only way to know for sure is to find other people who feel the same way, which brings us to Amtrak.

Amtrak Announcer

Good evening ladies and gentlemen. As a reminder, if you hear this announcement, you are in the Quiet Car. There are no cell phones permitted to use. Your conversations must be maintained at a whisper level. And no electronic devices that emit noise are permitted while in the Quiet Car. Thank you very much for your cooperation. Have a pleasant trip.

Nancy Updike

Now some of you may already have heard of the Quiet Car, but briefly what happened is this. Amtrak's East Coast route from Washington to Boston that goes through Philadelphia and New York is Amtrak's most profitable and most heavily traveled route. And about 10 years ago, a bunch of frequent Philly to DC travelers started asking Amtrak if there could please be one car on the train, just one, in which people would shut up. No cell phones, no beeping games, no yammering. Silence.

The Quiet Car was a huge hit. Amtrak added Quiet Cars to more routes and more times of day. Commuter rail lines started calling about setting up their own Quiet Cars. Amtrak trademarked the name Quiet Car.

Now if the idea of the Quiet Car doesn't appeal to you, just imagine a place where the thing that annoys you most is forbidden, whatever it is. A friend of mine hates it when people in the grocery store get bagels out of the bin with their hands instead of using the little pieces of wax paper. It would be as though she went to the grocery store and they had a special room set aside where bare hands in the bins was not permitted. Utopia.

I started traveling almost every week between Washington and New York, three and a half hours each way. And here's how it went for me in the Quiet Car. Stage one, glee tinged with self-righteousness. See? I'm not an uptight crank. This is an entire train car full of people who agree with me. I am not alone. Stage two, I am an uptight crank. And here's the kind of uptight crank I am. I started taking notes.

August 12, when you walk into the Quiet Car, people look up at you to see whether you're a member of the club. Are you someone who knows the rules and is here on purpose, or are you one of the others, some regular traveling schmo who stumbled into the car by accident, has no idea where you are, and is going to whip out your cell phone and ruin everything?

October 18, a scene in the Quiet Car. A man in a suit starts talking on his cell phone. The man sitting behind him asks him not to use his cell phone. Man in suit, "Relax buddy." Man behind him, "You relax and follow the rules." Suddenly it's mayhem. An old man stands up and says, "Yes, follow the rules. I hope you respect the rules." The man behind the cell phone talker piles on, "Respect the rules. Ignorant people don't respect rules." For a moment it seems like it could actually get violent. But it doesn't. The man on the cell phone keeps talking while he stands up and walks out. There's triumphalism in the air as he leaves. Everything I need to know about the appeal of fascism, I am learning from the Quiet Car.

January 24. I heard the loudest sound today. It was a man behind me, sighing. I had to change seats. After I change seats, someone in the row in front of my new seat gets on his cell phone. I exchange a glance with the man across the aisle, a glance that says, are you hearing what I'm hearing? We're trying to stay calm, no conductor in sight.

The man on the phone says, "Hey Mark, how are you? Hold on, let me get my calendar." I stand up and lean over the seat and whisper, politely I think, "This is the Quiet Car. No cell phones." The man makes an apologetic face, and very pleasantly gets up and leaves. Other people in the car thank me with their eyes.

March 7. The Quiet Car is not bad in and of itself, but it encourages me to see myself as a Quiet Car person. It's tribal. I am quiet and good. Other people are loud and rude. I am the beleaguered hero of my own world. The woman sitting in the row ahead of me now, in her 50's wearing movie star shades and a cute hat, talking at a level I can hear, she's the other kind of person, self- loving, oblivious, spoiled.

I'm better than that, as though my Quiet Car demeanor is a gift I give the world rather than a choice I make for my own reasons. After all, wasn't I the one laughing too loudly a couple of times at dinner last night? Do I only like to be quiet in the places I want to be quiet?

April 10. I've started putting in ear plugs in the Quiet Car. I know this is insane.

June 3. The train lost power, and we're sitting on the tracks not moving. Almost immediately, Quiet Car discipline broke down, as if the silence had been running on the same electrical system as the air conditioning. One woman got on speaker phone. Another woman started talking loudly into her phone about wine making.

I heard someone clipping their nails, no joke. Not just one stray nail, all 10, one after another.

A man start having a loud, boring conversation to escape his boredom. "Yeah, we're stuck. Can you believe it? I don't know. I just called to let you guys know. So what are you up to?"

I am sitting here shocked. I'm thinking loud thoughts at everyone around me. Is this all it takes for you to turn into savages? Where is your pride? Don't we stand for anything? We are Quiet Car people.

January 18. The Quiet Car felt like a revolution at first, an overthrowing of a bad order. But then the revolution comes for you. I got off the train in Washington one night exhausted, seven hours in the Quiet Car up to New York and back in one day. And when I walked into the atrium of Union Station, there it was, a massive, inflatable colon, a large intestine with people walking in one end and out the other, part of a colon cancer awareness campaign.

I stood there staring at it. When you're tired, anything can seem symbolic, especially something that's in your way, requiring a decision. Will you go around the giant colon and ignore what it has to say about the state of your health? Not how well you appear to the world, but the real truth of the matter. Or, will you step inside, and take a good look at all the foulness you've accumulated in your gut? I decided to go around it.

Ira Glass

Nancy Updike is one of the producers of our show.

Credits

Ira Glass

Well our program was produced today by Lisa Pollak and myself, with Alex Blumberg, Jane Feltes, Sarah Koenig, Robyn Semien, Alissa Shipp, and Nancy Updike. Our senior producer is Julie Snyder. Production help from Seth Lind and P.J. Vogt. Music help from Jessica Hopper.

[ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS]

Our web site, www.thisamericanlife.org. This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International.

[FUNDING CREDITS]

WBEZ management oversight for our program by our boss, Mr. Torey Malatia. You know I told him. I told him just the other day, why did you buy all of that Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac, and Lehman Brothers? That was just a bad idea.

Mike Birbiglia

I know. I'm in the future also.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American life.

Announcer

PRI, Public Radio International.