490: Trends With Benefits

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

OK, here's a weird fact that one of the reporters that we work with around here stumbled upon. There are these little pockets all over the country where like 20%, 25% of the people in a given county are on disability. They get government checks for disability.

For example, Hale County, Alabama. Nearly one in four working age people are not working, because they're disabled. One in four. What is going on there? Well, last fall, this reporter, Chana Joffe-Walt, who's with Planet Money, she went to Hale county to try to figure out what was going on there. And her experience there was the beginning of a six-month-long obsession with our nation's disability programs. Hey there, Chana.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Hello.

Ira Glass

So these are government checks going out every month to a fourth of the population of this county.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Of this county and other counties. There are other counties and towns like this. And the disability programs that are run by Social Security, if you could prove to the Social Security Administration that your disability prevents you from holding down a job, the government will pay you money. The average people get is about $1,000 a month. And the government also covers your health care.

Ira Glass

Oh, they cover your health care?

Chana Joffe-Walt

They cover your health care benefits, yeah.

Ira Glass

I didn't realize that.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Yeah, and in Hale County, people have all kinds of theories why this might be. Why one in four adults are on disability.

Ira Glass

And are freeloaders on the list? Is that it?

Chana Joffe-Walt

Freeloaders, fakers, people who are faking disability was always the number one theory.

John Jay

Oh I don't know. Don't get talking to me on that. But hey, there's people on disability in this town that I can write a list out is able as much to work as I am. It's going to ruin the country.

Chana Joffe-Walt

This is John Jay. He's a fit guy in his 70s. I met him in Greensboro, the county seat in Hale County. And John Jay is the head of the utilities board in Greensboro. He used to be the mayor. He sits on the board of a local bank. Basically, a guy who is used to people listening to him. And he has some theories he wanted to share.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Is it OK with you that I'm recording? I'm doing a story for the radio.

John Jay

You just have anything you want, I say. Because I'll tell anybody to the world. I'll get out there in front of the thing. But doctors, oh, whoa, my shoulder hurts and my knee hurts, doctor. I just can't work no more. Can you get me on disability? And they keep going back and back, and they'll put him on disability. And then nobody comes checks them.

Ira Glass

OK, so fakers is one theory.

Chana Joffe-Walt

So fakers is one theory. But there were actually lots of theories. I sat in on dozens of conversations like this where people were just trying to explain the high numbers to themselves. For instance, a group of ministers I met in a coffee shop were sitting around wondering if it was because of the food. It's very hard to find healthy food in Hale County. There's lots of obesity.

I heard there's something in the water in Hale County. I sat with one couple on beach chairs on their porch, and the wife, [INAUDIBLE] said, it could be because people here just live life full force. But as she was talking, her husband, Cecil, was shaking his head

Female Speaker

Like I said, we was always hard playing, hardworking.

Cecil

I don't know what that's got to do with the thing.

Female Speaker

Well, we did things to our bodies that we shouldn't have done. Drinking, smoking.

Cecil

You think people in Hale County just drank and smoked, nobody else did?

Female Speaker

No, but my age group.

Cecil

Then what's the difference?

Female Speaker

Look, you've got heart trouble.

Cecil

So I drank and smoked too.

Female Speaker

Yeah. I was just saying how we lived. That's--

Cecil

Same everywhere else.

Chana Joffe-Walt

People do smoke in Hale County. There is lots of obesity in Hale County. I think there are definitely people who are faking a disability. But the reality is much more complicated. One in four people in Hale County are disabled because of this much bigger story happening in our country overall.

Ira Glass

And that's why six months later you're still talking about disability programs.

Chana Joffe-Walt

It is. Because I feel like what I figured out is that these numbers and the growth of disability programs overall tells a story about the economy that's very different from the one we usually hear.

Ira Glass

Run me through the numbers.

Chana Joffe-Walt

OK, so the growth numbers are pretty staggering. Some of this is the Baby Boomer generation. As they age, more and more of them qualify as disabled.

Ira Glass

Because, basically when any generation gets older, they get more disabled.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Exactly. But Baby Boomers is a big generation. Still, it doesn't explain all the growth. Today there are 14 million Americans receiving payments for a disability.

Ira Glass

And how fast is this growing?

Chana Joffe-Walt

Fast. The number of workers on disability has basically been doubling every 15 years. And part of what's surprising about that is that it's happened despite all these other factors that you'd think would have exactly the opposite effect.

Ira Glass

That would take people off of disability.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Right. And that would drive the numbers down. For instance, the Americans with Disabilities Act. Remember, that's supposed to ban discrimination against people with disabilities. So you would think, in theory, that more disabled people would be working because of that.

Ira Glass

But during this period, the numbers grew?

Chana Joffe-Walt

But during that period, the numbers grew. In the 1990s, unemployment declined, crime declined, welfare was down, the economy was doing great.

Ira Glass

And the numbers still grew?

Chana Joffe-Walt

And the numbers grew during the 1990s. And there are so many more services available to people who have disabilities. We have perfected artificial hips and knees to help people walk. And we have better hearing aids to help people hear. And computer programs that read for blind people from their computers.

Ira Glass

And as all this is coming in, the disability numbers still grow.

Chana Joffe-Walt

The disability numbers have still been growing and growing and growing.

And we have barely paid attention to this. The number of disabled workers is not reported alongside unemployment data or welfare numbers or jobs numbers.

Ira Glass

Oh, that's right. You never hear these numbers on the news.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Never. So it's basically 14 million people who do not show up in any of the places that we look to to explain how things are going, to tell us how our economy is doing. And the jobs numbers, that's the thing that we pay a lot of attention to right now. The monthly disability numbers are just as big.

Since the economy began its slow, slow recovery in late 2009, we have been averaging about 150,000 jobs created per month. In that same period every month, almost 250,000 people have been applying for disability.

Ira Glass

Wait, wait, wait. It's 150,000 new jobs created every month, and it's 250,000 people applying for disability every month?

Chana Joffe-Walt

Right. Every month 250,000 people want to be on the disability programs.

Ira Glass

OK, so you're saying this massive change has been unfolding for 30 years, right? It's millions of people, hundreds of billions of dollars?

Chana Joffe-Walt

Hundreds of billions, indeed.

Ira Glass

Most of us have no idea that this is happening. And so today on our program, we're going to look at why these numbers are ballooning, why so many people are going on to disability. I have to say, this is a view of the country that upends a lot of the stories that we tell ourselves about the economy, that we hear about the economy.

From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life, distributed by Public Radio International. I'm Ira Glass. Stay with us for this hour. Chana Joffe-Walt has been trying to figure this out for a half of a year. She will be our guide. Here she is.

Act One: Act One

Chana Joffe-Walt

Hale County, Alabama is a place where people have nicknames. Where people tell you whether the man they just mentioned is white or black before they tell you his last name. And it's a place so deeply shaped by the fact that one in four adults are disabled. That fact explains daily life in town. It's why the banks are open late on the first and the third of the month, when the disability checks come in. It's why it's hard to find a parking spot on Main Street that entire week, and grocery carts are always full to the brim.

Pam Dorr moved to Hale County 10 years ago. And she didn't know the disability numbers when she arrived. So she spent her first year so totally confused about the local economy.

Pam Dorr

Well, I love yard sales, and I'm such a crazy yard saler. But I'd be on my bike the third weekend of the month or the fourth weekend of the month, and there'd be no yard sales. I'd be like really? What's going on? And then I'd notice the first of the month, every place in town had a yard sale. So it just took me a while to understand why.

Chana Joffe-Walt

If you live in Hale County, and you've got an old TV or armchair you're looking to sell, you put it out when you know the neighbors have money to spend.

A retired judge in town, Sonny Ryan, told me here is what Hale County's got-- lawyers and trees. One gets you your disability, the other keeps you breathing. Judge Ryan's court didn't hear disability cases. But he says it came up all the time anyway.

Sonny Ryan

When they would come to court, I'd say, where do you work? I'm on disability. I'd just shake my head, and I would say sometimes to the clerk, I wonder what his disability is, because he doesn't look like he's disabled to me.

Chana Joffe-Walt

When you live in a place where disability is so common, the question inevitably arises, how come I'm working, and you're not?

Sonny Ryan

I remember I had one guy in court one day. And I mean he was robust looking. And I said, just out of curiosity, what is your disability? I have high blood pressure. I said, so do I. I said, what else? He says, I have diabetes. I said, so do I. What else?

Chana Joffe-Walt

The reason this question can come up at all is that disability is basically a made up concept. There's no diagnosis called disability. There's not a blood test you can take. You don't go to the doctor and the doctor says, well, we've run the tests, and it looks like you have disability.

It is, by definition, squishy. Squishy enough that you can end up with one person with high blood pressure who's labeled disabled and another who's labeled judge.

When it comes down to it, all disability is is the label we as a society give to people who, when we hear their story, we decide they've suffered enough, and it's not fair to make them work anymore.

Dane Mitchell

I was in a 1990 Jeep Cherokee Laredo. I flipped it both ways. Flew 165 feet from the Jeep, going through 12,000 to 14,000 volts of electrical lines. Then I landed into a briar patch.

Chana Joffe-Walt

This is Dane Mitchell. He's a 23-year-old in a Greensboro coffee shop. And you just feel like, meeting him, OK buddy, you have earned it. And he's not even done.

Dane Mitchell

I broke all five of my right toes, my right hip, 7 of my vertebrae, shattering one, breaking a right rib, punctured my lung, and then I cracked my neck. So I'm on disability for that very reason.

Chana Joffe-Walt

I talked to person after person on disability in Hale County. And there were plenty of stories like this, where it's like if anyone deserves disability, it is this person in front of me.

But there was a range. There were definitely stories where it just didn't seem that clear. It seemed bad, but maybe not bad enough? It was hard to tell.

Woman

A car hit us from behind. I felt it right then. I got about five herniated discs in my back. So that's what disabled me, the herniated disc in my back. And that was the end of my work.

Chana Joffe-Walt

I sat with lots and lots of women in Hale County who told me how their backs kept them up a night. Made it hard for them to stand on the job, to lift children, to lift the elderly.

Woman

I used to cry to try to work. It was so painful.

Chana Joffe-Walt

You would cry on the way to work?

Woman

I would cry at work. I was hurting so bad, I would cry. Because they didn't allow us to sit down. Our job was to stand.

Chana Joffe-Walt

I met people who filleted fish at the fish plant with shoulder injuries, had asthma attacks, diabetes, and lots of back pain. Back pain is everywhere. The number of people suffering from disabling back pain in Alabama doubled in 10 years.

But it's confusing. I have back pain. My editor has a herniated disc, and he works harder than anyone I know. So who gets to decide this? Who decides if the story, the condition, is bad enough? Who makes that determination?

Well, in Hale County, it basically seems like there's one guy, a man whose name was mentioned in almost every story people told me about becoming disabled, Dr. Perry Timberlake.

Woman 2

He saw Dr. Timberlake, and Dr. Timberlake sent him right on to a heart doctor.

Woman

Dr. Perry Timberlake. He suggested I apply for my disability.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Who was that who recommended it?

Woman 3

Dr. Timberlake from here.

Chana Joffe-Walt

I became very curious about Dr. Timberlake. And I began to wonder if he was the reason for the one in four. That could explain it, right? There's one doctor in town, and he's running some sort of disability scam, referring every person he sees to the program.

And here is what I knew about Dr. Timberlake. He's the only general practitioner in Greensboro. He dodged me and my request for an interview. And he spent some time abroad. Nobody could tell me why.

And then after sitting in his clinic waiting room several mornings in a row, Dr. Timberlake finally agreed to see me. In the first two minutes, he explained his international travels.

Dr. Perry Timberlake

I started a project in Africa, and I ran out of money. So I came back to work.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Where were you in Africa?

Dr. Perry Timberlake

Uganda. We give people-- help them get mosquito nets.

Chana Joffe-Walt

There's absolutely nothing shifty about Dr. Timberlake. He is a doctor willing to move permanently to Hale County and serve the rural population. I was told he's one of only a few white people in town who chooses to live in a black neighborhood. Dr. Perry Timberlake, it turns out, is your classic bleeding heart. A doctor in a very poor place, where pretty much every person comes into his office to tell him they are in pain, usually back pain.

Dr. Perry Timberlake

Well, we talk about the pain and what it's like. Does it move in your legs? And I always ask them what grade did you finish.

Chana Joffe-Walt

What grade did you finish is not a medical question. But Dr. Timberlake feels this is information he needs to now.

Dr. Perry Timberlake

And rarely, rarely-- I'm not sure if ever-- they've said, well, I've finished college, four years. A lot of them have finished the 12th grade. But a lot of them have finished less than that. And just a high school education and not too many sit down jobs with that. I don't care how smart you are. You just don't get the chance.

Chana Joffe-Walt

So you think about that when you think about whether or not somebody is going to benefit from disability?

Dr. Perry Timberlake

Yeah, yeah, right.

Chana Joffe-Walt

He's asking about their education, because what the disability paperwork asks about is a patient's ability to function. And the way Dr. Timberlake sees it, with little education and poor job prospects, his patients can't function. So he fills out the paperwork for them.

Dr. Perry Timberlake

Well, on the exam, I say what I see and what turned out. And then I say they're completely disabled to do gainful work, gainful way you earn money, now or in the future. Now could they eventually get a sit down job? Is that possible? Yeah, but it's very, very unlikely.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Dr. Timberlake is saying one in four people in Hale County are disabled, not because they eat bad food or party too hard or because they're cheating. He's basically saying one in four people should be classified as disabled because they can't get a job. A fact that doesn't really seem like it should be taken into account at all. You're either disabled or you're not.

But the more I talked to people in Hale County, the more I wondered how important a person's education or job skills really were when it came to a disability. Because of this interaction I kept having over and over again, I'd listen to someone's story of how back pain meant they could no longer work or a shoulder injury had put them out of a job.

And when I said things like, what about a job where you don't have to lift people, or a job where you don't have to use your shoulder or where you don't have to stand all night long, or just simply, have you thought about other jobs that you could do, people gave me such bewildered looks. It was as if I was asking well, how come you didn't consider becoming an astronaut.

So by the time I was sitting with Ethel Thomas, I had had this conversation with so many people, that after hearing about her work at the fish plant and then as a nurse's aid until she got disability for back pain, I tried to ask the question in a different way.

Chana Joffe-Walt

In your dream world, if you could have a different job that you could do with your back, what would that be? You're shaking your head.

Ethel Thomas

Mmm. I hadn't really thought about it.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Ethel and I talked for another long while, about the town, her church. I met her husband Joseph, who's also on disability, who has nerve damage in his hands. A good 45 minutes passed. And I was getting ready to leave. And Ethel stopped me.

Ethel Thomas

You asked me a while back what would be the perfect job. I thought about it, and I said that the perfect job, it would be like I would sit at a desk like the Social Security people, and just weed out all the ones that come in and file for disability.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Wait, so what's your perfect job?

Ethel Thomas

I could sit and weed out all the ones that don't need it.

Chana Joffe-Walt

At first, I thought Ethel's dream job was to be the lady at Social Security, because she thought she'd be good at weeding out the cheaters. But no. After a confusing back and forth, it turned out Ethel wanted this woman's job because she gets to sit. That's it. And when I asked her, OK, but why that lady? Why not any other job where you get to sit? Ethel said she could not think of a single other job where you get to sit all day. She said she'd never seen one.

I brushed this off in the moment. I was getting in my car. It was getting late. And also, it just did not seem possible to me that there would be a place in America today where someone could go her whole working life without any exposure to jobs where you get to sit, until she applied for disability and saw a woman who gets to sit all day. There had to be an office or storefront in town where Ethel would have seen a job that's not physical.

And I started sort of casually looking. At McDonald's, they're all standing. There's a truck mechanic, no. A fish plant, definitely no. I looked at the jobs listings in Greensboro-- occupational therapist, McDonald's, McDonald's, truck driver heavy lifting, KFC, registered nurse, McDonald's. I actually think it might be possible that Ethel could not conceive of a job that would accommodate her pain.

It is that gap between the world I live in and Ethel's world that's a big part of why the disability program has been growing so rapidly. A gap that prevents someone from even imagining the working world I live in, where there are jobs where you can work and have a sore back, or, in her husband Joseph's case, damaged nerves in his hands.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Did you try to look for jobs that didn't involve your hands?

Ethel Thomas

What would you do? What kind of work could you do without your hands?

Joseph Thomas

I don't know. What could I do? I don't think mashing grapes is going to work here. We don't do that kind of stuff here.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Mashing grapes with your feet.

Joseph Thomas

With your feet. So we don't do that here. So that's probably all I could have done. So I don't think I know. Every job I ever be in my life, I had to use my hands to do it.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Joseph and Ethel Thomas live in a depressed town in a poor state in a national economy that is basically in the process of fully abandoning every kind of job they know how to do. Being poorly educated in a rotten place, that in and of itself has become a disability.

This is a new reality. This gap between workers who are fit for the US economy and millions of workers who are increasingly not. And it's a change that's spreading to towns and cities that have thrived in the American economy. Places that made cars and steel and batteries and textiles.

The disability programs are acting like a sponge, sopping up otherwise desperate people. This is happening so often in so many parts of the country, this shift from work to disability programs, that I have actually been reporting on it for years, and I didn't even know it.

Reporter

A small town already struggling through financial troubles just found out a major employer is shutting down. Warehouses were closed. One of the largest sawmills in the state.

Chana Joffe-Walt

This is a familiar narrative, a small town or city loses its main industry. When the mill closed in Aberdeen in Washington state, I covered it. I stood in the dead mill with a bunch of laid off workers, memorializing the end of an era. An era in America where you could graduate high school, get a job at a mill, and live a good life.

Man

We grew up together. We've gotten married. We've had children. We've raised families. Them were the best jobs on the harbor. When you had one of them jobs, you had a great job.

Chana Joffe-Walt

For NPR News, I'm Chana Joffe-Walt.

And that was it. That was the end of the story. That is always the end of the story. I had no idea what would actually become of these guys, because I, like every other reporter, showed up at the worst possible time to answer that question. The exact moment no one knows what this new reality will look like.

So a couple weeks ago, I called some of the guys I met four years ago in Aberdeen.

Chana Joffe-Walt

OK, is that better?

Scott Birdsall

I can hear you, but not real well.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Not well? OK, let me turn my volume up.

Scott Birdsall told me after the mill closed, all the worker retraining agencies from the county came in. They set up a bunch of meetings, delivered a bunch of pep talks. Scott says he went to every one, even though they all basically had the same message.

Scott Birdsall

Oh, just there's programs available and schooling and stuff like that. Retraining programs and they could help you with resumes and things like that.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Scott was 56 at the time. The last time he set foot in a classroom was 1972. And he hated school. But the worker retraining people were encouraging a forestry degree. Scott had his doubts.

And then he went to yet another worker retraining meeting at a place called WorkSource. And right in the middle of a pep talk about resumes and the value of education, one the staff pulled him aside.

Scott Birdsall

There was an older guy there that worked for WorkSource, and he just looked at me, and he goes Scott, I'm going to be honest with you. He goes, there's nobody going to hire you. He goes, we're just hiding you guys. That's all we're doing.

Chana Joffe-Walt

What do you mean hiding you guys?

Scott Birdsall

We're just keeping you, you know, out of the picture. And there's no place for you around here where you're going to get a job. Just draw your unemployment, and just suck all the benefits you can out of the system until everything's gone. And then you're on your own.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Scott says it was the most real thing anyone had said in a while. After the mill closed, Scott had a heart attack. And he did try school for a while, hated it once again.

Scott Birdsall

I thought well, you know, since I've had a bypass, maybe I can get on disability, and then I won't have to worry about this stuff anymore.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Scott was essentially taking the advice of the rogue staffer at the worker retraining office. He could have stayed in school until he was 60 in the hopes of getting a park ranger job, making half the salary he made at the mill. He made about $60,000 a year at the mill. Or, as he says, he could just accept that he was no longer useful to this economy. Didn't have the right education, right skills. He could just accept that and check out. Turns out, there is a way to do that.

Scott Birdsall

And then that's how I wound up getting into the disability thing.

Chana Joffe-Walt

And it wasn't just Scott. I talked to a bunch of mill guys who took this path. One who shattered the bone in his ankle and his leg, one with diabetes, another with a heart attack. When the mill shut down, they all went on disability. And they all, like Scott, would prefer to be at the mill. Scott says if circumstances had been different, if the entire economy had not changed underneath his feet and the mill was still open, he'd be there.

I don't know what that one rogue staffer meant when he told Scott Birdsall they were trying to hide those mill guys. But signing up for disability benefits is an excellent way to stay hidden. People on disability, the way the government counts you, you're not part of the labor force, meaning you're not counted in the unemployment figures.

An economist, David Autor at MIT, told me, macroeconomically speaking, people on disability are invisible.

David Autor

Well, that's kind of an ugly secret of the American labor market, that part of the reason our unemployment rates have been low until recently is that a lot of people who would have trouble finding jobs are on a different program. They're on the disability insurance program. And they don't show up in the labor force statistics. And so it artificially reduces the unemployment rate that we observe.

Chana Joffe-Walt

So you're saying we all already knew it was bad. It's actually worse than we think.

David Autor

It is. It's been worse than we thought for a long time. This has been going on pretty rapidly for now more than 20 years.

Chana Joffe-Walt

David Autor says disability has become a sort of de facto welfare for people without a lot of education or job skills. Except it is the worst kind of welfare program, because it includes one feature you never, ever want from your social safety net.

David Autor

Once people go in that direction, they're unlikely to come back.

Chana Joffe-Walt

The problem with using our disability programs as a sort of quiet de facto welfare system is they're not designed to help people to deal with their disabilities, to get jobs, to make increasingly more money over a lifetime. They're not there to catch you when you fall down and help you back on your feet.

Once a worker gets on disability, there are really only two ways out. You get old enough that at 65, 66-years-old, you move on to a different government program, Social Security for seniors, or you die. Those are the two ways people exit disability. Almost no one gets better. The benefits don't get you rehabilitative services or supportive technology. They just give you a monthly income.

And it's not a great income, about $13,000 a year. But if your alternative is a minimum wage job that will pay you $15,000 a year-- a job you may or may not be able to get, may or may not be able to keep, that probably won't be full time, and very likely will not include health insurance-- disability may be a better option.

Well let's just think about what that option means. You will not work. You will not interact with coworkers, get promoted, make more money, get whatever meaning people get from work. And assuming you rely only on those disability benefits, you will be poor for the rest of your life. That is signing up for disability. That's the deal. And it's a deal 14 million Americans have chosen for themselves.

Ira Glass

Chana Joffe-Walt. Coming up, we meet super nice, highly effective people who have one dream, and that is to get you-- yes, you-- onto disability. That's in a minute, from Chicago Public Radio and Public Radio International, when our program continues.

Act Two: Act Two

Ira Glass

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Our program today, Trends with Benefits. Why are so many people now ending up on disability? And it's hard to talk about all the money that the government pays to poor and disabled people without getting to a very basic question-- what should the government do for people who are not making it in this country, for the nation's most vulnerable people? We have argued about that question, answered that question in different ways at different times in our country's history.

For decades now, there have been some efforts to get people off of government checks. One of the biggest back in 1996, you may remember, President Bill Clinton signed legislation to quote, "end welfare as we know it." The idea was nudge people off of public assistance, give them job training. It has generally been seen as a big, big success, including by President Clinton. Here he is in 1998, just two years after it was passed.

President Bill Clinton

We can be proud that after decades of finger pointing and failure, together we ended the old welfare system. And we're now replacing welfare checks with paychecks.

[APPLAUSE]

President Bill Clinton

Last year, after a record four-year decline in welfare rolls, I challenged our nation to move two million more Americans off welfare by the year 2000. I'm pleased to report we have also met that goal, two full years ahead of schedule.

Ira Glass

Now the premise of that, of course, was that there are jobs for all these welfare recipients to move into and get paychecks. But over the last 30 years, that has changed. The economy has changed. Lots of good jobs have vanished. And government has not really kept up with all these changes. Has not figured out a way to address the needs of all of these workers.

And so in the place of the government doing stuff, others have stepped in, volunteers from the private sector, to see to the needs of those workers. Chana Joffe-Walt introduces us to some of these civic-minded Americans in this half of our show.

Chana Joffe-Walt

In the absence of a government answer to an enormous American labor problem, what I'm going to go ahead and call the vast disability industrial complex has sprung up. Its leaders are these guys.

Al Gemma

Disabled and can't work? Get the money you deserve. Call Al Gemma at 1-800-677-9030. Al Gemma gets results.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Lawyers.

Lawyer At Brown

Look, my law firm Brown and Crouppen has collected over a third of a billion dollars for injured people. Not million, billion. See, I fix problems.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Disability lawyers offer to fix American's problems on billboards, taxis, and aggressively on television, often with props. Gavels slammed down to show they mean business, or even better, swords.

[SOUND OF SWORD]

Sword-wielding Lawyer

Has your disability claim been denied?

Chana Joffe-Walt

There are disability lawyers who golf, who dust their desk plants while making commercials, musical lawyers.

Singing Lawyer

[SINGING] Call the Davis Disability Group. Put us on your side.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Lawyers who know how to listen.

Dr. Bill Latour

Call a lawyer who is also a psychologist. Call Dr. Bill LaTour. Disabled? Get the money you deserve.

Chana Joffe-Walt

And then there are the YouTube lawyers. One disability lawyer, one webcam. Usually the lawyer offers a handy anecdote that lets you know they're selling something you could buy.

Youtube Lawyer

I want to talk to you today about how disabled you have to be in order to get Social Security disability benefits. Well, the bottom line is you don't have to be an invalid. You don't have to be out on a stretcher. You don't have to be home wracked in pain to get Social Security disability benefits. Let me give you an example.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Almost every ad and YouTube tutorial makes sure to mention that the lawyers don't get paid unless you win. So let's talk about how the lawyers get paid for a second here. The economist, David Autor, was the first to explain this to me. If a person applies for disability, is denied, hires a lawyer, and then wins, he gets back pay for the time he waited for his hearing. Lawyers get a one-time fee, a portion of the back pay, up to 25%.

The money comes out of the disabled person's back pay. But the disabled person doesn't hand over a check to the lawyer, the government does.

David Autor

The Social Security Administration makes that payment directly to the attorney, not to the individual. So the individual gets their cut, the attorney gets their cut. So each year, the Social Security Administration makes more than $1 billion in payments directly to attorneys that have prevailed against it in front of ALJs.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Wait, so the government employs lawyers to fight the government.

David Autor

No, no. It doesn't employ the lawyers. It just pays them. It just pays the ones who win.

Chana Joffe-Walt

It pays the lawyers that win suing the government.

David Autor

Right, exactly. It pays the lawyers that defeat it.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Social Security set it up this way to encourage lawyers to represent poor clients. But I think it's safe to say the government did not expect that this financial incentive would lead lawyers to find people who had been denied disability four times, put them on television, and tell them and the viewing public--

Lawyer In Commercial

Don't give up. If you've applied and been denied, call attorney Ed Tend. He's local. He knows your doctors.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Social Security denies a lot of people, at least the first time around. Only about a third of those who apply are awarded benefits, and the rest are denied. So more and more people see these ads and appeal the decisions.

Not everyone appeals, a little more than half. And those who do have much better chances. Almost 2/3 of the time, usually with the help of representation, they win. This fact is new, the explosion of appeals and disability lawyers. And there is one firm that proudly takes credit for it, for transforming the way Americans win disability benefits.

Binder Commercial Announcer

Nobody intimidates our clients, nobody. That's one reason we're America's most successful Social Security disability advocates.

Chana Joffe-Walt

America's most successful disability advocates are Binder & Binder.

Binder Commercial Announcer

And we make you this very special promise.

Charles Binder

We'll deal with the government. You have enough to worry about.

Binder Commercial Announcer

Call us.

Chana Joffe-Walt

That guy making the promise is a cowboy-hatted Charles Binder, pointing straight into the camera. A man who has completely changed the game for disability lawyers.

Charles Binder

It's funny, when we started-- I don't think when we started, anybody else was advertising Social Security. Something, and this number you're going to be shocked by, about 90% of the people who apply for disability never got to a hearing. Because they would get denied once, and they'd get denied twice, and they'd say, well, you can't win this. And now the number of people who go to a hearing is like 95%. The people who apply who lose go onto a hearing, because they're well represented.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Binder's numbers are a bit high, but you get the picture. Things have really changed.

Charles Binder

To some extent, I take credit for that. I've created some of the problems for the government, because so many people appeal. In the old days, they had many fewer people.

Chana Joffe-Walt

When it comes to life accomplishments, it is unusual to find someone who can reasonably add "changed the US economy" to the list. Charles Binder arguably can. This is a man who is personally responsible for the transfer of billions of dollars of disability payments.

When he started in 1979, Binder and Binder represented less than 50 clients. Last year, 30,000-- 30,000 people who were denied disability appealed with the help of Charles Binder in one year. And for that work, the government wrote a check for $68.7 million.

The way Binder tells it, he is a guy helping desperate people get the support they deserve. He's a cowboy-hatted Lone Ranger fighting the good fight for the everyman. He apparently keeps a picture of the Lone Ranger on his desk.

So you've got 30,000 people denied disability who are appealing to a judge, taking their case to the courts. And on the one side, the judge has this passionate persuasive lawyer making the case that his client is physically or emotionally incapable of working. And on the other side, who's on the other side? Nobody. Nobody, really. I couldn't believe this when I first heard it. David Autor, the economist, told me with disability cases, there is no person in the room making the government's case.

David Autor

You might imagine a courtroom where, on the one side, there's the claimant and their lawyer saying, my client needs these benefits. On the other side, there's the government attorney saying, ah no, well, we need to protect the public interest, and your client is not sufficiently deserving, and here's why I think that, and so on. But it actually doesn't work like that. Because the government is not represented. There is no government lawyer on the other side of the room.

Chana Joffe-Walt

The Social Security Administration says disability hearings were never meant to be adversarial. In these courtrooms, the judges are employees of Social Security. So they have a dual role-- to represent the government and to make a fair and objective determination.

But when you talk to these representatives of the government, who also happen to be fair and objective judges, they will tell you this dual role can be uncomfortable, difficult. One judge, Judge Randy Frye in North Carolina, who hears disability cases told me he will often find himself glancing to where he imagines there should be another chair, like in any normal courtroom.

Judge Randy Frye

And there are always moments where you are concerned that maybe you missed something.

Chana Joffe-Walt

And you wish you could turn to that chair?

Judge Randy Frye

Absolutely. You would turn to the chair and say, counsel, I'm having trouble with this issue. Why does the government think this case should not be reversed?

Chana Joffe-Walt

If someone is awarded disability benefits, that person will receive an average of $250,000 to $350,000 from the government in benefits and health care over a lifetime. If you sued a company for that amount of money, even a tiny company, they would bring a lawyer with them to court. Not so with the government's disability program. The government is not even in the room.

So lawyers are making money moving people onto disability. No big surprise there. They are, you know, lawyers. But there is another group of people who are quietly doing this too. And who they're working for I found very surprising.

I want to introduce you, I want to take you inside an entire office building of these people. But first I have to explain why they exist. It has a lot to do with this guy you heard from before.

President Bill Clinton

We can be proud that after decades of finger pointing and failure, together we ended the old welfare system. And we're now replacing welfare checks with paychecks.

Chana Joffe-Walt

President Bill Clinton turned welfare checks into paychecks with the help of states. Mary Daly, an economist at the San Francisco Federal Reserve, says after the 1996 reforms, the government said states had to pay a much larger share of the cost of welfare.

Mary Daly

So states had every incentive to try to get their welfare caseloads down.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Hopefully by getting people jobs. Welfare rolls were cut in half in just a few years. And so we all assumed that's what was happening. Mary Daly wondered if there wasn't a different story.

States wanted to get people off the rolls and save money. If they couldn't get them jobs, there was another option-- disability. Disability is a federal program, so it's paid for by the federal government. In other words, if states could get people on to disability--

Mary Daly

They don't have to pay for them.

Chana Joffe-Walt

But they do have to pay for people who are on welfare.

Mary Daly

They do. And they don't have to pay for disability programs.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Mary Daly became more and more convinced this was happening. She published papers. In 2011, she coauthored a book about it. But it was just a theory.

Mary Daly

So I have my models and my theories, and I can write down what economists think. But you're never sure. You look for the empirical data, but you're never sure that what your models say actually happens.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Until Mary Daly was very, very sure, thanks to one chance encounter she had in Los Angeles. She was at a conference.

Mary Daly

It was a big hotel. And this was like the second floor ballroom type of thing, where they put the coffee break.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Mary spotted a young guy in the corner looking a little nervous.

Mary Daly

He was wearing a suit. He was probably in his late 20s. Yeah, and I just tried to be social. And I said, so what do you do? He asked me what I did. I told him what I was there to do and what kind of research I did. And he said, oh, I work for a private sector company. And our job is to sell services to states.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Specifically, this man told Mary states were hiring his company to help them comb through their welfare rolls and identify people who could qualify for disability.

Mary Daly

And that they were now helping states move people onto the federal program. So I said, really? We have this written in our book that this would likely happen.

Chana Joffe-Walt

You're like, my model predicts that this is going to happen.

Mary Daly

Yeah, I said this is what we wrote in our book. We have a diagram that suggests this will happen. But you're telling me it actually is happening. And he said, yes. Maybe one of the biggest regrets I have is that I was so surprised to run into him and to learn this that I didn't question him more.

Pat Coakley

No, it was a good conference. I believe I did speak with her outside of one of the sessions that had just ended. We were kind of out in the coffee area there and talking.

Chana Joffe-Walt

This is Pat Coakley. He works for a company called Public Consulting Group. He's the head of PCG's Social Security Advocacy management team, a subgroup of PCG that welfare reform created. PCG has competitors, but they're the biggest player offering welfare to disability services. And Pat told me business is going well. They have 17 contracts with states and counties around the country. He just signed up a new one, Missouri.

Pat Coakley

So what we're offering is to work to identify those folks who have the highest likelihood of meeting disability criteria. We will screen through their case loads. We will look to identify these individuals. It's also removing that person from the state welfare program.

Chana Joffe-Walt

And Pat says it's a win-win. For the people on welfare, disability is a much better deal. In some states, you can make four times as much on that program than on welfare.

So the first step is identifying people who might qualify. And Pat says that's actually the least time consuming part of their work,. What takes a really long time is what happens next.

Cathy

This is Cathy with Public Consulting Group.

On Phone

How are you?

Cathy

Good. How are you?

Chana Joffe-Walt

The PCG office is in eastern Washington state. It's basically a call center, head-setted women in cubicles surrounded by pictures of their kids in Hawaii, making calls all day long to potentially disabled Americans. Trying to help them to discover and document their disabilities.

Pcg Agent

All right, moving on, the high blood pressure, how long have you been taking medications for that? And the sleep apnea since about 2008. OK, I'm going to change that date for you, OK? OK, that's perfect. Can you think of anything else that has been bothering you and disabling you and preventing you from working?

Chana Joffe-Walt

The PCG agents will help the potentially disabled fill out the disability application over the phone. And by help, I mean the agents actually do the filling out. When the potentially disabled don't have the right medical documentation to prove a disability, the agents at PCG will help them get it. They will call doctor's offices, x-ray centers, get records faxed.

Pcg Agent

Sure, and that's fine. We can actually-- do have an address to Quest Diagnostics? Uh huh. I can actually try to look that up for you, if you'd like for me to.

Chana Joffe-Walt

If the right medical records do not exist, PCG will set up doctor's appointments and call applicants the day before to remind them of those appointments.

Pcg Agent

I just wanted to confirm with you that Zachary will be at that appointment. And the address, I'll give you the address when you're ready.

Chana Joffe-Walt

This is customer service in its most aggressive form. If the agents at airlines and health insurance companies worked like PCG agents, the world would be a much happier place.

These people are thorough. And once you're in their sights, they're on your side. They want you to get onto disability. And there is one simple reason for that. At the end of the PCG tour, I asked manager Leslie Jose--

Chana Joffe-Walt

And how do you get paid?

Leslie Jose

We get paid by-- our client would be like the state or the county. And so we'll get paid when we're successful with a person's claim.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Per person.

Leslie Jose

Per person.

Chana Joffe-Walt

So for every person that you get onto disability.

Leslie Jose

For every file we get on, then we would submit an invoice for that person.

Chana Joffe-Walt

In PCG's bid for the Missouri contract, it asked for $2,300 a person. Every time one of these agents succeed in winning a client disability, the state will write PCG a check. If it's successful, PCG estimates it'll save Missouri about $80 million with all the people it will be getting onto disability and off welfare. And PCG is used to being successful.

Chana Joffe-Walt

How often do you win?

Pat Coakley

We have a 70% to 75%.

Chana Joffe-Walt

So 70% to 75% of the applications that you file win awards.

Pat Coakley

Are allowed at the initial level, yep.

Chana Joffe-Walt

70% to 75% percent success rate, that is basically unheard of. Again, without PCG, your chances of winning disability on first application are about 35%. But with PCG, you take some phone calls, maybe go to the doctor, and more likely than not, you win.

Pat Coakley

Yeah, so the people are put into benefits. And they'll receive their Social Security disability income.

Chana Joffe-Walt

So you get people onto disability.

Pat Coakley

We do. We're pretty proud of the work our staff are able to do.

Chana Joffe-Walt

There was one line in the PCG contract with Missouri that stood out to me. PCG requests a fee of $1,745 for each successful foster child SSI application. What that means is if PCG gets foster kids on disability, the program called SSI, it gets paid for that too. Kids.

I heard this in Hale County that there were lots of kids on disability. I heard, actually, what you want is a kid who can pull a check. Many people mentioned this to me. And I basically ignored it. It seemed like one of those things that maybe happened once or twice, got written up in the paper, and became conversational fact among neighbors.

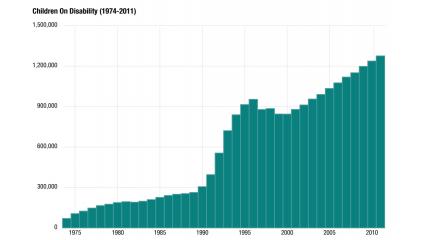

But I did look at the numbers. And the number of kids on Supplemental Security Income, SSI, for poor disabled children and adults, the number of kids is almost five times greater than it was 25 years ago. It's true. Yet another rapidly growing group of disabled Americans, children.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Hi. Hi. What's your name?

Jaleel

Jaleel.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Jaleel, how are you doing?

Jaleel

Jaleel Johnson [INAUDIBLE].

Chana Joffe-Walt

Jaleel is gap-toothed, 10, and vibrating with enthusiasm. He's excited to talk to someone new. Excited to show me his map of his neighborhood in the Bronx. Just basically psyched about everything. Even things that aren't easy for Jaleel are exciting. He has a learning disability. But the way he talks about school--

Jaleel

My favorite periods is math and science and art and lunch and recess and snack and [INAUDIBLE] and ELA and social studies and writing are my fav--

Chana Joffe-Walt

That sounds like everything.

Jaleel

--are my favorite periods. I like school. School my favorite thing to go to.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Jaleel's mom gets about $700 a month for his disability. And the idea with the program is if you have a kid with a disability, you may have to work less to help that child out. That child's probably likely to be more expensive.

When you're an adult applying for disability, you have to prove you can't function in a work-like setting. But when you're a kid, a disability can be anything that prevents you from progressing in school. And in the last two decades, there's been an explosion of kids on disability for mental or intellectual issues. It's now 2/3 of the kids on the program.

Jaleel is a kid you can imagine doing very well for himself. He is delayed. But given the right circumstances and support, it's easy to see that over the course of his schooling, Jaleel could catch up. School's his favorite thing to go to.

So let's imagine that happens. Jaleel does well in school, overcomes some of his disabilities, and he doesn't need the disability program anymore. That would obviously be great for every one, except it would also threaten Jaleel's family's livelihood. Because Jaleel's family, like a lot of kids on disability, survives off that check. Here's his mom, Nujima King. She's got two other kids, and she's not working.

Nujima King

Right now, the money that I'm receiving for him, it's extremely helpful.

Chana Joffe-Walt

So you don't have any other income other than the disability right now?

Nujima King

Just disability and a little bit of savings.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Nujima wants Jaleel to do well in school. That's absolutely clear. It is also true that Nujima's income depends on Jaleel struggling to do well in school. Depends on her kid continuing to be labeled disabled.

There are lots and lots of poor families in exactly this same impossible situation. I talked to mothers who seem to find themselves advocating something that seems completely counter-intuitive for any parent. Like a woman named Darinda Cruise. Cruise I met in Greensboro, Alabama. Darinda has told her 18-year-old son not to work, because it'll get in the way of a disability check.

Darinda Cruise

And he said he really want to work. He tell me every day he want to go to work.

Chana Joffe-Walt

But you don't want that. You want him to not mess up the disability application.

Darinda Cruise

Yeah. Not right now.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Parents get their kids on the program when they're under 18. And I guess it shouldn't be surprising, although I was pretty surprised by this-- 2/3 of them stay on disability when they become adults. They stay on a program that penalizes you if you start to do well in school or if you start to work as a grown up.

Talia Mcfadden

I'm kind of scared to work.

Chana Joffe-Walt

You're scared to work.

Talia Mcfadden

Yeah, because if I work, they'll go down on my check.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Talia McFadden is 27-years-old. She's been on the disability program most of her life. She suffers from anxiety and depression. When she was 17, she tried to kill herself. The one time Talia did have a very part time job tutoring, Social Security saw she was making some income, so they reduced her check. Talia freaked out when this happened. She quit her job.

She says her symptoms come and go, and she's just not confident she could hold down a full time job. So she doesn't want to do anything that can threaten a dependable, secure monthly check. That is incredibly valuable to her. Although, when she talks about her experience working as a tutor, sounds like that was pretty valuable too.

Talia Mcfadden

Most of my students said, I trust you. And I felt like-- I felt appreciated, you know. Sometimes the parents would say that the kid wouldn't stop talking about me.

Chana Joffe-Walt

So that must have been hard to give that up.

Talia Mcfadden

Yeah. Because it kind of gave me a sense of wanting to be and wanting to live.

Chana Joffe-Walt

It gave you a sense of wanting to be and wanting to live?

Talia Mcfadden

Yeah, because I just feel like I don't belong. Like I'm not helping to make things better.

Chana Joffe-Walt

The idea that we, as a society, should offer support to disabled children living in poverty, I haven't taken a survey or anything, but I'm guessing a large majority of Americans would be in favor of that in some form. We'd have a hard time agreeing exactly how we want to offer support. But I think there are some basic things we all agree on. Kids should be encouraged to go to school. Kids should want to do well in school. Parents should want their kids to do well in school. Kids should be confident their parents can provide for them, regardless of how they do in school. And the goal should always be for children to become more and more independent as they grow older, and, if possible, support themselves, somewhere around the age of 18.

This program stands in opposition to every one of these aims.

So somewhere around 30 years ago, the economy started changing in some important ways. There are now millions of Americans who do not have the education or the skills for the current economy. And this does not seem temporary.

Politicians certainly pay lip service to this problem during election cycles and such. But American leaders have not sat down and said, look, things have fundamentally changed. What are we going to do for these people? We need a plan.

In the meantime, the disability programs have become the default plan. Programs that, along with the associated health care, cost about $260 billion a year. And I know this is obvious, but a quarter trillion dollars? That's a lot of money. That's eight times more than we spend on welfare. In fact, it is more than we spend on welfare, food stamps, the school lunch program, and subsidized housing combined. A lot more.

Think for a minute of what we could do with a quarter trillion dollars. We could decide what we want is to expand welfare payments or food stamps. We could decide that the best plan is just to hand out cash to every out of work American. Or we could decide not to spend the money. Let everybody pay less in taxes. There are options. We just never made a decision.

Ira Glass

Chana Joffe-Walt. She's with Planet Money, which is a co-production of our program and NPR News. At the Planet Money website, you can see some really startling graphs and charts that tell this story in a way that you really can't tell a story on the radio. Seriously, some of these are kind of amazing. That is at planetmoney.com.

Credits

Ira Glass

Our program today was produced by Alex Blumberg and our senior producer, Julie Snyder with Ben Calhoun, Sara Koenig, Miki Meek, Jonathan Menjivar, Lisa Pollak, Brian Reed, Robyn Semien, Alissa Shipp and Nancy Updike. Production help from [INAUDIBLE]. Seth Lind is our operations director. Emily Condon's our production manager. Elise Bergerson is our administrative assistant. Music help from Damien Graef, from Rob Geddes.

[ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS]

This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International. WBEZ management oversight for our program by our boss, Mr. Torey Malatia. I don't know. Sitting at a computer all day, I've been having this ache in my lower back. And he and I were talking about it in the break room. And then Torey just burst into song.

Singing Lawyer

[SINGING] Call the Davis Disability Group. Put us on your side.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.

Announcer

PRI, Public Radio International.