761: The Trojan Horse Affair

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue: Prologue

Ira Glass

From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. So a while back, Brian Reed, who at the time was the senior producer of our show and he'd recently finished this great seven-episode podcast called S-Town, he was going around giving speeches every now and then about S-Town. And he was out giving a speech when a journalism student in Birmingham, England, approached him and told him a story, something that had been big news there. And there was still a mystery at the heart of it that nobody had ever solved.

And Brian decided to team up with this student. And, honestly, they have been like dogs with a bone running this down, through many twists and turns, and officials trying to avoid them or shut them down. The student, Hamza Syed, is now a former journalism student and somebody who is in all of our lives. He moved here to the United States to finish the story, which became much too big to fit into one or two episodes of our program.

So our colleagues at Serial took it over to turn into a podcast series. Sarah Koenig, the host of Serial, became their editor. The series rolled out this week. And it's spectacular, completely original. I'm very excited to play you the first installment of the show today, on our show, so you can hear what it's like. I defy you not to get caught up in the story the way that we all were. And so, with that, I'll hand things over to Hamza for part 1 of The Trojan Horse Affair.

Act One: Act One

Hamza Syed

This is my first story as a journalist. I hadn't planned for it to be my last story, but it probably will be, given what's happened in the years I've been working on this. It's about a letter that surfaced in my city and had huge consequences for Britain. This letter launched four government investigations, changed our national policy, and ended careers. It's hurt some of the country's most vulnerable children. A letter that many people who've seen it agree is ridiculous.

Tahir Alam

It's unsigned, undated.

Hardeep

It didn't look like a serious document, did it?

Razwan Faraz

It just seemed comical. Like, what the hell is this?

Sajad

I remember looking at it for some time, thinking, what on Earth is this?

Pauline

The infamous letter, was it written on parchment, in blood?

Achmad

So you're presenting me with a document that turned our lives upside down.

Hamza Syed

I first learned of the letter in 2014. I wasn't a journalist then. I was a doctor who'd quit medicine, living in Birmingham, England, making my breakfast at 1:00 PM, listening to the news, when I heard about the discovery of a secret communiqué between Muslim extremists. They were discussing a plot to infiltrate our city schools and run them on strict Islamic principles, potentially with the aim of radicalizing students.

Someone had forwarded the letter anonymously to the local government, the Birmingham City Council, but it was missing the first and last page. So it was unknown exactly who wrote it or who they were sending it to. According to the intercepted pages, the plot had a code name, Operation Trojan Horse.

I have to admit, when this story about Muslims in Birmingham first broke, as a Muslim in Birmingham, I was alarmed. It sounded possible. Kids across Britain, across Europe, were flying off to Syria to join this group called ISIS. And Birmingham has been home to quite a few terrorists. My neighbor was a terrorist, the guy who killed five people and then tried to run into Parliament with a knife. He did his planning in a flat above the Persian restaurant across the street from me.

So I wasn't surprised, watching, as over the next several months Operation Trojan Horse snowballed into a huge national story.

Newscaster 1

A number of schools in Birmingham have been infiltrated by hard-line Muslims.

Newscaster 2

Radical Muslims--

Hamza Syed

Headlines like "Islamist Plot," "Jihadist Plot."

Newscaster 2

Alleging a conspiracy by--

Hamza Syed

And the government responded with full force. The prime minister got involved, convening his cabinet to discuss the threat. The national government sent in a bunch of investigators, including Scotland Yard's former head of counterterrorism, to look into two dozen schools in majority Muslim areas of Birmingham.

Like I say, it was all very frightening. Until a few months later, when the various investigators finally started reporting their findings. They'd found no plot called Operation Trojan Horse. They'd seen no signs that anyone had been radicalized and no evidence of violence or planned violence. They didn't bring any terror charges against anyone working at the schools they'd looked into.

But despite all of that, despite finding no plot, investigators still concluded that Muslims had influenced the schools in a dangerous way. Government officials snapped into action.

Michael Gove

Things that should not have happened in our schools were allowed to happen. Our children were exposed to things they should not have been exposed to.

Newscaster 3

The fallout has been huge. Prime Minister David Cameron, as we said, is calling a special meeting of the--

Hamza Syed

Officials removed educators, revamped schools, and renamed them. They mandated all schools in the country start teaching what they termed "British values," to make kids less susceptible to extremist ideas. They beefed up Britain's counter-extremism laws by making public sector workers like teachers and doctors part of the state surveillance apparatus, to now inform on their co-workers and students and patients.

Today, the prevailing narrative of the Trojan Horse affair is that a bunch of Muslims were up to no good. There is another version of the story though. That version of the Trojan Horse Affair is that nothing happened. That these bearded Brown educators were set up. And the nation fell for it. And it's always seemed to me that there's a simple way to figure out what really happened-- the letter.

Even with all the government inquiries, no authority, none of the investigators ever figured out who wrote it. Remarkably, none of them even tried. And that, to me, seemed like a pretty glaring oversight. The reason the country was looking at these schools in suspicion, the reason they were investigating them at all, was because this dodgy letter showed up, portraying the people who worked there as nefarious plotters, claiming they were sneaking Islam into schools, like a Trojan Horse.

The letter is what put the idea in authorities' heads. So I didn't see how you could know what Operation Trojan Horse was or wasn't unless you got to the bottom of the Trojan Horse letter, who wrote it and why.

A few years later, I decided to go to school for investigative journalism. But my professor wasn't completely sold on a story I wanted to report for my student project, Operation Trojan Horse. This was investigative journalism. He wanted me to unearth something new, not rake over some years-old story.

As a doctor though, I'm familiar with the concept of a second opinion. So the night before my master's was set to start, I went looking for one.

Brian Reed

A doctor came to see me for a second opinion. One night in fall of 2017, I'm in a theater in Birmingham. After my podcast S-Town came out, I went around doing some Q&As. Afterwards, people will sometimes come backstage to chat.

And so, this guy comes in, introduces himself as Hamza Syed. He said he was changing careers to become a reporter. He was beginning a master's program in investigative journalism the next day, actually. And he wanted some advice. He was speaking fast, like I might walk away at any moment.

Hamza Syed

To be fair, I was told that I had 5 minutes with Brian Reed, after which I'd be escorted out of the building.

Brian Reed

I did not know that. Anyway, Hamza ran through the Trojan Horse story for me, elevator-pitch style. I'd never heard of it. But a guy I was with backstage, a producer I know from the BBC, he had. And he jumped in as Hamza was talking. Yeah, yeah, Trojan Horse, he said. That was a big thing a while ago. Some bad stuff went down. Muslim educators had been up to no good. But it was cleared up. Old story.

There was something Hamza said though, which afterwards I couldn't get out of my head. He kept talking about a letter which had set off this whole cascade of consequences whose origins were still a mystery. So when I got home to New York, I read the letter.

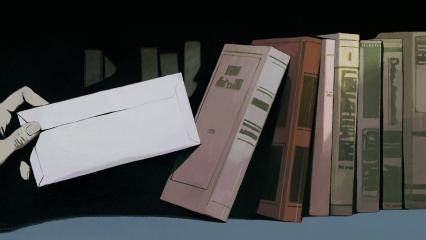

It looked like a caricature of a missive between two terrorists, filled with Islamophobic tropes about conniving and scheming Muslims. It's missing pages. Parts of it are too dark to read, like it got jammed in the Xerox machine. It instructs the recipient to destroy it after reading.

It struck me as a funky document for a government to take seriously, especially because, from what I read, the government hadn't even looked into who wrote the letter or why. There was a strange lack of curiosity about this instigating document. I thought to myself, seems like somebody should try to figure out who wrote that thing. And then I thought, well, wait, this journalism student's doing that. Maybe I ought to give him a hand.

And here we are years later, at the end of a dizzying, farcical, and enraging investigation, in which one mystery led to another, led to another, tracing this letter's path of destruction across multiple continents--

Hamza Syed

--in defiance of many unhappy officials and some aggressive attempts to shut our reporting down.

Brian Reed

From Serial Productions and The New York Times, I'm Brian Reed.

Hamza Syed

I'm Hamza Syed.

Brian Reed

Presenting to you the most elaborate student project ever, this is The Trojan Horse Affair.

Hamza Syed

I got the call from Brian while I was in class. My phone started ringing from a New York number. I asked my professor if I could take it. He said no. I asked if I could go use a toilet. He said yes.

I answered. And Brian told me he wanted in on my investigation, but that I would need a producer. I said, yeah, sure, all casual. I had no idea what a producer did. Soon, he started getting in touch, with missions for me to complete. The first one, he'd secured a recorder for me in Birmingham and said there was something I had to do.

Brian Reed

It was supposed to be a basic, bread-and-butter assignment, go record a meeting. Hamza had seen an event advertised called Trojan Horse, the Facts, where some of the educators who'd been accused of carrying out the plot would be speaking publicly.

They insisted the Trojan Horse Affair was just an Islamophobic stitch-up. The event hashtag was #TrojanHoax. And they were trying to clear their names. They'd never gotten their lives back on track after the story had died down. They'd lost their jobs and been made into pariahs by the national media.

But afterwards, Hamza calls me and says when he showed up at the spot, a community center, at 5:00 PM, the receptionist told him--

Hamza Syed

It's been canceled. The event's been canceled.

Brian Reed

Did they give you any-- well, wait. Did they give you any other information? Like, what--

Hamza Syed

No. They just said it's been canceled. And that was it. I said, no, this is-- you know, I spoke to the event organizer a few days ago. They said, yeah, it got canceled today. So I felt like an idiot, to be honest. Because I'm standing there with this big mic stand that looks like a fishing rod. I got my box of equipment.

This can't be a good omen, I thought, to mess up your first journalism assignment. But then more people started showing up, confused like me. Until a man in one of those safety vests swings around the corner, tells us to follow him, and takes us up the street to a wedding hall where everyone was gathering instead. It's a lot of people, maybe over 100. And, as I explained to Brian, while I'm setting up the microphone--

Hamza Syed

--I start catching all the whispers, in terms of what happened. And it turned out that the original venue had received phone calls from the national newspapers, specifically this guy, Nick Timothy.

Brian Reed

He's like a reporter or a publisher? Or what is he?

Hamza Syed

He's a columnist, I think, for The Telegraph.

And not just any old columnist. Nick Timothy used to be the chief of staff to the prime minister. He was essentially Teresa May's right-hand man. I spoke to the guy who ran the community center, who told me Nick Timothy had actually emailed, not called. He wouldn't let me see the email. But according to others at the meeting, the implication was, if you hold this event, I will associate you with extremists in the newspaper. And the community center pulled the plug.

Nick Timothy denies contacting the community center and says he doesn't know who did or what they said. But he wrote a triumphant column about the planned meeting which I'd missed because I was on YouTube all day watching instructional videos on how to use my recorder, in which he noted, quote, "When the Daily Telegraph discovered this and contacted the owners of the venue, they rightly cancelled it." He went on to suggest the event organizers were extremists and described the proposed meeting as, quote, "a shocking attempt to deny the Trojan Horse scandal," and, quote, "the people behind the Trojan Horse are trying to do it all over again, and right under our noses."

[APPLAUSE]

Announcer

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. And welcome to Trojan Horse or Hoax, the discussion and debate.

Hamza Syed

So here they were, the teachers and school volunteers allegedly behind Operation Trojan Horse, along with their defenders, academics and activists and an educational barrister and a union leader, packed in this wedding hall instead.

Salma Yaqoob

I am really, really concerned that simply holding a public open meeting like this becomes controversial. Just the fact we are holding this meeting seems to be an act of resistance right now.

Hamza Syed

The people at this meeting called for an inquiry to correct the record on the Trojan Horse affair. They believed the government had set them up. So the fact that a former chief of staff to the prime minister, Nick Timothy, went out of his way to attack a grassroots event at a community center years after the Trojan Horse Affair, it just reinforced their suspicion-- and mine, quite honestly-- that there was something dodgy that authorities were still keen to hide.

Parent

And then it was like a witch hunt. Heads were rolling this way and that way.

Brian Reed

Hamza sent me the recording of the meeting. I listened to it. And I was interested to hear that one of the people who got on stage and spoke was the man named repeatedly in the Trojan Horse letter as the mastermind of Operation Trojan Horse, the plot's alleged ringleader, a longtime school volunteer named Tahir Alam.

Tahir Alam

I've never been a danger to anyone. I've never hurt anyone. I've never had any police case against me or anything of the kind. I wasn't running a plot. We are very proud of what we did in these schools. I do not regret nor apologize for anything that I've done. There was nothing clandestine, hidden, or sinister about what we were doing. We were very open and very transparent.

Brian Reed

So when I landed in Birmingham to begin reporting, that's who we decided to go to first, Tahir Alam. We figured, we're looking to find the source of this mysterious letter. Might as well start with the guy it outed as an extremist plotter.

Brian Reed

Is this about to be the first radio interview you've ever done?

Hamza Syed

Yeah. I need to be schooled beforehand, mate.

Brian Reed

What do you mean? Like, how so?

Hamza Syed

Well, I mean, if this is me flying solo, I would be like, well, whatever. I'll just do it my style, you know. But this is--

Brian Reed

And what is your style? Do you have a style?

Hamza Syed

I don't know. I feel like I'm a lot--

Brian Reed

How many of these have you done?

Hamza Syed

None.

[LAUGHTER]

But I have an idea in my head of what my style could be. I think you're a lot more sensitive than I am, put it that way. Do you know what I mean? Like, you're--

Brian Reed

I'm the more sensitive one?

Hamza Syed

I think so. Don't you think so?

Brian Reed

I don't know. I don't know you that well.

Hamza Syed

I wonder what he'll be wearing.

[DOORBELL]

Hamza Syed

Salaam, Tahir, salaam.

Tahir Alam

Hello.

Brian Reed

Ill-fitting button-down shirt, khakis.

Tahir Alam

Welcome.

Hamza Syed

Thank you.

Tahir Alam

You're going to be in that room there.

Hamza Syed

This room?

Brian Reed

We kick off our shoes. He shows us to a room at the front of his place.

Tahir Alam

Sorry you have to sit on slightly uncomfortable chairs there.

Brian Reed

Hamza and I squeeze behind two school desks meant for children. There are protractors lying around, a whiteboard with sketches of geometric shapes, a creative writing workbook titled "Descriptosaurus." Tahir's converted this room from his garage into a tiny makeshift classroom, where it appears he tutor students quietly. Because one result of the Trojan Horse letter is that the government has banned him from ever volunteering or working officially in schools again.

Tahir's in front of us in his office chair, confident, erudite, framed by his bookshelf filled with texts about Islam and British history. I pull a copy of the letter out of my backpack.

Tahir Alam

You know, it's a completely anonymous letter, undated, claiming that there is a plot to take over and Islamize the schools in Birmingham, led by Tahir Alam, which is myself. But I speak from a vantage point where I actually know the truth. I know the reality.

Brian Reed

Tahir denies being an extremist. He denies engineering a plot. He says the reality is that, rather than corrupting schools as a radical conspirator, he, a first generation immigrant from a poor Pakistani family, was responsible for one of the most miraculous school turnarounds in British education. Until, he says, the letter arrived and destroyed him.

Hamza Syed

The story of this turnaround, it's not a secret. It's one Tahir shared with journalists before, not that it's done much good, in terms of clearing his name. But this back story does explain why the Trojan Horse letter was so persuasive. Because, Tahir told us, some of what was in that letter was true.

Tahir begins the story one night in 1993 when he's watching TV, and a show caught his attention.

Tahir Alam

I just happened to be just lying on the sofa, really, and the program came on.

Hamza Syed

It was a documentary, part of the BBC series, Panorama.

Tahir Alam

9 times out of 10, I would switch to something else. But I was just sitting there and I started watching.

Documentary Presenter

Britain's new underclass is Asian and it's Muslim. A once tightly knit community is now in crisis, with drug abuse, crime, and family breakdown on the increase.

Tahir Alam

And the title of this documentary was Underclass in Purdah.

Documentary Presenter

In tonight's Panorama, we investigate an underclass in Purdah.

Tahir Alam

Purdah meaning cover, meaning a veil, if you like. "Underclass in the Veil," yeah?

Documentary Presenter

In tonight's program, we lift the veil on this new underclass. A report from the--

Hamza Syed

The documentary opens with shots of Brown men skulking around dark cobblestone streets in a Muslim neighborhood, in what the correspondent calls the Muslim ghetto.

Documentary Presenter

At night, it doubles as the local red-light district.

[SIREN]

It's a seedy world of vice and illicit drug dealing. Lurking in the shadows is a new Manningham phenomenon, the Pakistani pimp.

Hamza Syed

He's like a regular pimp, but in a kurta.

Part of the documentary takes place in Tahir's neighborhood in Birmingham, called Alum Rock, on the east side of the city. It's one of the poorest areas in England, and it's majority Pakistani and Muslim. If you're not from Birmingham and you're not Brown, you may have heard that Alum Rock is a great place to find a terrorist. If you're not from Birmingham and you are Brown, you'll have heard Alum Rock is a great place to find a wedding dress.

Admittedly, this BBC documentary is racist in a '90s TV kind of way. But it had a big impact on Tahir because, amidst the awkward Brown gazing, some truly sobering facts emerge. The presenter reports that Pakistani Muslims are incarcerated at disproportionately high rates. She says they have some of the highest rates of joblessness. They're suffering from devastating health issues, terrible housing, domestic violence, with one underlying cause of it all, a lack of education.

This is the number I found more shocking. About 20% of white students were leaving school without any qualifications, meaning they failed to pass exams that would essentially be the equivalent of a high school diploma in the US. And that rate, 20%, was roughly the same for most people of color as well.

Documentary Presenter

But for Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, an astonishing 50% hold no qualifications whatsoever.

Hamza Syed

50%, half of us, were basically failing school. That hit Tahir hard.

Tahir Alam

That the extent of education failure was so bad that we were at risk of creating an underclass of Muslims who were basically uneducated, prone to crime and unemployment. So I kind of sat there, and it made me feel guilty, actually. Guilt because I was one of the few people who made it-- from my family, one of the first ones to make it into university and to have a good job, and so on. But there was also a sense of humiliation, really, because I was from this community.

Hamza Syed

Tahir's family brought him to England in the '70s when lots of people from Kashmir were moving here, largely because the British designed this huge dam that flooded swaths of land and displaced tens of thousands of people. And one solution the Brits got behind was to invite displaced Pakistanis over to England so they could improve the British economy by working in British factories and mills.

Which is what Tahir's dad did. Tahir arrived in England as a nine-year-old who didn't speak any English and wouldn't become fluent for several years.

Tahir Alam

I knew one word of English only, which was F-O-R-D. I mean, I don't know X-Y-Z, but I know F-O-R-D. That's it.

Hamza Syed

I can relate. I couldn't speak any English when I first came here.

Tahir Alam

All right.

Hamza Syed

I couldn't even speak "Ford." I was just, like, mute. "Football," that's what I knew, "football."

Tahir Alam

That's right. So that's how you arrived here. And the first school, when I came here, we arrived--

Documentary Presenter

--potentially the biggest ethnic group in the country is growing up angry and alienated from white society.

Hamza Syed

Now Tahir watched as the documentary captured the next generation, Pakistani kids who were born in Britain, being educated in state schools, still struggling to read, not able to recall basic English words.

The camera cuts to a park in Birmingham. It looked to Tahir like Ward End Park, which is right across from where he went to school in Alum Rock.

Tahir Alam

I recognized the park because we used to go and play there. And then I saw some children. And I said, oh, that's our neighbors' children. I recognized the kids, yeah, even though it was from a distance. But I recognized who the kids are.

Documentary Presenter

We filmed an encounter with two Asian lads in a park in a Muslim quarter of Birmingham.

Hamza Syed

These Asian lads-- we use "Asian" to mean South Asian, by the way-- they're skipping school. And Tahir knew which school they were skipping. It's the one he'd gone to as a kid, right next to that park, Park View School, another majority-Muslim school with miserable academic results. It's a secondary school, ages 11 to 16. It was a school where Tahir had done well enough to make it to college and then university before getting a good job in telecommunications. The documentary made him realize how rare his success was and how little he'd done with it.

Brian Reed

So Tahir decided to do something. He started a tutoring program for kids in the neighborhood. But what he was really interested in was volunteering at his old school, Park View, on what's known as their governing body. In England, a governing body oversees how a school is run, like a corporate board does a company. It's sort of like a school board in the US, except it's specific to one school. They can have a lot of influence.

So anyway, Tahir says one afternoon a couple of Park View parents he didn't know knocked on his door. We hear you're interested in becoming a governor, they said. It was like they'd read his mind. Though, actually, Tahir had been talking about wanting to be a governor at a recent wedding, and these parents got wind of it.

Resentment and frustration had been festering for years among parents in Alum Rock, who'd been trying and trying to get the authorities to do something about the dismal schools. These parents at Tahir's door had joined the Park View governing body in an attempt to make a change. But they didn't speak fluent English and hadn't gone to university. Tahir was a professional with a degree who still lived in the neighborhood.

We'd love to propose you, they told him. And with that, Tahir found himself at the next governing body meeting of Park View School, being voted in not only as a member but as the chair.

Tahir Alam

So that's when I became a governor, on the 7th of January, 1997.

Brian Reed

You remember the date?

Tahir Alam

Yeah, well, I was to remain there for 18 years.

Brian Reed

When Tahir started, Park View was one of the worst secondary schools in the country. Only 4% of students were passing, 4%. The National School Inspection Agency had recently placed the school into special measures, the lowest possible ranking, an emergency status, basically, meaning Park View was in danger of being shut down.

There were brawls breaking out in the schoolyard. On a tour of the building, Tahir saw vandalized bathrooms with stalls missing locks and toilets missing seats. But where Tahir really trained his focus was on the complacent teachers and administrators.

Tahir Alam

We initially just started by saying that, obviously, children should be achieving higher, that the achievement was not acceptable, and the fact that the school was to blame for the failure.

Brian Reed

This statement, so obvious to Tahir, that the kids in Alum Rock were as capable as kids anywhere, was met with massive resistance.

Tahir Alam

It was very difficult getting the school to accept that they were the problem. People didn't want to accept that because they'd been blaming the community for maybe two decades. They had such a low expectation of children.

Brian Reed

One thing Tahir noticed early on was that the staff of this school with nearly 90% Pakistani students had only one full-time Pakistani Muslim teacher. So Tahir begin searching for more Muslim staff and governors. He gave presentations, held workshops. He became a fixture at events around East Birmingham, standing behind his little table or booth, evangelizing for people to get involved in their local schools.

Moz Hussain

I loved it. [LAUGHS] I loved it with the children because I felt as though I could make a difference.

Brian Reed

This is Moz Hussain, the first Muslim teacher Tahir hired. He taught math.

Moz Hussain

I could use my language, my background, my understanding of where they come from, to make a difference. I knew their families.

Brian Reed

Moz can point to a specific moment, by the way, when he decided to go into teaching.

Moz Hussain

There was a Panorama program. It's called An Underclass in Purdah.

Brian Reed

Powerful segment.

Hamza Syed

Moz Hussain says from the very beginning he encountered serious prejudices among the mostly white staff.

Moz Hussain

I had a group of children come to me. And they said, look, there's this one teacher in school. He always calls us Pakis. He's calling us Pakis. He's doing it in a jokey way, but we find it offensive. They're not able to tell anyone else, but they're telling me that, look, he's swearing at us.

Hamza Syed

That's a slur in any context, but especially shocking for a teacher to say to Pakistani students. Moz told them, I think the best thing to do, have your parents write the school. He talked them through the procedure for doing that, in case their parents didn't know. He says eventually the school looked into the teacher's behavior.

Moz Hussain

And while they were investigating, he resigned. And he gave his final leaving speech in the staff room. And goes, it should be our culture dominant in this school, not the kids. And he finished off with the words, the West is the best. And all teachers clapped. All teachers clapped.

Brian Reed

The racism was pervasive. Razwan Faraz, a former governor and math teacher, says at one of his first governing body meetings he was shown a list of places the students had been given work placements through a program at the school. And it was all restaurants, supermarkets, clothing stores.

Razwan Faraz

And there was no surgery, doctor surgery, or law firm, or anything like that. And I said, how is it that-- did the children decide these?

Brian Reed

And Razwan says the vice chair told him--

Razwan Faraz

Well, their parents want them to go and become doctors, and engineers, and et cetera. But reality is, these kids will become taxi drivers, shopkeepers, so we've got to prepare them now.

And for a good while I was struggling to process what he was saying. This is me, a Brown person, and a Muslim, and he's saying to me that they deserve to have these kind of jobs.

Brian Reed

This is this community's role in society, basically.

Razwan Faraz

That's right.

John Brockley

We just failed the kids. We just failed the kids. And didn't even feel bad about it. Didn't even-- we didn't. Didn't even feel guilty.

Brian Reed

John Brockley was one of the non-Muslim teachers at Park View. He was a math teacher who'd been there since the '80s. He was frank with us about the bigotry that he and his colleagues held towards the students and their families.

John Brockley

We thought that we were a superior culture. And we looked down. We looked down on these people who didn't know about education.

Brian Reed

You're talking about yourself here?

John Brockley

I'm talking about myself, but I'm also talking about many of the people that I worked with.

Brian Reed

The teachers attitudes are documented, by the way. A former headteacher of Park View-- a headteacher is what we Americans call a principal-- did a master's thesis while he was at the school, for which he collected opinions from the staff, including from John, as to why Muslim children were drastically underperforming compared to their peers.

In the thesis, teachers say the kids parents are ignorant, wrongly claim the students don't speak English. The teachers try for a while, one teacher said, but end up feeling like, who gives a damn. That's a quote. It makes John cringe to think back on it.

John Brockley

It's only when you when you move away from a situation like that that you can realize how awful it is. I don't normally think about this sort of thing because it's too embarrassing.

Tahir Alam

Once we created the shift in the belief of the teachers, then the job became much easier.

Hamza Syed

Tahir says by the early 2000s, Park View was changing. The school began taking basic but transformative steps, setting individualized achievement targets for each student that followed them from year to year, and preparing students for qualifying exams which, amazingly, hadn't happened before. School started awarding trophies for good marks, inviting parents to ceremonies when their kids did well.

Tahir and the governor's hired a new headteacher, a non-Muslim woman from a girls' school, who embraced Park View's new aspirations. Test scores started to rise. Students were heading to college. Park View's reputation was turning around. But there were other changes Tahir instituted at Park View which, later, officials would view as suspect, changes that investigators would point to as the trademarks of Operation Trojan Horse. That's coming up.

Ira Glass

Indeed it is, when Hamza and Brian return. That's in a minute, from Chicago Public Radio, when our program continues.

Act Two: Act Two

Ira Glass

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Today on our program, we are playing part 1 of the newest podcast from our sister company, Serial Productions. The show is called The Trojan Horse Affair. And we pick up with Brian and Hamza where they left off.

Brian Reed

You don't get labeled the leader of an extremist conspiracy simply by raising test scores at your neighborhood secondary school. The main accusation against Tahir Alam, the overarching assertion of the Trojan Horse letter, which the government supported and which has defined Tahir's reputation since then, is that he was Islamizing schools.

This is not a word I'm particularly fond of, "Islamize," because Islamize in relation to what, some assumed non-Islamic baseline? Has this story been Islamized by Hamza's involvement?

Hamza Syed

Yes.

Brian Reed

It's a word that isn't inherently negative but gets used that way. Anyway, that's what the letter said Tahir was doing, Islamizing schools. And, funnily enough, it's also what Tahir says he was doing.

Tahir Alam

We were valuing the cultural and the faith background of the children. And we were allowing that to be expressed, if you like. We catered for children so they could perform their daytime prayers if they wanted to. We made a prayer facility available for them in a room.

Brian Reed

Religious accommodations like this are legal in British schools, by the way, whether they're explicitly designated as a religious school or not, which Park View wasn't. It was the equivalent of a regular public school in the US.

Tahir Alam

And since 98% of the children happened to be of the Islamic faith background, we obviously are catering for the constituency that the school serves, in line with the regulatory requirements.

Brian Reed

Tahir ascribed to an educational philosophy that, the way he and other Park View staff talk about it, reminds me of Afrocentric or Black Excellence schools in the US, that students will do better academically when their schools incorporate and celebrate who they are. And there's research that backs this up.

So, under Tahir's leadership, Park View allowed students to pray if they wanted. They installed facilities for wudu, the ablutions you do before prayers. They celebrated Ramadan and altered the schedule during that month to facilitate fasting. They served halal food.

Tahir Alam

And I felt that, you know, this was our school. I mean, we were proud to say that this is our school. We wanted our children to say that this was their school and that they were proud of it.

Hamza Syed

In the wake of the Trojan Horse letter, government officials would declare that the way Tahir and his colleagues were running Park View school had undermined, quote, unquote, British values, that they were limiting the children's ability to thrive in modern Britain. Which is an interesting charge to bring against Tahir because, I have to say, I haven't personally met an English Pakistani more confident that he's British than Tahir.

Deciding whether or not to call yourself British is a fraught and personal thing for us. Speaking for myself, even though I came to England when I was 8, and became a British citizen with a British passport, even though I have a British education, went to British University, worked for Britain's National Health Service, I didn't call myself British. I was never precious about nationality, so I didn't really care what I was called. But sure, I'd also picked up on the subliminal messaging that in order to be proper British you had to be white.

Tahir, on the other hand, not only calls himself British, but does so proudly. I got to talking to Tahir about this one day. He and Brian and I were getting tea at my favorite chai shop on Alum Rock Road.

Tahir Alam

Well, this is the hangout.

Hamza Syed

And as we sat outside in one of the main thoroughfares of Islamic Britain, around the corner from where Tahir grew up with double-decker buses passing by sweet shops and fabric stores and halal chippies, I told him my reason for why I'd finally, only recently, started calling myself British.

Hamza Syed

So for a long time, I never called myself British.

I was about 30. I had been reading a book about the British empire. And I learned how rich India, which at the time included Pakistan, was, according to some economists, before the British took control.

Hamza Syed

And I believe the statistic is, roughly it controlled about the 24%, or something like that, of the world's economy at the time.

Tahir Alam

Yeah, 23% of the world's economy.

Hamza Syed

Right.

Tahir Alam

It was the richest nation in the world.

Hamza Syed

Right.

24% of the world's economy is roughly what the US controls today. I know this is somewhat of an apples and oranges comparison because the world wasn't organized into a globalized economy back then. But it does show how rich India was in relation to other countries at the time. When the British left the Indian subcontinent after some 200 years of economic exploitation, India and Pakistan were among the poorest nations in the world.

I didn't learn this stuff in school because Britain's colonization of a quarter of the planet is not compulsory part of the national curriculum, which is why I only discovered it as an adult, that so much of the wealth I saw in Britain was actually extracted from the place I come from.

Hamza Syed

And so, from that point onwards, I've started calling myself British. I was just like, well, I'm British. I own this country. This is my money with which you have raised everything around me.

Tahir Alam

Yeah, so, I mean, that's very similar to the position I am arrived at.

Hamza Syed

Except, for me, proclaiming I'm British is somewhat of a finger in the eye. For Tahir, it's sincere. It also came to him later in life. He says he was at an event held by a British Muslim organization. And they began saying, very clearly, you're never going back to Pakistan. Your children are never going to move back.

Tahir Alam

It's not going to happen.

Hamza Syed

That's what you had been thinking up to that point.

Tahir Alam

Yeah, because our parents spoke like that to us. Our homes are in Pakistan. We are Pakistani. Our parents spoke to us like that. My father never told me we are British because that's not what he felt. He lived in Pakistan most of his life. Why would he say that?

Hamza Syed

The people at this event were saying, you live here now.

Tahir Alam

We were part of this country, and that it was important, as Muslims, we should bring benefit to this country. So ever since then, I've been kind of dissing the idea that we are other, that we are outsiders, that we don't belong here. Islam is part of Britain. It's not alien. I don't accept that. Can you see? So this is why--

Hamza Syed

So for Tahir, not only was incorporating Islam into the school an academic strategy, it was also a British value.

Former Student 1

It was really nice for me that--

Former Student 2

It was during school?

Former Student 1

--I'm doing something at home, and now my school is helping me do it.

Former Student 2

Yeah, like, I didn't want to have a different life at school. If I'm praying at home, I want to pray at school too because--

Brian Reed

These are two students who graduated from Park View in 2014. We're not using their names because such is the stink of the Trojan Horse scandal, they don't want potential employers to know where they went to school. They actually keep it off their resumes.

When Hamza and I met them four years after they graduated, they were both studying law at university, some of the first in their families to go on to higher education. They've been best friends since school, the kind of friends who don't need words to communicate.

Former Student 1

Are you talking about-- um, yeah. I don't know if I should--

Former Student 2

Oh, that.

Former Student 1

We're telepathic, basically.

Former Student 2

Basically.

Brian Reed

The students told us about these assemblies they would have in the mornings, which included religious teachings and sometimes prayer.

Former Student 2

So there was this one incident--

Brian Reed

This is something that, as an American, made me do a double take when I first heard about it. The idea of teachers in a public school leading prayers during assembly is not normal to us. But in Britain, there's no separation between church and state. The queen is head of both. So not only is prayer allowed in schools, some form of worship is legally mandated in all schools that are publicly funded.

Schools don't always adhere to this, but students are supposed to take part in what's called a daily act of collective worship. By default, it's supposed to be broadly Christian in character. But schools can apply to change it to other faiths, if that better suits their students. Which is what Park View did, it got approval for its worship to be Islamic.

The students told us, at Park View's assemblies they would sit in the main hall and a teacher would tell parables or lessons, usually from Islam, but other faiths too.

Brian Reed

Do you guys remember actually learning things in these assemblies? Or did they make you think? Or were they just kind of boring teachers blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, like--

Former Student 1

No, they would make us think.

Former Student 2

I really enjoyed those assemblies because I didn't learn this from anywhere else.

Brian Reed

They still remember this one assembly all these years later, about charity.

Former Student 2

Talking about charity, and they say when you're giving charity, put your hand in your pocket and take out. Don't look at how much you're giving. Just put it in. Don't count what you're giving and what you have left because when you give, you receive tenfold.

Former Student 1

Yeah. And charity does not make you poor. Quite literally, sometimes when I, like, see somebody who is asking for money and things like that, I'll put my hand in my purse.

Former Student 2

And take it out.

Former Student 1

I'll take it out and I don't look at what's in it.

Former Student 2

I do that all the time.

Former Student 1

Just because I remember that one teacher. He literally said it like that.

Former Student 2

Like that. Give so that your left hand doesn't--

Former Student 1 And 2

--know what your right hand gave.

Former Student 1

Yeah. Yeah.

Former Student 2

Yeah.

Hamza Syed

When Tahir became chair of Park View's governing body in 1997, 4% of students were passing. By 2010, that number was 71%, a seventeenfold increase.

Tahir Alam

We had not changed the children. We had not changed the parents. But, slowly but surely, we took the results so that they were consistently in the 70s, which means the school actually is kind of guaranteeing an outcome.

Hamza Syed

Park View was now actively preparing its students for the eventuality that their academic success would lead them out of East Birmingham.

Former Student 1

Something that a lot of teachers said to me, you live in a bubble.

Hamza Syed

Again, the former Park View students.

Former Student 1

And I was like, what do you mean? They were like, you live in an Asian community. You go to an Asian school.

Former Student 2

Yes.

Former Student 1

You're very safe. You don't know what it's like to branch out. I remember, we learned about the population and how it's divided in UK. And I think it was something like 2% of the population in the UK is Asian. And I was like, whoa, only 2%. I was like, 2%? How is it 2%? Like, everybody I know is Asian.

Former Student 2

Every person that I've come across is probably--

Former Student 1

Yeah.

Former Student 2

How is that possible?

Former Student 1

So it was so odd.

Hamza Syed

The UK is actually 2% Pakistani, 7% Asian. The point being, there was a vast majority of the population that these students and their classmates were not bumping into day-to-day in Alum Rock. The school organized visits to Cambridge University. They took them on camping trips. They visited the Houses of Parliament in London. Some students went on a week long trip on a sailboat with kids from all over, including a bunch of white kids.

Former Student 2

We weren't used to mingling with people who were not Pakistani. So they were exposing us to you guys, OK?

Brian Reed

You're looking at me?

Former Student 2

This is what they were preparing us for.

Hamza Syed

Parents clamored to get their kids into Park View. The school had a waiting list.

Tahir Alam

We were given all kinds of accolades nationally, in the press. We had officials coming in and out of our school, really. They're saying, what are you doing? You know, perhaps we can learn something. And they invited us, actually. Then why don't you support other schools?

Hamza Syed

Tahir became well regarded in education circles. And over the years, he expanded his reach beyond Park View. He was certified as an inspector for Ofsted, the agency that monitors and rates schools in Britain. The Birmingham City Council hired him to train other governors throughout the city. The national department for education even asked Tahir and his colleagues at Park View to take over two other troubled schools in East Birmingham, which they did. Tahir was invited to tea at 10 Downing Street and met Prime Minister Tony Blair. Back in Birmingham though, some people resented him.

Moz Hussain

Yeah, he had made enemies of a lot of schools in the area. He became, like, hated amongst a lot of people.

Hamza Syed

Moz Hussain, who became Park View's acting headteacher around this time, was a full supporter of Tahir's. But still, he and other former colleagues told us they wished Tahir was a bit more circumspect in the way he went around to other schools, advocating for reform. He was self-assured, blunt, and particularly unsparing when laying out for headteachers and other school leaders the way their schools were failing Muslim students.

Moz Hussain

To tell other schools, look, Park View can do it. Park View can do it. Park View can do it. Same family, same children that you got, they can do it. That's not an excuse. We used to tell Tahir off for this a lot. Stop using us as a beating stick because it's isolating us amongst other schools.

Jackie Hughes

He was actually pointing the finger and saying directly to headteachers, you're not doing a good enough job here for these kids.

Hamza Syed

Jackie Hughes used to be in charge of school improvement for the Birmingham City Council. And she says she can name headteachers that she knows Tahir made enemies with. Many of them were used to having the final word on academics. And then here was Tahir, this volunteer with no professional teaching experience, waltzing in and criticizing their work.

Jackie Hughes

I mean, actually, people would come to me and say, I can't understand why you'd give Tahir the time of day. He's a terrible man. He said to me, blah, blah, blah, blah. And they would go sounding off.

Hamza Syed

Colleagues and friends warned Tahir, you might want to consider softening your approach. But Tahir wasn't having it.

Tahir Alam

You have to fight for justice. Justice is not going to be handed to you on the plate. You have to make space for yourself. So the fact that some people may not be OK with that is a different-- is irrelevant to me. That's their problem.

Hamza Syed

In 2012, Park View received the ultimate validation. In what was probably its proudest moment in Tahir's nearly 18 years there, Ofsted arrived for an inspection and deemed the school outstanding, the highest rating possible. Among the many things inspectors praised at Park View were the, quote, "wide range of opportunities for spiritual development, including voluntary Friday prayers."

In his time as chair of governors, Tahir had taken Park View from the lowest ranking, the verge of closure, to the very top. The person in charge of Ofsted, the chief inspector, said, quote, "Every school in the country should be like this."

Brian Reed

Less than two years later, on November 27, 2013, an envelope arrived on the desk of the leader of Birmingham City Council, a man named Sir Albert Bore. Inside was a cover sheet addressed to him, marked "Very Important," "Confidential."

"Mr. Bore," it said, "this letter was found when I was clearing my boss's files. And I think you should be aware that I am shocked at what your officers are doing. You have seven days to investigate this matter, after which it will be sent to a national newspaper, who I'm sure will treat it seriously. Sincerely, AN." "Anonymous," presumably.

Behind that note was the Trojan Horse letter, four poorly copied pages, shadows at the edges, instructions to destroy after reading. The letter was written as if from a collaborator of Tahir's, describing a conspiracy Tahir had been running to take over and Islamize schools by deception.

It took weeks for Tahir to learn about it. He heard rumors there was a mysterious letter making its way around Birmingham, around the city council and to headteachers in town, which named him as the orchestrator of a plot. One of Tahir's friends rushed to his house to tell him that he'd been getting a haircut over on Washwood Heath Road and, afterwards, his friend's barber had beckoned him into the back room of the shop and showed him a copy. Tahir did not know what to make of it. Finally, he got a hold of the document himself.

Tahir Alam

You know, obviously, I was thinking, what is the source of this letter? Who wrote this letter? Why was this letter written, is what's ringing in my head.

Brian Reed

The front page was missing, so there was no "Dear whoever." It just started as if it had been going on for a page or more already. And the letter ended mid-sentence too, with the phrase, "I would also like." So there's no sign-off, which meant Tahir couldn't tell exactly who it was supposed to be to or from. But whoever wrote the letter said explicitly, "Tahir and I."

Tahir Alam

It's supposed to be from somebody who knows me well in Birmingham. And he's talking to somebody in Bradford.

Brian Reed

Another British city that's home to a lot of Muslims.

Tahir Alam

He's talking about Tahir, what he's done here, we can do it over there.

Brian Reed

And he's your friend or your associate. Or she, whoever.

Tahir Alam

Whoever it is, yeah.

Brian Reed

Can you keep reading just the first few paragraphs?

Tahir Alam

OK. Operation Trojan Horse has been carefully thought through and is tried and tested within Birmingham. Tahir and I will be happy to support your efforts in Bradford. This is a long-term plan and one which we are sure will lead to great success in taking over a number of schools and ensuring that they are run on the strict Islamic principles. In Birmingham, the benefits--

Brian Reed

The main tactic of Operation Trojan Horse is to target headteachers at the schools you want to take control of, to make their lives so miserable that they'll resign or else be fired. At which point, you can install your own people, who will implant Islamic extremism in the school. The author gives several examples of schools in Birmingham where Tahir and his cronies were supposedly in the middle of doing this.

"We have caused a great amount of organized disruption in Birmingham," the letter says, "and are on the way to getting rid of more headteachers and taking over their schools. While sometimes the practices we use may not seem the correct way to do things, you must remember that this is a jihad. And, as such, using all means possible to win the war is acceptable."

Brian Reed

What was your feeling or your attitude? Were you laughing at it? Were you actually kind of taking it seriously and frightened? What was your--

Tahir Alam

I wasn't laughing, actually, because I knew the serious nature of the allegations that were being made. But as far as the claims themselves were concerned, they were laughable. So I knew that there was something not right about what was going on here.

Brian Reed

Tahir contacted the Birmingham City Council, where the letter was first sent. He'd done training for them for years.

Tahir Alam

And I said, look, I work for you. And this letter apparently is going around claiming certain things. And I'm surprised that you haven't spoken to me to at least to get my view on the matter. At least ask me to explain, or if I know anything, or whatever, or something.

And the gentleman there, actually, from the city council, he said, Mr. Alam, to be very honest with you, we don't think anything of the letter. We think it's a completely bogus hoax letter. And we don't believe there is any truth in it. And therefore we didn't take any action. We didn't do anything with it.

Brian Reed

Did you feel reassured by that?

Tahir Alam

Not really, no, because then the letter began to be printed in the national media as well.

Hamza Syed

Someone leaked the letter to The Sunday Times of London. And from there, it became a frenzy. One story turned to two, turned to dozens. In the Daily Mail, The Telegraph, The Spectator, Sky TV, many of them giving credence to the letter, saying that extremists like Tahir had allegedly been infiltrating UK schools for years. Reporters camped outside Park View. They stalked Tahir down the street--

Reporter 1

We tried to put these allegations to the Academy's Chair of Governors, but Tahir Alam--

Hamza Syed

--turned up at his house.

Tahir Alam

Hello.

Reporter 2

Hello, Mr. Alam? Mr. Alam.

[DOOR SHUTS]

Hello.

Hamza Syed

The government kicked into gear too. Investigators swarmed Park View. Ofsted, the school inspector, arrived for two surprise inspections.

Tahir Alam

And then we had the education funding agency investigation, which was about 10 days, I think. They were in there for 10 days. And as soon as they left, we had PWC--

Hamza Syed

PricewaterhouseCoopers, a big outside auditing firm.

Tahir Alam

--looking into the financial affairs of the school. So then we had them for five weeks in the school, as well. I said, what are you looking for? I said, what are you looking for? You've been here three weeks. You must have a family.

[LAUGHTER]

Brian Reed

There was more. The Secretary of State for Education called in England's former counterterror chief from Scotland Yard, a man named Peter Clarke. And the Birmingham City Council appointed its own special investigator. And they scrutinized Park View along with 20-some-odd other schools in Muslim neighborhoods.

In the middle of the melee, some politicians and journalists were saying that the letter itself was likely a hoax. There was some obvious factual inaccuracies. Yet the government believed it still warranted this action. Honestly, I don't think any authority explained this logic with much clarity at the time.

But my understanding of how the thinking went is that, even if the letter itself wasn't an actual communiqué between two real-life conspirators, it could still be pointing at a real problem. Even if it was fiction, the thinking went, the letter could have been fabricated by someone who had legitimate concerns about Muslim extremists scheming and wielding influence in schools. And maybe the letter was their creative way of raising an alarm.

So rather than look into who wrote the letter and why, instead, the government put out general public calls for information about these schools. And people started coming forward, mostly anonymously, with complaints. Again, investigators found no evidence of radicalization, no evidence of violent extremism, and no plot. What emerged instead was a kind of grab bag of Islam-adjacent allegations.

Many of the same things authorities had celebrated up to that point, but apparently now were seeing in a different light. Like, these educators weren't merely allowing students to pray. They were pressuring them to pray. They weren't innocently recruiting Brown Muslim staff. They were hiring their buddies who thought the same way as they did, and possibly discriminating against non-Muslim candidates in the process.

School governors, including Tahir, they weren't holding headteachers to a high standard. They were pressuring them, harassing them, and exercising more power than a governor was supposed to. Investigators also said they'd found instances of intolerance towards LGBTQ people and unequal treatment of women and girls. They said Park View had held assemblies and invited speakers with anti-Western views. And that Tahir and people aligned with him allegedly subscribed to, quote, "An intolerant and politicized form of extreme social conservatism that claims to represent, and ultimately seeks to control, all Muslims."

All of this, as the then Secretary of State for Education put it as she presented the findings on the Trojan Horse letter to Parliament, meant that students--

Nicky Morgan

Instead of enjoying a broadening and enriching experience in school, young people are having their horizons narrowed and are being denied the opportunity to flourish in a modern, multicultural Britain.

Tahir Alam

It is for this reason, and with a deep sense of injustice and sadness, that today we are announcing our intention to resign our positions at Park View Educational Trust and allow new members to assume responsibility with the--

Brian Reed

After months of scrutiny, in early July, 2014, Tahir, looking tired and stressed, stood at a lectern outside Park View's gates and resigned. Tahir told us he and the other Park View governors only agreed to do that because the Department for Education promised that the head teacher and other on-the-ground leadership of the school would be kept in place.

Tahir Alam

But as soon as school opened in September, all of those people were suspended. All the leadership was basically sacked. Ruthlessly, they went about it destroying their careers, destroying their reputations. And they did that systematically. We had worked for 10, 15 years, really, to build this school. They destroyed it within months.

Brian Reed

The government renamed the school. It's no longer Park View. It also notified nearly every teacher and governor you just heard from, Tahir included, that it was bringing proceedings to ban them from education for the rest of their lives.

In the years since, student achievement has plummeted at the school formerly known as Park View. From more than 70% passing to, in recent years, from the low-40% to mid-50% range.

Hamza Syed

So that's the story Tahir told us, that first meeting, in his makeshift tutoring room, that this letter, which was never fully investigated, that described a plot called Operation Trojan Horse, which was never found to have existed, inspired all of this, the ruining of careers and an educational movement, the fear-mongering headlines against Muslims that continue to this day, the government instituting policies that encourage us to spy more brazenly on each other. We'd been talking with Tahir for a couple of hours by this point.

Brian Reed

What time is it? I know you need to leave at some point. I don't want--

Tahir Alam

I mean, I'm-- I have to go to Friday prayer now. So, 1 o'clock, I'm there really.

Brian Reed

I understand it's a lot to talk. So if you wanted to--

Tahir Alam

There's a lot to-- no, no, I don't get tired of talking these things really. I mean, you probably could tell. Obviously, when I talk about that, you know, you begin to relive it, isn't it? And I have to say that it does sadden me, actually, as to what has been lost for the children, for the community, the irreparable damage that has been done for absolutely no reason whatsoever. So, anyway, can I get you guys some tea or something?

Hamza Syed

At that event I went to, where we all got redirected to the wedding hall, one of the speakers, a columnist named Peter Oborne, put it well. He said Operation Trojan Horse has become a social fact in Britain. That, even though within weeks that the Trojan Horse started hitting the news, people acknowledged it was probably a hoax, that's never seemed to matter. Whether Muslims in Birmingham were conspiring or not doesn't matter. The intimation that they were has persevered, to the extent that a prime minister's former chief of staff was outraged that some people in the community center would dare to say otherwise.

But we don't need to settle for a social fact because there are actual facts. Why, up to this point, has no one cared about who wrote this letter and where this letter came from?

Tahir Alam

Well, that's my question.

Hamza Syed

(LAUGHING) That's my question.

Tahir Alam

This is what I've been arguing. This is why I went to the police to see what they could do. This is what I wrote in my letter to the Birmingham City Council, that you need to get to the bottom of who wrote the letter. This is what I wrote to the Department of Education as well. You need to get to the bottom of the letter, who wrote the letter. Because that will then unravel why the letter was written. You see? So this is what I have been arguing.

But Department of Education is not interested. The police are not interested. The Birmingham City Council is not interested in answering that question.

Hamza Syed

Why?

Tahir Alam

Because they have used this letter. And on this hoax they have built so much policy. Do you think now they want to launch an investigation into the letter to have it proven that it was written for completely different reasons? Yeah? How would that make them look like? A bunch of monkeys.

Hamza Syed

As I've been saying, if you could just find out who wrote that letter and why, that's the only thing that might change Britain's understanding of Operation Trojan Horse.

Tahir Alam

But whoever wrote the letter, they knew me, I think. And I like to think that I know them too.

Hamza Syed

Does that mean you think--

Tahir Alam

I have a strong hunch as to who wrote the letter. I strongly believe that I know who wrote the letter. And I strongly believe that I know the why the letter was written as well.

Brian Reed

So you think you know the who and the motive.

Tahir Alam

Yes.

Hamza Syed

That's next on The Trojan Horse Affair.

Ira Glass

So that is part 1 of The Trojan Horse Affair. You can listen to all eight installments right now, wherever you get your podcasts.

[MUSIC - "FROGGY" BY JAYKAE AND DAPZ ON THE MAP]

Credits

Ira Glass

The Trojan Horse Affair is produced by Brian Reed and Hamza Syed, with Rebecca Laks. It's edited by Sarah Koenig with help from Julie Snyder, Neil Drumming, and me. Contributing editor is Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi. Fact checkers, Marika Cronnolly and Ben Phelan. The episode was mixed by Steven Jackson. Audio was provided by NBC, Getty Images. Bim Adewunmi, and Mike Comite help put their show into an episode of our show.

Special thanks today to Richard Danbury, Kimberly Henderson, The Barclay Agency, Kenneth Pomeranz, Greg Clark, and John Holmwood.

The Trojan Horse Affair is made by Serial Productions and The New York Times. Our website, ThisAmericanLife.org. This American Life is delivered to public radio stations by PRX, the Public Radio Exchange. Thanks as always to our program's co-founder, Mr. Torey Malatia.

Sure, you always love Shakespeare, the Beatles, the BBC, Harry Potter. But it was Fleabag that put him over the top.

Hamza Syed

So, from that point onwards, I've started calling myself British. I was just like, well, I'm British. I own this country.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.

[MUSIC - "FROGGY" BY JAYKAE AND DAPZ ON THE MAP]

(SINGING) We know, we know. We know, we know.